Starting from:

$0

Home

Civil War

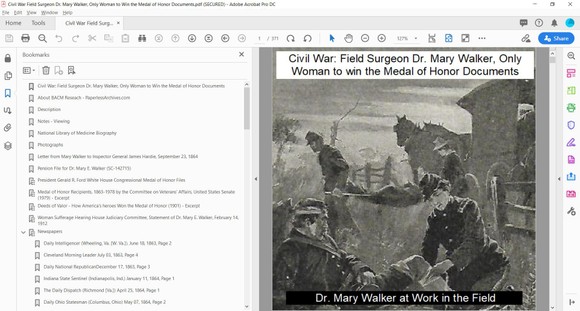

Civil War: Field Surgeon Dr. Mary Walker, Only Woman to win the Medal of Honor Documents

Civil War: Field Surgeon Dr. Mary Walker, Only Woman to win the Medal of Honor Documents

Civil War: Field Surgeon Dr. Mary Walker, Only Woman to win the Medal of Honor Documents

Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919) a doctor, suffragist, Civil War surgeon, suspected spy, prisoner of war and the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor was born in 1832 in Oswego, New York, to an abolitionist family. Her progressive parents encouraged their seven children to be "free thinkers," they were raised to question everything. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College with a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1855. Following her graduation, she married her fellow medical student, Albert Miller, and they set up a joint practice in Rome, New York. The practice failed, ostensibly because the public would not accept a female doctor. She refused to agree to "obey" Albert in her wedding vows, kept her last name, and wore a short skirt and trousers, instead of a traditional wedding dress; they later divorced. In 1860, she briefly attended Bowen Collegiate Institute in Hopkinton, Iowa. She was suspended from the school for refusing to resign from the school's otherwise all-male debate team.

Civil War Surgeon

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the Union Army did not commission women as surgeons, only nurses. Wanting to serve her country, but still wanting to work to her full capacity, Walker volunteered as an unpaid surgeon. She began working as an assistant surgeon at the Indiana Hospital, an improvised hospital inside the U.S. Patent Office in Washington DC. Throughout the War, she wore men's clothing, arguing that doing so made her job easier. She served at the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), July 21, 1861. In 1862 she treated the wounded at various field hospitals throughout Virginia. In 1862, she worked as a field surgeon near the front lines at Fredericksburg and Chattanooga.

In September 1862, Walker wrote to the War Department requesting employment as a spy, but her proposal was declined.

While serving as an assistant surgeon with the 52nd Ohio Infantry, she routinely crossed the lines to treat civilians. On one such foray in 1864, she was detained by Confederate troops and arrested for spying just after she finished helping a Confederate doctor perform an amputation. While imprisoned, she continued to refuse to wear traditionally feminine clothing. After spending four months at the notorious Castle Thunder prison near Richmond, Virginia, Dr. Walker was freed in April of 1864 and released in a prisoner swap. It wasn’t until later that October that she became a paid contracted private physician with the Ohio 52nd Infantry with a salary of $100 a month. She ended this contract in June of 1865.

After the war, Dr. Walker was awarded a disability pension for an injury she suffered while in Castle Thunder prison. On January 24, 1866, she was awarded the Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service by the Executive Order of President Andrew Johnson, based on the recommendation of Major Generals Sherman and Thomas.

In 1917, Congress requested a review of cases of Medal of Honor recipients and rescinded 912 awards, including Dr. Mary Walker’s. It was restored to her posthumously in 1977 at the behest of the Army Board of Correction of Military Records.

The remainder of her life was devoted to the medical profession and the advancement of women’s rights.

Dress Freedom

In addition to her many accomplishments as a surgeon, Dr. Walker was a pioneer in women’s dress reform. While working on the family farm when she was growing up, Walker often wore trousers and shirts because they were more comfortable. Dr. Walker opposed long skirts and petticoats, particularly due to the dust and dirt they spread as women walked about, so she experimented with shorter skirts layered with trousers and often skipped the skirts entirely in favor of wearing pants. By the 1860s, while a surgeon during the Civil War, Dr. Walker typically wore a knee-length dress with trousers underneath.

Her choice of profession and dress marked her for harassment and ridicule her whole life. In 1870, while she was in New Orleans, she was arrested because she was because of her non-traditional dress. Dr. Walker was released from custody only after she was recognized by officers of the court. She was frequently arrested for wearing men's clothes, including her signature top hat. She responded to those who criticized her choices, "I don't wear men's clothes, I wear my own clothes."

Suffragist

Dr. Walker was active in the fight for woman’s suffrage, and tried to register to vote in 1871, but was denied. She was among the early advocates for women's suffrage who argued that the Constitution had already granted women the right to vote, and that all that was required was enabling legislation from Congress. In 1912 and 1914, she testified in front of the US House of Representatives in support of women's suffrage. She became increasingly distanced from the mainstream fight for suffrage as people began to argue instead for a constitutional amendment recognizing women's right to vote.

In her later years, Dr. Walker opened her home to those who were also ostracized, harassed, and arrested for not conforming to traditional ideas of how people should dress. Dr. Mary Walker died at her home on February 21, 1919. She was buried in a black suit at Rural Cemetery in Oswego, New York.

This collection includes:

Letter from Mary Walker to General James Hardie, September 23, 1864

A letter written by Walker describing her meeting with President Lincoln and the nature of her service during the Civil War.

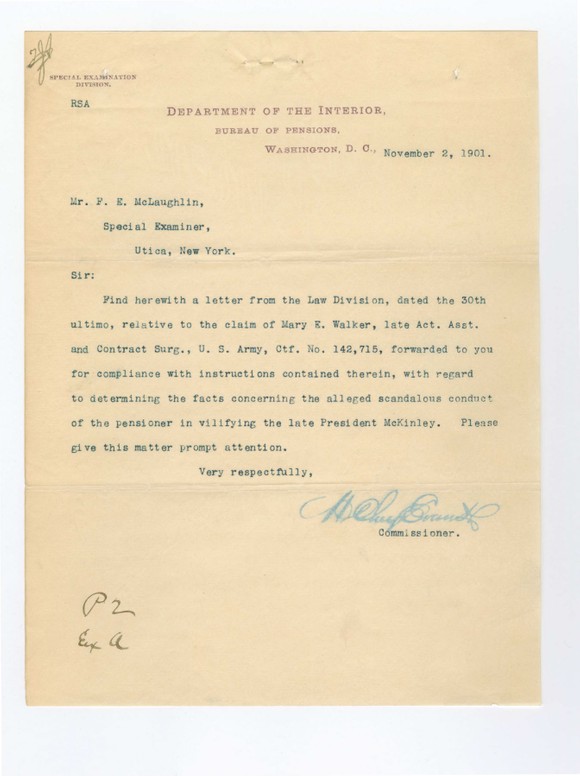

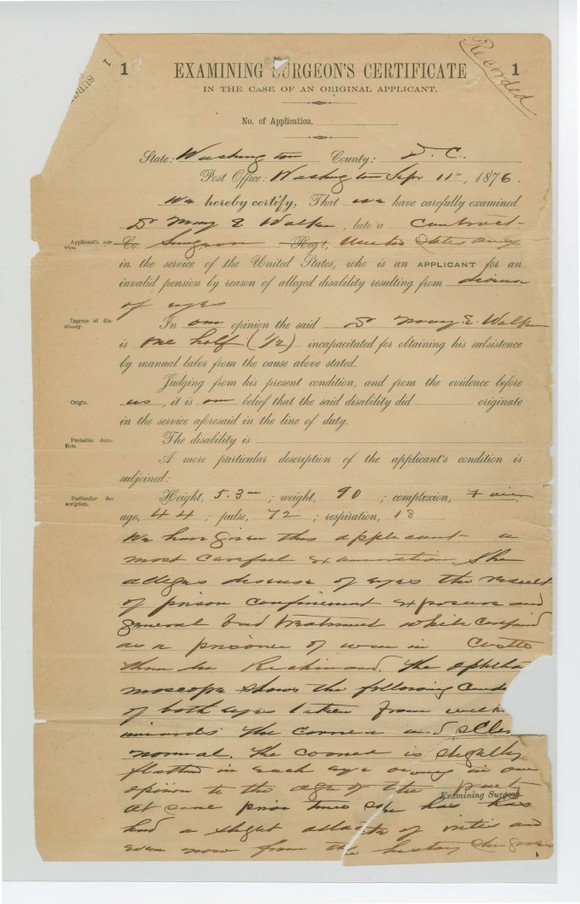

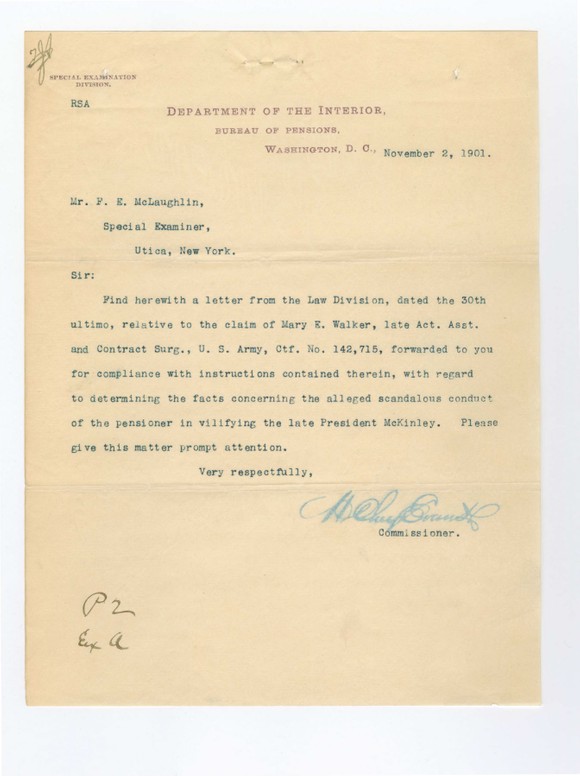

Department of the Interior Bureau of Pension File

Dr. Mary Walker's Veteran’s pension case file. After the war, Walker was awarded a disability pension for an injury that occurred while she was a POW. She was given $8.50 a month, beginning June 13, 1865, but in 1901 that amount was raised to $20 per month. Her files show that someone contacted the pension board with an accusation that Walker expressed pleasure that President McKinley was assassinated.

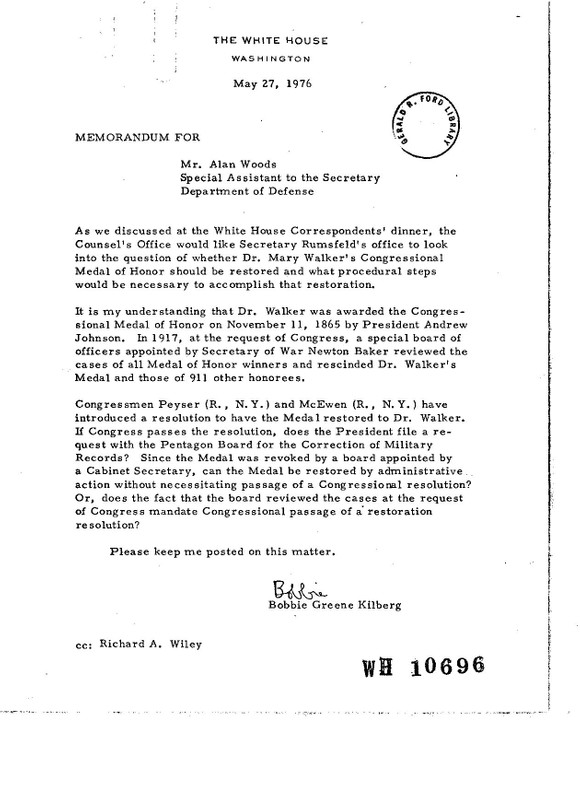

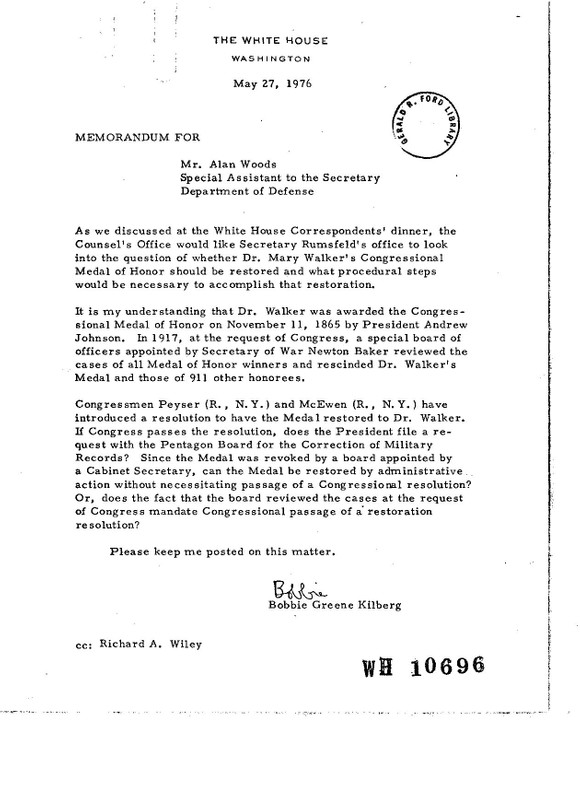

President Gerald R. Ford White House Congressional Medal of Honor Files

Documents from the Bobbie Greene Kilberg Files, at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, related to the consideration of whether Dr. Mary Walker's Congressional Medal of Honor should be restored.

Medal of Honor Recipients, 1863-1978 by the Committee on Veterans' Affairs, United States Senate (1979) - Excerpt

Entry containing a summation bout Dr. Walker's Medal of Honor and its restoration.

Newspapers

75 full page newspaper sheets from across the United States, dating from 1863 to 1922, carrying articles about Walker. An article in the December 17, 1863 edition of Washington DC's Daily National Republican covers a homeless shelter for women Walker opened in DC. A reprint of a letter by Walker to the editor of the Richmond Display, while she was a prisoner of war in a Confederate prison, complaining that the paper described her as "dressed in male attire." She corrected the newspaper writing that what she wears are "bloomers" or "reform dress." The Salt Lake Herald on December 27, 1882, while she was sick predicted Walker's death would be soon and ran a semi-obituary. The newspaper was 37 years too early. Chicago's The Day Book on March 30, 1912, carries an article, in which Dr. Walker claims she passed on a chance to marry former President Chester Arthur.

Book - Hit by Dr. Mary E. Walker (1871)

Written by Dr. Walker a few years after the Civil War. Walker in a series of essays addresses love and marriage, dress reform, tobacco, temperance, woman's franchise, divorce, labor and religion.

Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919) a doctor, suffragist, Civil War surgeon, suspected spy, prisoner of war and the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor was born in 1832 in Oswego, New York, to an abolitionist family. Her progressive parents encouraged their seven children to be "free thinkers," they were raised to question everything. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College with a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1855. Following her graduation, she married her fellow medical student, Albert Miller, and they set up a joint practice in Rome, New York. The practice failed, ostensibly because the public would not accept a female doctor. She refused to agree to "obey" Albert in her wedding vows, kept her last name, and wore a short skirt and trousers, instead of a traditional wedding dress; they later divorced. In 1860, she briefly attended Bowen Collegiate Institute in Hopkinton, Iowa. She was suspended from the school for refusing to resign from the school's otherwise all-male debate team.

Civil War Surgeon

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the Union Army did not commission women as surgeons, only nurses. Wanting to serve her country, but still wanting to work to her full capacity, Walker volunteered as an unpaid surgeon. She began working as an assistant surgeon at the Indiana Hospital, an improvised hospital inside the U.S. Patent Office in Washington DC. Throughout the War, she wore men's clothing, arguing that doing so made her job easier. She served at the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), July 21, 1861. In 1862 she treated the wounded at various field hospitals throughout Virginia. In 1862, she worked as a field surgeon near the front lines at Fredericksburg and Chattanooga.

In September 1862, Walker wrote to the War Department requesting employment as a spy, but her proposal was declined.

While serving as an assistant surgeon with the 52nd Ohio Infantry, she routinely crossed the lines to treat civilians. On one such foray in 1864, she was detained by Confederate troops and arrested for spying just after she finished helping a Confederate doctor perform an amputation. While imprisoned, she continued to refuse to wear traditionally feminine clothing. After spending four months at the notorious Castle Thunder prison near Richmond, Virginia, Dr. Walker was freed in April of 1864 and released in a prisoner swap. It wasn’t until later that October that she became a paid contracted private physician with the Ohio 52nd Infantry with a salary of $100 a month. She ended this contract in June of 1865.

After the war, Dr. Walker was awarded a disability pension for an injury she suffered while in Castle Thunder prison. On January 24, 1866, she was awarded the Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service by the Executive Order of President Andrew Johnson, based on the recommendation of Major Generals Sherman and Thomas.

In 1917, Congress requested a review of cases of Medal of Honor recipients and rescinded 912 awards, including Dr. Mary Walker’s. It was restored to her posthumously in 1977 at the behest of the Army Board of Correction of Military Records.

The remainder of her life was devoted to the medical profession and the advancement of women’s rights.

Dress Freedom

In addition to her many accomplishments as a surgeon, Dr. Walker was a pioneer in women’s dress reform. While working on the family farm when she was growing up, Walker often wore trousers and shirts because they were more comfortable. Dr. Walker opposed long skirts and petticoats, particularly due to the dust and dirt they spread as women walked about, so she experimented with shorter skirts layered with trousers and often skipped the skirts entirely in favor of wearing pants. By the 1860s, while a surgeon during the Civil War, Dr. Walker typically wore a knee-length dress with trousers underneath.

Her choice of profession and dress marked her for harassment and ridicule her whole life. In 1870, while she was in New Orleans, she was arrested because she was because of her non-traditional dress. Dr. Walker was released from custody only after she was recognized by officers of the court. She was frequently arrested for wearing men's clothes, including her signature top hat. She responded to those who criticized her choices, "I don't wear men's clothes, I wear my own clothes."

Suffragist

Dr. Walker was active in the fight for woman’s suffrage, and tried to register to vote in 1871, but was denied. She was among the early advocates for women's suffrage who argued that the Constitution had already granted women the right to vote, and that all that was required was enabling legislation from Congress. In 1912 and 1914, she testified in front of the US House of Representatives in support of women's suffrage. She became increasingly distanced from the mainstream fight for suffrage as people began to argue instead for a constitutional amendment recognizing women's right to vote.

In her later years, Dr. Walker opened her home to those who were also ostracized, harassed, and arrested for not conforming to traditional ideas of how people should dress. Dr. Mary Walker died at her home on February 21, 1919. She was buried in a black suit at Rural Cemetery in Oswego, New York.

This collection includes:

Letter from Mary Walker to General James Hardie, September 23, 1864

A letter written by Walker describing her meeting with President Lincoln and the nature of her service during the Civil War.

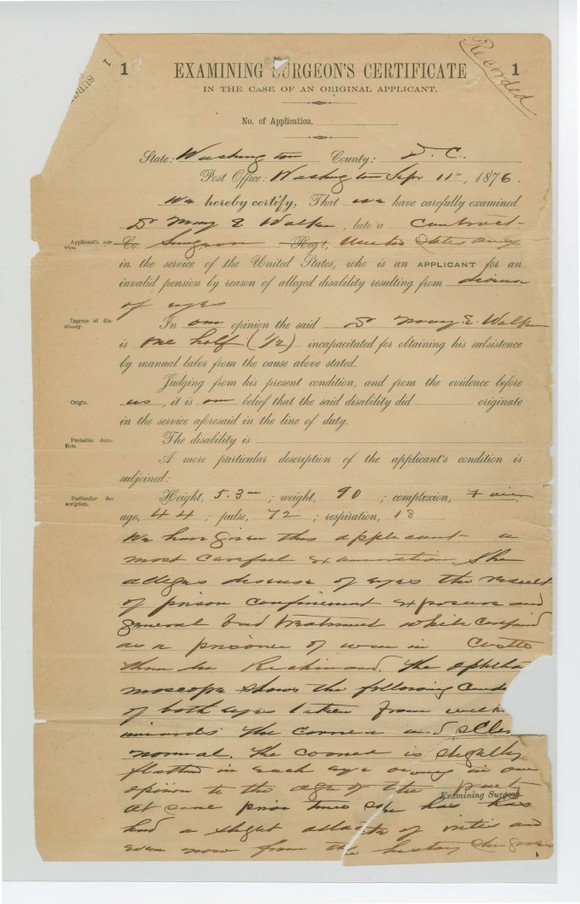

Department of the Interior Bureau of Pension File

Dr. Mary Walker's Veteran’s pension case file. After the war, Walker was awarded a disability pension for an injury that occurred while she was a POW. She was given $8.50 a month, beginning June 13, 1865, but in 1901 that amount was raised to $20 per month. Her files show that someone contacted the pension board with an accusation that Walker expressed pleasure that President McKinley was assassinated.

President Gerald R. Ford White House Congressional Medal of Honor Files

Documents from the Bobbie Greene Kilberg Files, at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, related to the consideration of whether Dr. Mary Walker's Congressional Medal of Honor should be restored.

Medal of Honor Recipients, 1863-1978 by the Committee on Veterans' Affairs, United States Senate (1979) - Excerpt

Entry containing a summation bout Dr. Walker's Medal of Honor and its restoration.

Newspapers

75 full page newspaper sheets from across the United States, dating from 1863 to 1922, carrying articles about Walker. An article in the December 17, 1863 edition of Washington DC's Daily National Republican covers a homeless shelter for women Walker opened in DC. A reprint of a letter by Walker to the editor of the Richmond Display, while she was a prisoner of war in a Confederate prison, complaining that the paper described her as "dressed in male attire." She corrected the newspaper writing that what she wears are "bloomers" or "reform dress." The Salt Lake Herald on December 27, 1882, while she was sick predicted Walker's death would be soon and ran a semi-obituary. The newspaper was 37 years too early. Chicago's The Day Book on March 30, 1912, carries an article, in which Dr. Walker claims she passed on a chance to marry former President Chester Arthur.

Book - Hit by Dr. Mary E. Walker (1871)

Written by Dr. Walker a few years after the Civil War. Walker in a series of essays addresses love and marriage, dress reform, tobacco, temperance, woman's franchise, divorce, labor and religion.

1 file (117.7MB)