$12.95

Civil War: 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Commander Robert G. Shaw Letters & Papers

Civil War: 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

Commander Robert G. Shaw - Letters & Papers

1,104 pages of letters written by, and papers related to Colonel Robert G. Shaw, commander of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, one of the first official African-American units in the United States during the Civil War, copied from material held by the Houghton Library.

Robert Gould Shaw (October 10, 1837 – July 18, 1863) was an American military officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. As Colonel, he commanded the all-black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. The 54th was created under the order of Massachusetts Governor John Andrew in 1863. Shaw was killed in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, near Charleston, South Carolina.

Shaw is most widely known as the principal character in the 1989 film Glory, portrayed by the actor Matthew Broderick.

In the introduction to his book, "Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw," Russell Duncan described Shaw's letters as conveying, "the change wrought by battlefield casualties, camp life, commitment, and homesickness upon the sensibilities of youth. His soldiering experience was as common as it was distinctive." Duncan concluded his initial description of Shaw's letters by writing, "His prose is often eloquent, always articulate, intensely informative, amusing, heart wrenching, and provocative more than a century after he described himself in letters to his family and friends. As interlopers to words never meant for us to ponder, we can enjoy him and gain insight into his times and into ours."

Most of the documents in this collection are letters written by Robert Gould Shaw to his family. Most of the letters, ninety-eight, are addressed to his mother, and thirty-one were written to his father. The collection also includes letters to his sisters and brothers-in-law. The majority of Shaw's letters were written during the Civil War. A few of the earliest letters are from before he joined the army, written while a student at Harvard or during his travels in Europe. A section of the material is made up of correspondence and genealogical research of the Barlow family, one of Shaw's sisters married Francis Channing Barlow. Also included are the contents of a box of notes created by Louisa Barlow Jay, for an unfinished Robert Shaw biography.

Early in the Civil War, Shaw joined the 7th New York Militia and in April 1861 marched with it to the defense of Washington, D.C. In May 1861 he joined the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry as a second lieutenant, with which he fought in the First battle of Winchester, the Battles of Cedar Mountain, and Antietam.

Shaw was approached by his father while in camp in late 1862 with the offer to take command of a new all-Black Regiment. At first he declined the offer, but later accepted the position. Shaw's letters clearly state that he was dubious about a free black unit succeeding, but the dedication of his men deeply impressed him, and he grew to respect them as soldiers.

On learning that black soldiers would receive less pay than whites, he inspired his unit to conduct a boycott until this inequality was rectified. After Shaw's death at Fort Wagner, Colonel Edward Needles Hallowell took up the fight to get back full pay for African-American troops. The enlisted men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and the 55th refused pay until Congress granted them full back in August 1863.

The 54th Regiment was sent to Charleston, South Carolina to take part in the operations against the Confederates stationed there. On July 18, 1863, along with two brigades of white troops, the 54th assaulted Confederate Battery Wagner. Shaw mounted a parapet and urged his men forward. According to the Colors Sergeant of the 54th, he was shot and killed while trying to lead the unit forward and fell on the outside of the fort. The Confederates buried him in a mass grave with many of his men, an act they intended as an insult.

Following the battle, commanding Confederate General Johnson Hagood returned the bodies of the other Union officers who had died, but left Shaw's where it was. Hagood informed a captured Union surgeon that "had he been in command of white troops, I should have given him an honorable burial; as it is, I shall bury him in the common trench with the n----rs that fell with him." Although the gesture was intended as an insult, it came to be seen as an honor by Shaw's friends and family that he was buried with his soldiers.

Highlights from the collection include:

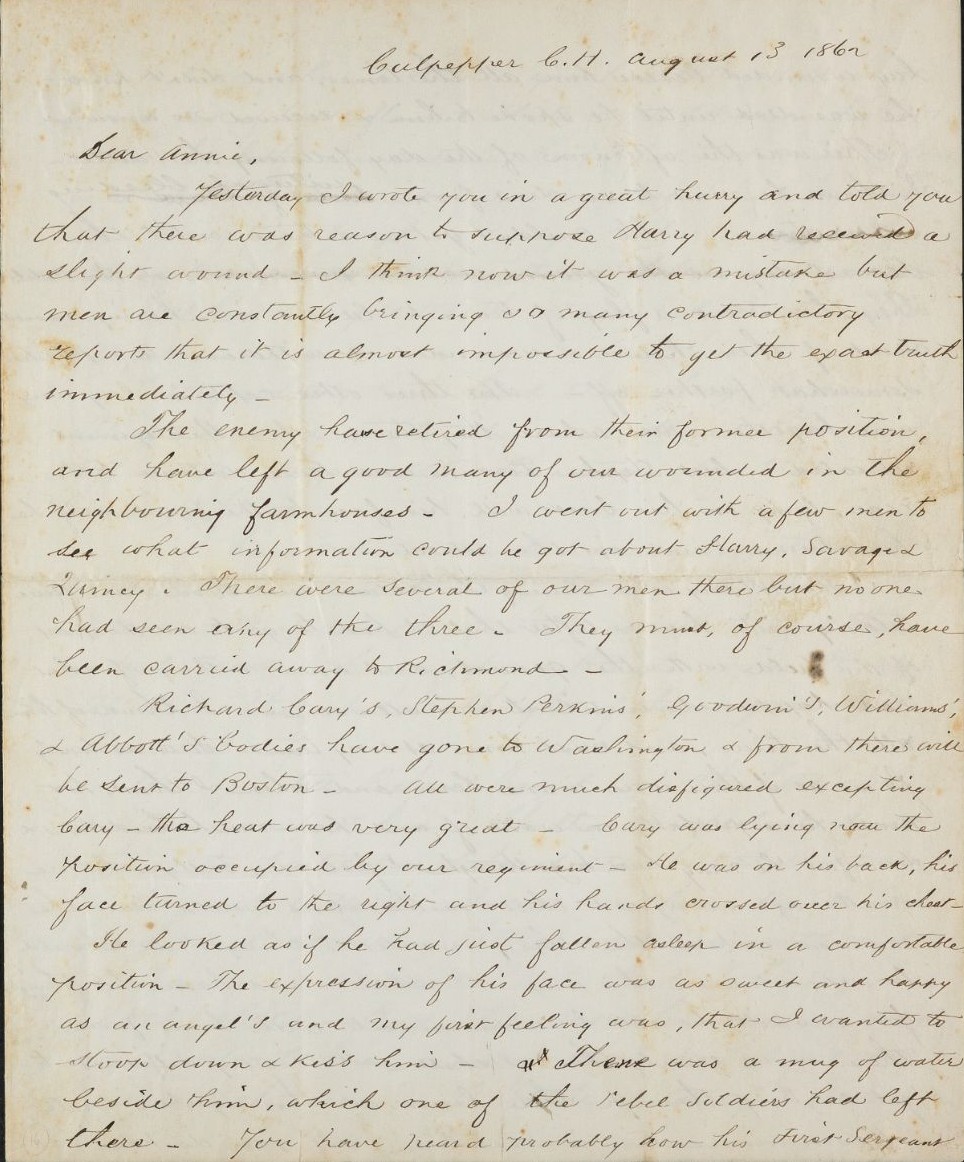

1862-08-13

Shaw writes to his cousin Annie Russell about the scene of the aftermath at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, where he served as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry.

Page 1 of 4, third and fourth paragraph: "Richard Gary's, Stephen Perkins', Goodwin's, William's, & Abbott's bodies have gone to Washington & from there will be sent to Boston. All were much disfigured excepting Gary - the heat was very great. Cary was lying near the position occupied by our regiment - He was on his back, his face turned to the right and his hands crossed over his chest.

He looked as if he had just fallen asleep in a comfortable position. The

expression of his face was as sweet and happy as an angel's and my first feeling was, that I wanted to stoop down & kiss him..."

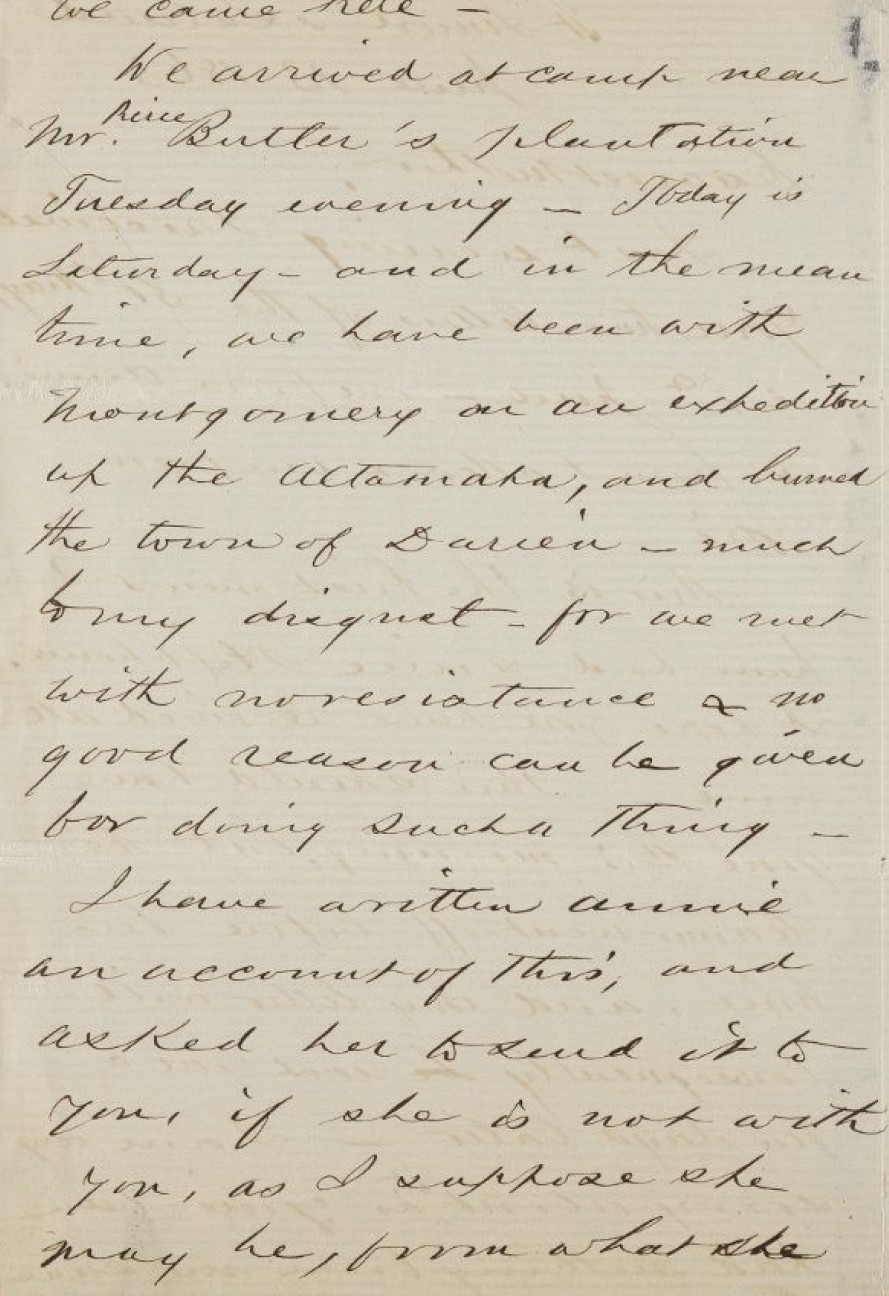

1863-06-13

In a letter to his mother dated June 13, 1863, Shaw writes about his displeasure at being ordered to participate in the burning of Darien, Georgia.

"We arrived at camp near Mr. Pierce Butler's plantation Tuesday evening - Today is Saturday — and in the mean time, we have been with Montgomery on an expedition up the Altamaha, and burned the town of Darien - much to my disgust - for we met with no resistance & no good reason can be given for doing such a thing."

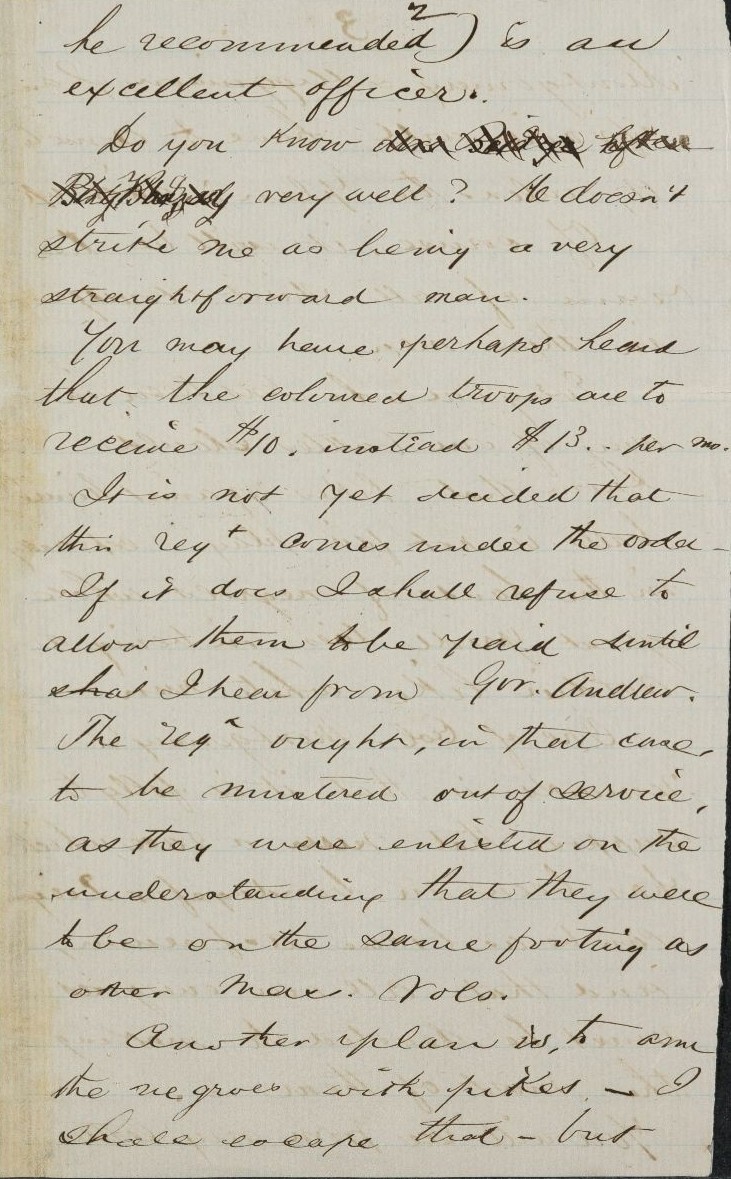

1863-07-01

Second page of a letter from Shaw to his father dated July 1, 1863. Shaw mentions the pay disparity suffered by the soldiers under his command, Shaw wrote:

"You may have perhaps heard that the coloured troops are to receive $10 instead $13 per mo. It is not yet decided that this regt comes under the order. If it does I shall refuse to allow them to be paid until I hear from Gov. Andrew. The regt ought, in that case, to be mustered out of service, as they were enlisted on the understanding that they were to be on the same footing as other Mass. Vols."

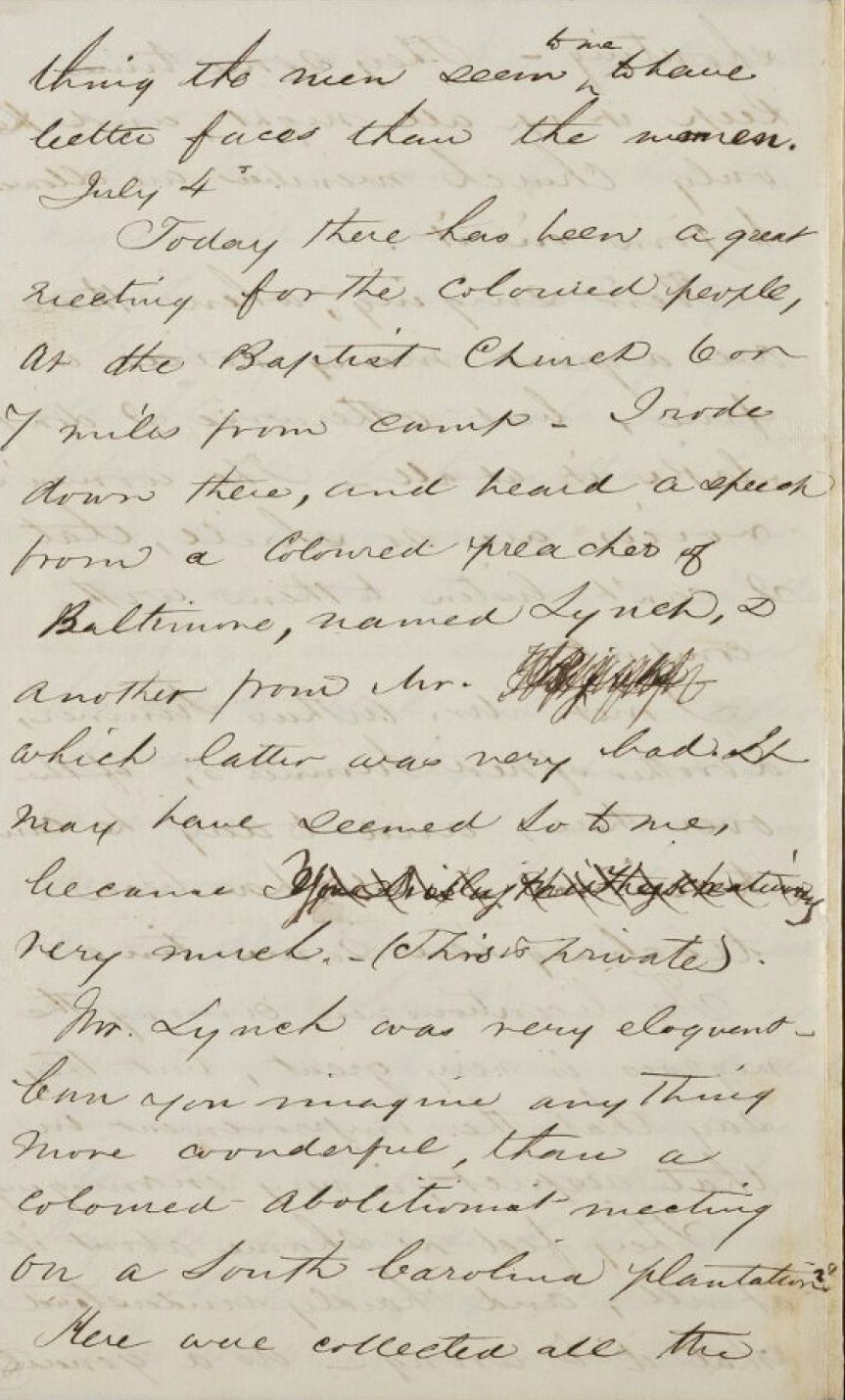

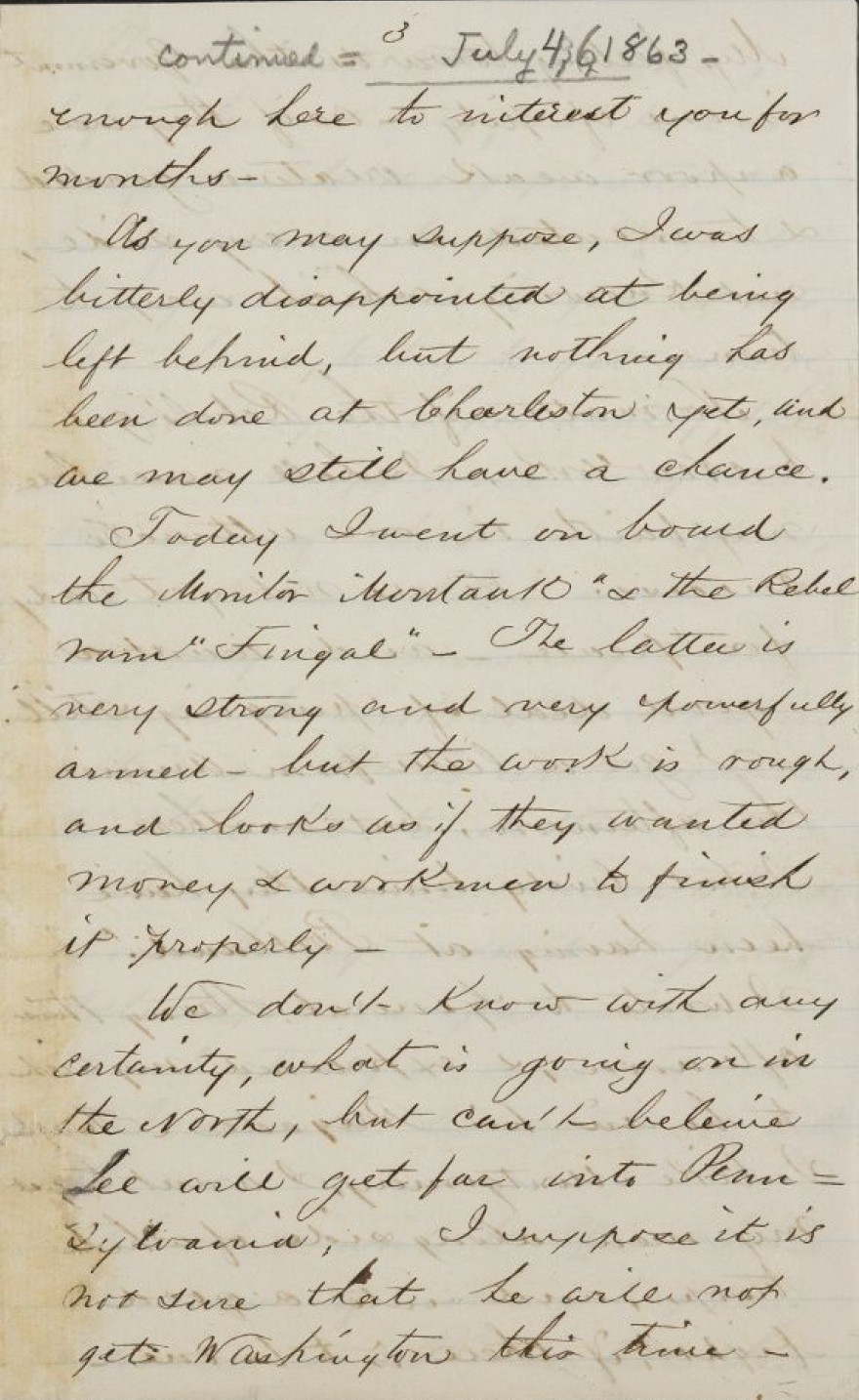

1863-07-04

The last letter written by Shaw in this collection.

In a twelve page letter to his mother written from July 3 to July 6 while on St. Helena's Island, Shaw gives an account of the African-American population on the island. The island came under Union control on November 7, 1861, and remained so until after the war. Shaw wrote about meeting Nat Turner's brother, attending the July 4th Independence Day "praise meeting" which consisted of a reading of the Declaration of Independence, singing and prayers, and a marriage ceremony performed at an African-American Baptist church.

Shaw wrote:

"Mr. Lynch was very eloquent. Can you imagine anything more wonderful than a coloured - Abolitionist meeting on a South Carolina plantation? Here were collected all the freed slaves on this Island listening to the most ultra abolition speeches, that could be made; while two years ago, their masters were still here, the lords of the soil & of them. Now they all own a little themselves, go to school, to church, and work for wages. It is the most extraordinary change. Such things oblige a man to believe that God isn't very far off."

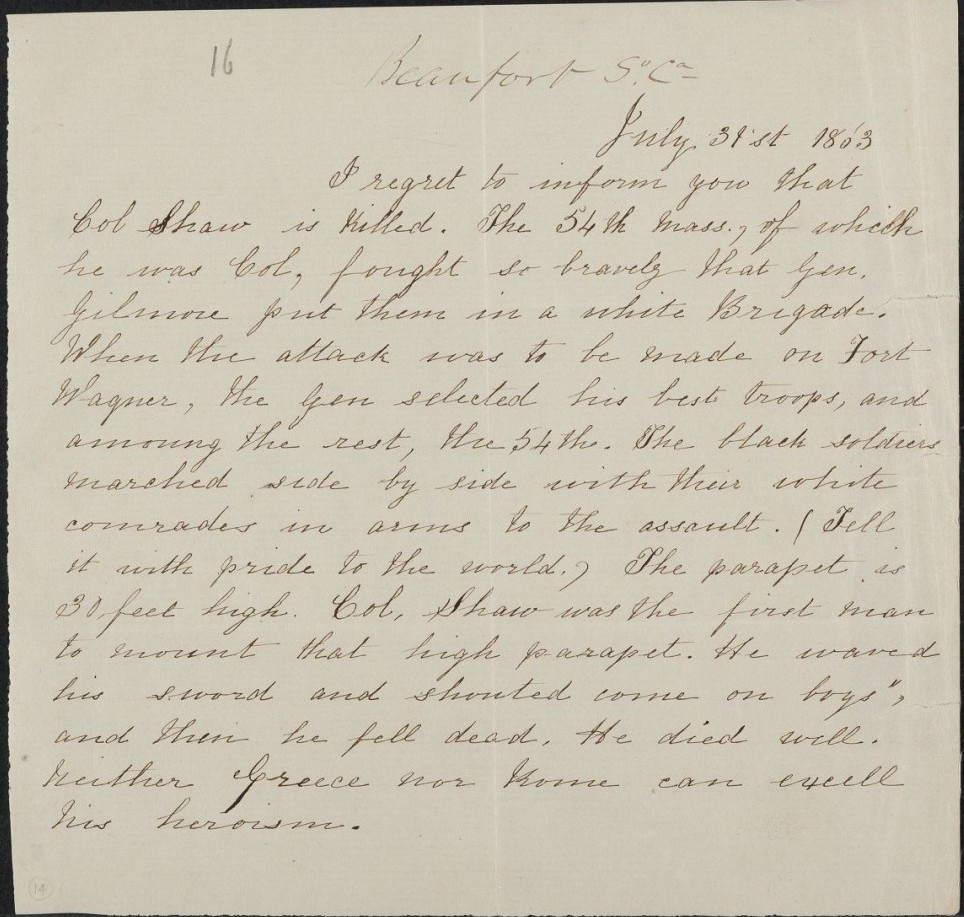

1863-07-31

A letter sent to the Shaw family, possibly by the Regiment's surgeon, confirming the death of Shaw.