Starting from:

$12.95

Home

Civil War

Civil War: U.S. Surgeon General Photographs and Histories of Surgical Cases and Specimens - Download

Civil War: U.S. Surgeon General Photographs and Histories of Surgical Cases and Specimens - Download

Civil War: U.S. Surgeon General Photographs and Histories of Surgical Cases and Specimens

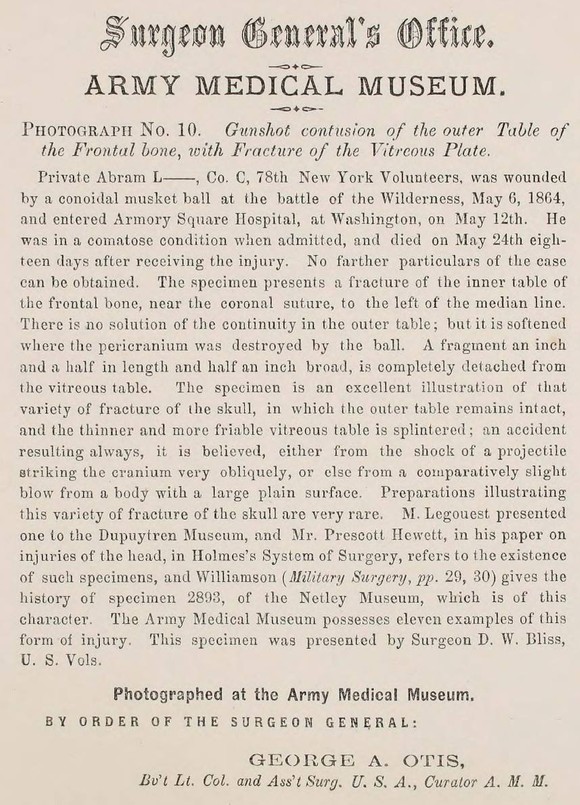

660 pages in six volumes of photos commissioned by the United States surgeon general and case summaries of injuries suffered during the Civil War.

The photographs in this collection contain graphic medical images of injuries and anatomy, which may not be suitable for all audiences. The reproductions of these volumes are unedited.

These images flout some of the romanticism often imposed on the Civil War and show the real faces, injuries, and sacrifices regularly made by Civil War fighters, both Union and Confederate.

According to the National Museum of Health and Medicine of the approximately 3 million soldiers and sailors who participated in Civil War combat approximately 618,000 died, nearly 400,000 of these deaths were due to disease. The death toll was nearly 2% of the entire population. Among the 79% of combatants who survived the war, nearly half a million returned home permanently maimed or disabled.

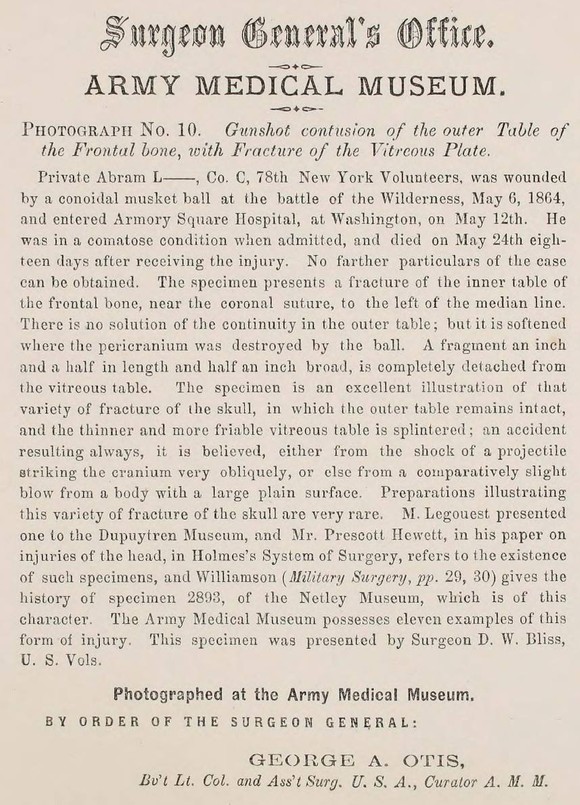

The photographs and illustrations in this collection are vivid. They starkly illustrate the traumatic effects of recently developed warfare technology of the Civil War era on the human body. The collection contains detailed case histories written by the staff of the Army Medical Museum. The entries accompany each photograph and record the names and ranks of soldiers, specific battles where the injury occurred, dates of injury, treatment narratives, and final outcomes. This material compiled in the 1860's, now provide a wealth of medical and biographical information to historians and other interested parties.

The materials in these volumes were prepared by direction of the Surgeon General's Office, by Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George A. Otis, Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A., Curator of the Army Medical Museum. Founded in 1862 by Surgeon General William Hammond of the Union Army, the Army Medical Museum was a clearinghouse for medical information collected from Union surgeons.

Surgeon General William Hammond directed medical officers in the field to collect "specimens of morbid anatomy together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" and to forward them to the newly founded museum for study. The Museum's first curator, John Brinton, visited mid-Atlantic battlefields and solicited contributions from doctors throughout the Union Army. During and after the war, Museum staff took pictures of wounded soldiers showing effects of gunshot wounds, as well as results of amputations and other surgical procedures.

Many of these anatomical specimens collected on behalf of the Army Medical Museum (now called the National Museum of Health and Medicine) by Dr. John Hill Brinton are photographed in this collection. The compilation and photography of subjects was supervised by Dr. George Alexander Otis, who succeeded Brinton as curator of the museum in 1864. William Bell, famous for his later images of the American West, served as Chief Photographer for the museum from 1865 to 1868, and photographed many of the portrait sitters and specimens himself.

This collection contains 300 case narratives, 286 photographs of patients and specimens, and 14 illustrations. The cases and specimens were chosen by museum staff from the thousands of pieces of material available at the Army Medical Museum as the most important for study.

Scope and Content

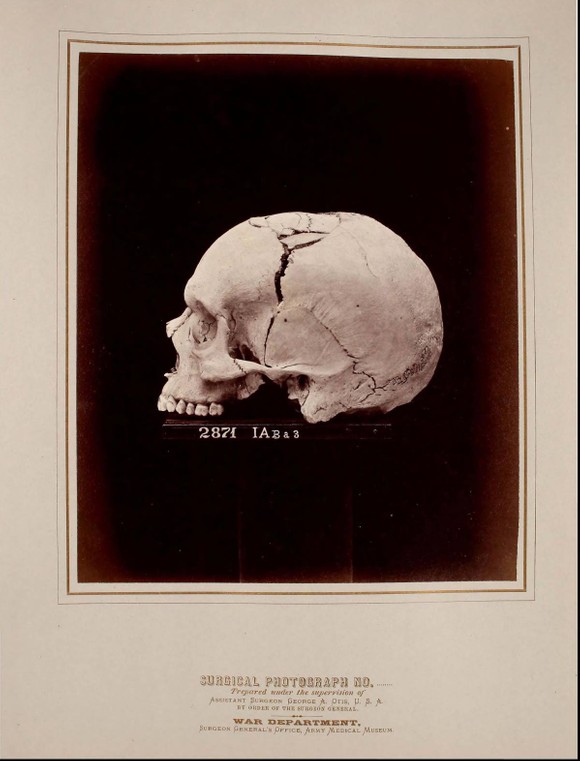

The six volumes contain mounted albumen photographic prints with accompanying case histories, Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens contains extensive visual documentation of patients who suffered traumatic wounds during and shortly after the Civil War. The majority of the subjects were soldiers, both Union and Confederate, though the later volumes in the series, compiled and published after the war, include civilian cases that were considered relevant additions to the collection. The work contains both portraiture and specimen photography, as well as a small number of photographically-reproduced drawings and paintings. The majority of specimens illustrate fractures or necrotic bone degeneration arising from shrapnel or gunshot wounds.

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate soldiers received approximately 350,000 wounds to the extremities leading to about 60,000 amputations.

Surgery in the 1860's

Before the Civil War, military medical care was the duty of the regimental surgeon and surgeons' mates. The war saw attempts to establish a centralized medical system. The availability of effective treatment for disease and injury was, by modern standards, primitive. During battles undersupplied and understaffed medical departments often worked within the limitations of battlefield hospitals just beyond the range of gunfire. Although medical personnel made every effort to treat the wounded quickly and efficiently, severely injured men often received little or no treatment for one to two days after a major engagement.

Significant changes began to occur during the Civil War, when improvements in medical science, communications and transportation made centralized casualty collection and treatment more practical. Despite the lack of both surgical experience and sanitary conditions, the survival rate among those who underwent wartime surgery was better than in previous wars. Amputation was not the only surgical recourse available. Surgeons also extracted bullets, operated on fractured skulls, reconstructed damaged facial structures, and removed sections of broken bones. According to the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Union surgeons documented nearly 250,000 wounds from bullets, shrapnel, and other missiles. Fewer than 1,000 cases were reported of wounds caused by sabers and bayonets.

Amputations

During the Civil War surgeons often found it necessary to treat arm and leg wounds by amputating. The complex wounds caused by bullets and shrapnel were often contaminated by foreign material. The dreaded minié ball tore through the flesh, splintered bone and destroyed tissue beyond repair. Fragments of bone along with dirt, torn cloth and germs caused infections.

Cleaning such a wound was time-consuming and often ineffective. Shattered bones and infections frequently left surgeons with no other recourse but amputation. Amputation replaced a complex wound with a simpler wound above the original. Surgical manuals taught that an amputation should be performed within the first two days following injury. The death rate from "primary amputations" was lower than the rate for amputations performed after the wound became infected. Union surgeons performed nearly 30,000 amputations; Confederate surgeons are believed to have performed the same number.

Chest and Abdominal Wounds

Treatment of abdominal wounds often involved pushing in protruding organs and suturing the wound. Chest wounds were cleaned and the wound was sutured. Food was withheld because fecal material leaking from the intestines caused contamination. Opium was often administered to halt the action of the digestive system. Abdominal wounds were fatal in almost 90 percent of the cases reported by Union surgeons.

Cases of interest include:

Major General D.E. Sickle, U.S. Volunteers was wounded on the evening of the second day of the battle of Gettysburg, by a twelve pounder solid shot which shattered his right leg. General Sickles was on horseback at the time, and unattended, he succeeded in quieting his freighted horse and in dismounting unassisted. According to the narrative that accompanies the photograph of the specimen for this case, "he was removed a short distance to the rear to a sheltered ravine, and amputation was performed low down in the thigh, by Surgeon Thomas Sim, U.S. Vols., Medical Director of the 3d Army Corps. The patient was then sent to the rear, and the following day was transferred to Washington. The stump healed with great rapidity. On July 16th, the patient was able to ride about in a carriage. Early in September, 1863, the stump was completely cicatrized, and the general was able again, to mount his horse. The specimen was contributed to the Army Medical Museum by General Sickles, and the facts of the case by his staff surgeon, Dr. Sim."

Captain Robert Stolpe of Company A, 29th New York Volunteers, who was wounded at Chancellorsville, on the 2nd of May, 1863. The narrative states that, "a round musket ball, fired from a distance of about one hundred and fifty yards, entered the eighth intercostal space of the left side, at a point nine and a half inches to the left of the extremity of the ensifonn cartilage, and fractured the ninth rib. Without wounding the lung, apparently, the ball passed through the diaphragm, and entered some portion of the alimentary canal. Captain Stolpe walked a mile and a half to the rear, and entered a field hospital. On examining the wound, the surgeons found a protrusion of the lung of the size of a small orange, which they unavailingly attempted to reduce. The wound was enlarged, and still it was impracticable to replace the protruded lung. On May 3rd, the field hospital where Captain Stolpe lay, was exposed to the enemy's fire. He walked half a mile farther to the rear, and was there placed in an ambulance and taken across the Rappahannock, at United States Ford, to one of the base hospitals. Here fruitless efforts were again made to reduce the hernial tumor, after which a ligature was thrown around its base and tightened. A day or two subsequently the patient passed into the hands of Surgeon Tomaine, who removed the ligature from the base of the tumor. A small portion of the gangrenous lung separated and left a clean granulating surface beneath. On May 7th, the ball was voided at stool. On May 8th, the patient was visited by Surgeon John H. Brinton, U. S. Vols., who found him walking about the ward, smoking a cigar. There was an entire absence of general constitutional symptoms; no cough, no dyspnoea, no abdominal pain; the bowels were regular and appetite good. The protruding portion of lung was carnified..."

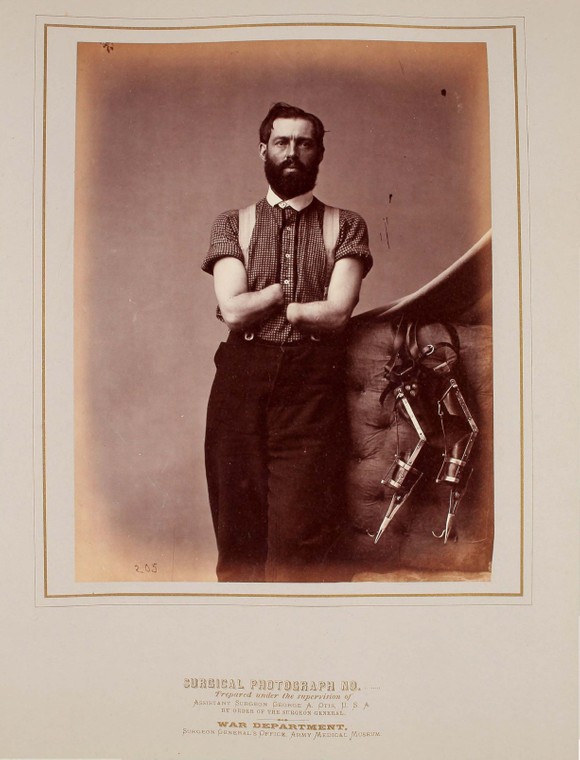

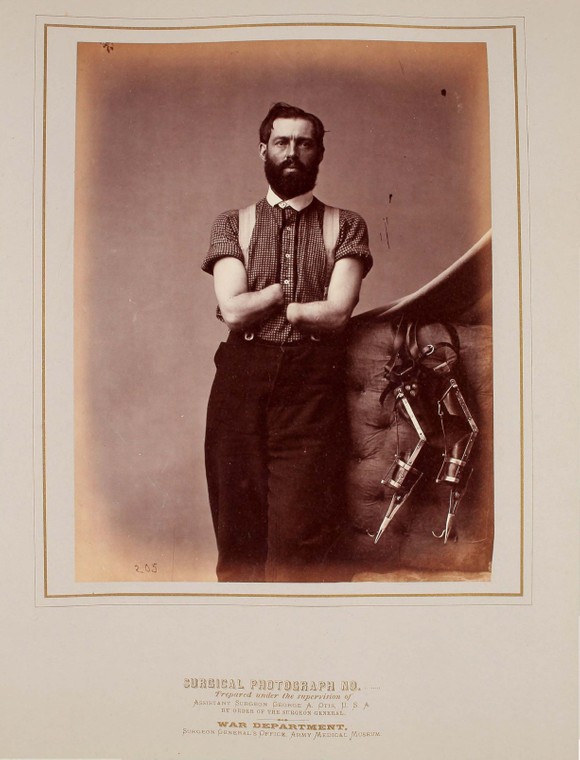

Private Samuel H. Decker, Co. I, 4th U. S. Artillery, photographed November 29, 1867. Decker's hands were destroyed in a gun accident during the 1862 battle of Perryville, Kentucky. Decker designed his own prostheses to adapt to his disability. He later served as doorkeeper for the House of Representatives. The narrative accompanying his photo states that, "while ramming his piece at the battle of Perryville, Kentucky, October 8, 1862, had half of his right forearm, and somewhat less of the left, blown off by the premature explosion of the gun. At the same time his face and chest were badly burned. Five hours after the accident, both forearms were amputated by the circular method, about the middle, by an Assistant Surgeon of the regular army whose name he cannot recall..." "In the Autumn of 1864, Mr. Decker began to make experiments for providing himself with artificial limbs. He produced, in March, 1865, an apparatus hitherto unrivaled for its ingenuity and utility. He receives a pension of $300.00 per year, and is a doorkeeper at the House of Representatives. On November 20, 1867, Mr. Decker visited the Army Medical Museum, where a number of photographs of his stumps were made. With the aid of his ingenious apparatus he is enabled to write legibly, to pick up any small objects, a pin for example, to carry packages of ordinary weight, to feed and clothe himself, and in one or two instances of disorder in the Congressional gallery has proved himself a formidable police officer."

660 pages in six volumes of photos commissioned by the United States surgeon general and case summaries of injuries suffered during the Civil War.

The photographs in this collection contain graphic medical images of injuries and anatomy, which may not be suitable for all audiences. The reproductions of these volumes are unedited.

These images flout some of the romanticism often imposed on the Civil War and show the real faces, injuries, and sacrifices regularly made by Civil War fighters, both Union and Confederate.

According to the National Museum of Health and Medicine of the approximately 3 million soldiers and sailors who participated in Civil War combat approximately 618,000 died, nearly 400,000 of these deaths were due to disease. The death toll was nearly 2% of the entire population. Among the 79% of combatants who survived the war, nearly half a million returned home permanently maimed or disabled.

The photographs and illustrations in this collection are vivid. They starkly illustrate the traumatic effects of recently developed warfare technology of the Civil War era on the human body. The collection contains detailed case histories written by the staff of the Army Medical Museum. The entries accompany each photograph and record the names and ranks of soldiers, specific battles where the injury occurred, dates of injury, treatment narratives, and final outcomes. This material compiled in the 1860's, now provide a wealth of medical and biographical information to historians and other interested parties.

The materials in these volumes were prepared by direction of the Surgeon General's Office, by Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George A. Otis, Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A., Curator of the Army Medical Museum. Founded in 1862 by Surgeon General William Hammond of the Union Army, the Army Medical Museum was a clearinghouse for medical information collected from Union surgeons.

Surgeon General William Hammond directed medical officers in the field to collect "specimens of morbid anatomy together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" and to forward them to the newly founded museum for study. The Museum's first curator, John Brinton, visited mid-Atlantic battlefields and solicited contributions from doctors throughout the Union Army. During and after the war, Museum staff took pictures of wounded soldiers showing effects of gunshot wounds, as well as results of amputations and other surgical procedures.

Many of these anatomical specimens collected on behalf of the Army Medical Museum (now called the National Museum of Health and Medicine) by Dr. John Hill Brinton are photographed in this collection. The compilation and photography of subjects was supervised by Dr. George Alexander Otis, who succeeded Brinton as curator of the museum in 1864. William Bell, famous for his later images of the American West, served as Chief Photographer for the museum from 1865 to 1868, and photographed many of the portrait sitters and specimens himself.

This collection contains 300 case narratives, 286 photographs of patients and specimens, and 14 illustrations. The cases and specimens were chosen by museum staff from the thousands of pieces of material available at the Army Medical Museum as the most important for study.

Scope and Content

The six volumes contain mounted albumen photographic prints with accompanying case histories, Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens contains extensive visual documentation of patients who suffered traumatic wounds during and shortly after the Civil War. The majority of the subjects were soldiers, both Union and Confederate, though the later volumes in the series, compiled and published after the war, include civilian cases that were considered relevant additions to the collection. The work contains both portraiture and specimen photography, as well as a small number of photographically-reproduced drawings and paintings. The majority of specimens illustrate fractures or necrotic bone degeneration arising from shrapnel or gunshot wounds.

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate soldiers received approximately 350,000 wounds to the extremities leading to about 60,000 amputations.

Surgery in the 1860's

Before the Civil War, military medical care was the duty of the regimental surgeon and surgeons' mates. The war saw attempts to establish a centralized medical system. The availability of effective treatment for disease and injury was, by modern standards, primitive. During battles undersupplied and understaffed medical departments often worked within the limitations of battlefield hospitals just beyond the range of gunfire. Although medical personnel made every effort to treat the wounded quickly and efficiently, severely injured men often received little or no treatment for one to two days after a major engagement.

Significant changes began to occur during the Civil War, when improvements in medical science, communications and transportation made centralized casualty collection and treatment more practical. Despite the lack of both surgical experience and sanitary conditions, the survival rate among those who underwent wartime surgery was better than in previous wars. Amputation was not the only surgical recourse available. Surgeons also extracted bullets, operated on fractured skulls, reconstructed damaged facial structures, and removed sections of broken bones. According to the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Union surgeons documented nearly 250,000 wounds from bullets, shrapnel, and other missiles. Fewer than 1,000 cases were reported of wounds caused by sabers and bayonets.

Amputations

During the Civil War surgeons often found it necessary to treat arm and leg wounds by amputating. The complex wounds caused by bullets and shrapnel were often contaminated by foreign material. The dreaded minié ball tore through the flesh, splintered bone and destroyed tissue beyond repair. Fragments of bone along with dirt, torn cloth and germs caused infections.

Cleaning such a wound was time-consuming and often ineffective. Shattered bones and infections frequently left surgeons with no other recourse but amputation. Amputation replaced a complex wound with a simpler wound above the original. Surgical manuals taught that an amputation should be performed within the first two days following injury. The death rate from "primary amputations" was lower than the rate for amputations performed after the wound became infected. Union surgeons performed nearly 30,000 amputations; Confederate surgeons are believed to have performed the same number.

Chest and Abdominal Wounds

Treatment of abdominal wounds often involved pushing in protruding organs and suturing the wound. Chest wounds were cleaned and the wound was sutured. Food was withheld because fecal material leaking from the intestines caused contamination. Opium was often administered to halt the action of the digestive system. Abdominal wounds were fatal in almost 90 percent of the cases reported by Union surgeons.

Cases of interest include:

Major General D.E. Sickle, U.S. Volunteers was wounded on the evening of the second day of the battle of Gettysburg, by a twelve pounder solid shot which shattered his right leg. General Sickles was on horseback at the time, and unattended, he succeeded in quieting his freighted horse and in dismounting unassisted. According to the narrative that accompanies the photograph of the specimen for this case, "he was removed a short distance to the rear to a sheltered ravine, and amputation was performed low down in the thigh, by Surgeon Thomas Sim, U.S. Vols., Medical Director of the 3d Army Corps. The patient was then sent to the rear, and the following day was transferred to Washington. The stump healed with great rapidity. On July 16th, the patient was able to ride about in a carriage. Early in September, 1863, the stump was completely cicatrized, and the general was able again, to mount his horse. The specimen was contributed to the Army Medical Museum by General Sickles, and the facts of the case by his staff surgeon, Dr. Sim."

Captain Robert Stolpe of Company A, 29th New York Volunteers, who was wounded at Chancellorsville, on the 2nd of May, 1863. The narrative states that, "a round musket ball, fired from a distance of about one hundred and fifty yards, entered the eighth intercostal space of the left side, at a point nine and a half inches to the left of the extremity of the ensifonn cartilage, and fractured the ninth rib. Without wounding the lung, apparently, the ball passed through the diaphragm, and entered some portion of the alimentary canal. Captain Stolpe walked a mile and a half to the rear, and entered a field hospital. On examining the wound, the surgeons found a protrusion of the lung of the size of a small orange, which they unavailingly attempted to reduce. The wound was enlarged, and still it was impracticable to replace the protruded lung. On May 3rd, the field hospital where Captain Stolpe lay, was exposed to the enemy's fire. He walked half a mile farther to the rear, and was there placed in an ambulance and taken across the Rappahannock, at United States Ford, to one of the base hospitals. Here fruitless efforts were again made to reduce the hernial tumor, after which a ligature was thrown around its base and tightened. A day or two subsequently the patient passed into the hands of Surgeon Tomaine, who removed the ligature from the base of the tumor. A small portion of the gangrenous lung separated and left a clean granulating surface beneath. On May 7th, the ball was voided at stool. On May 8th, the patient was visited by Surgeon John H. Brinton, U. S. Vols., who found him walking about the ward, smoking a cigar. There was an entire absence of general constitutional symptoms; no cough, no dyspnoea, no abdominal pain; the bowels were regular and appetite good. The protruding portion of lung was carnified..."

Private Samuel H. Decker, Co. I, 4th U. S. Artillery, photographed November 29, 1867. Decker's hands were destroyed in a gun accident during the 1862 battle of Perryville, Kentucky. Decker designed his own prostheses to adapt to his disability. He later served as doorkeeper for the House of Representatives. The narrative accompanying his photo states that, "while ramming his piece at the battle of Perryville, Kentucky, October 8, 1862, had half of his right forearm, and somewhat less of the left, blown off by the premature explosion of the gun. At the same time his face and chest were badly burned. Five hours after the accident, both forearms were amputated by the circular method, about the middle, by an Assistant Surgeon of the regular army whose name he cannot recall..." "In the Autumn of 1864, Mr. Decker began to make experiments for providing himself with artificial limbs. He produced, in March, 1865, an apparatus hitherto unrivaled for its ingenuity and utility. He receives a pension of $300.00 per year, and is a doorkeeper at the House of Representatives. On November 20, 1867, Mr. Decker visited the Army Medical Museum, where a number of photographs of his stumps were made. With the aid of his ingenious apparatus he is enabled to write legibly, to pick up any small objects, a pin for example, to carry packages of ordinary weight, to feed and clothe himself, and in one or two instances of disorder in the Congressional gallery has proved himself a formidable police officer."

1 file (188.3MB)