Starting from:

$12.95

World War II: Official U.S. Army Campaign Histories - 38 Volumes

World War II: Official U.S. Army Campaign Histories - 38 Volumes

1,216 pages of United States Army official campaign histories, composed of text, 220 photos, 134 maps, and 35 hand-drawn illustrations,.

History compiled by the Center of Military History United States Army, covering World War II campaigns in Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, The Pacific and Asia. The volumes published in 1992, cover campaign backgrounds, strategic settings, operations, and provides analysis.

World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. Highly relevant today, World War II has much to teach us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations. World War II was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over several diverse theaters of operation for approximately six years. This series of campaign studies highlighting those struggles are designed to introduce military feats from World War II.

Thirty-eight condensed histories ranging from 20 to 56 pages each. Campaign books include:

Aleutian Islands: 3 June 1942–24 August 1943

Algeria–French Morocco: 8 November 1942–11 November 1942

Anzio: 22 January–24 May 1944

Ardennes-Alsace: 16 December 1944–25 January 1945

Bismarck Archipelago: 15 December 1943–27 November 1944

Burma, 1942: 7 December 1941-26 May 1942

Central Europe 22 March–11 May 1945

Central Pacific: 7 December 1941-6 December 1943

Central Burma: 29 January–15 July 1945

China Defensive: 4 July 1942–4 May 1945

China Offensive: 5 May–2 September 1945

East Indies: 1 January–22 July 1942

Eastern Mandates: 31 January–14 June 1944

Egypt-Libya: 11 June 1942–12 February 1943

Guadalcanal: 7 August 1942–21 February 1943

India-Burma: 2 April 1942–28 January 1945

Leyte: 17 October 1944 1 July 1945

Luzon: 15 December 1944–4 July 1945

Naples-Foggia: 9 September 1943–21 January 1944

New Guinea: 24 January 1943–31 December 1944

Normandy: 6 June–24 July 1944

North Apennines: 10 September 1944–4 April 1945

Northern France: 25 July–14 September 1944

Northern Solomons: 22 February 1943–21 November 1944

Papua: 23 July 1942–23 January 1943

Philippine Islands: 7 December 1941–10 May 1942

Po Valley: 5 April–8 May 1945

Rhineland: 15 September 1944–21 March 1945

Rome-Arno: 22 January–9 September 1944

Ryukyus: 26 March–2 July 1945

Sicily Campaign: 9 July–17 August 1943

Southern France: 15 August–14 September 1944

Southern Philippines: 27 February–4 July 1945

Tunisia: 17 November 1942–13 May 1943

Western Pacific: 15 June 1944–2 September 1945

Plus "A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II","Defense of the Americas" and "Mobilization in World War II."

Aleutian Islands: 3 June 1942–24 August 1943

Protruding in a long, sweeping curve for more than a thousand miles westward from the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula, the Aleutians provided a natural avenue of approach between Japan and the United States. Japanese concern for the defense of the northern Pacific increased when sixteen U.S. B-25 bombers, led by Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, took off from the carrier Hornet and bombed Tokyo on 18 April 1942. Unsure of where the American raid originated, but suspicious that it could have been from a secret base in the western Aleutians, the Imperial High Command began to take an active interest in capturing the island chain.

The Aleutians first appeared as a Japanese objective in a plan prepared under the direction of one of Japan's most able commanders, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. An attack on the Aleutians in early June 1942, Yamamoto believed, would draw the U.S. fleet north to challenge his forces.

Algeria–French Morocco: 8 November 1942–11 November 1942

Events bringing the United States Army to North Africa had begun more than a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. For both the Axis and the Allies, the Mediterranean Sea area was one of uncertain priority. On the Axis side, the location of Italy made obvious Rome's interest in the region. But the stronger German partner pursued interests hundreds of miles north. A similar division of emphasis characterized the Allies. To the British the Mediterranean Sea was the vital link between the home islands and long-held Asian possessions as well as Middle Eastern oil fields. To the Americans, however, the area had never been one of vital national interest and was not seen as the best route to Berlin. But the fall of France in June 1940 had also brought a new dimension to the region. The surrender of Paris left 120,000 French troops in West and North Africa and much of the French fleet in Atlantic and Mediterranean ports. Both the Axis and Allies saw overseas French forces as the decisive advantage that would allow them to achieve their contradictory objectives in the Mediterranean.

Anzio: 22 January–24 May 1944

The four months of this campaign would see some of the most savage fighting of World War II.

Following the successful Allied landings at Calabria, Taranto, and Salerno in early September 1943 and the unconditional surrender of Italy that same month, German forces had quickly disarmed their former allies and begun a slow, fighting withdrawal to the north. Defending two hastily prepared, fortified belts stretching from coast to coast, the Germans significantly slowed the Allied advance before settling into the Gustav Line, a third, more formidable and sophisticated defensive belt of interlocking positions on the high ground along the peninsula's narrowest point.

During the four months of the Anzio Campaign the Allied VI Corps suffered over 29,200 combat casualties (4,400 killed, 18,000 wounded, 6,800 prisoners or missing) and 37,000 noncombat casualties. Two-thirds of these losses, amounting to 17 percent of VI Corps' effective strength, were inflicted between the initial landings and the end of the German counteroffensive on 4 March. Of the combat casualties, 16,200 were Americans (2,800 killed, 11,000 wounded, 2,400 prisoners or missing) as were 26,000 of the Allied noncombat casualties. German combat losses, suffered wholly by the Fourteenth Army, were estimated at 27,500 (5,500 killed, 17,500 wounded, and 4,500 prisoners or missing), figures very similar to Allied losses.

The Anzio Campaign continues to be controversial, just as it was during its planning and implementation stages. The operation, according to U.S. Army Center of Military History historian Clayton D. Laurie, clearly failed in its immediate objectives of outflanking the Gustav Line, restoring mobility to the Italian campaign, and speeding the capture of Rome.

Yet the campaign did accomplish several goals. The presence of a significant Allied force behind the German main line of resistance, uncomfortably close to Rome, represented a constant threat. The Germans could not ignore Anzio and were forced into a response, thereby surrendering the initiative in Italy to the Allies. The 135,000 troops of the Fourteenth Army surrounding Anzio could not be moved elsewhere, nor could they be used to make the already formidable Gustav Line virtually impregnable.

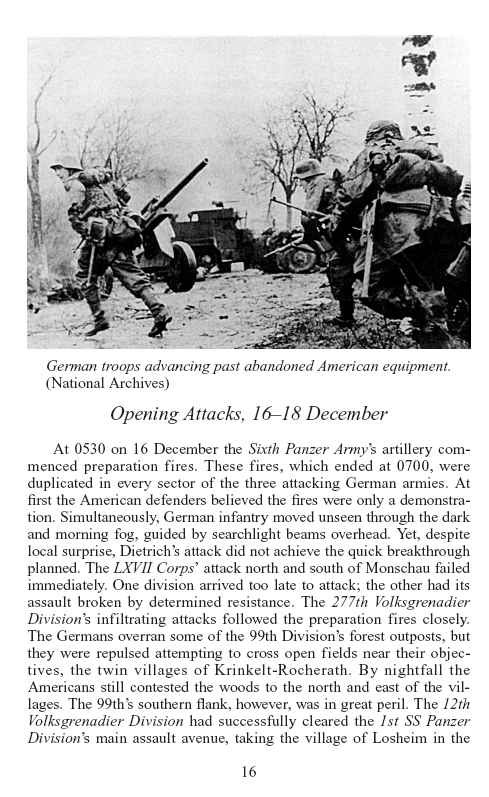

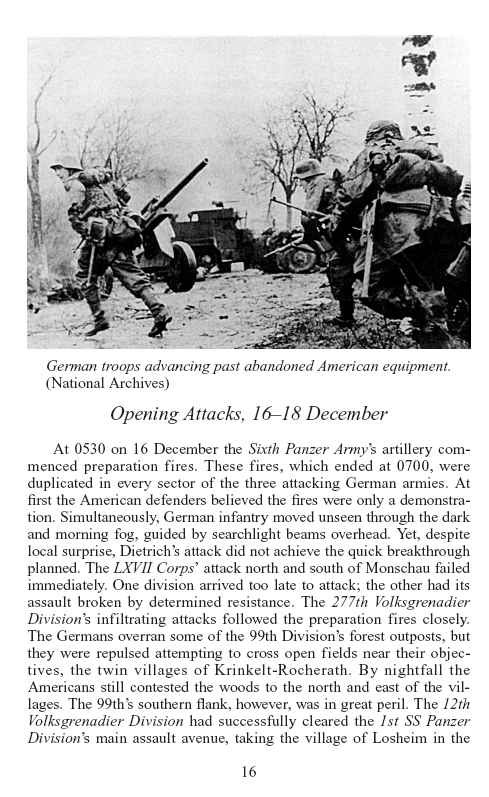

Ardennes-Alsace: 16 December 1944–25 January 1945

In August 1944, while his armies were being destroyed in Normandy, Hitler secretly put in motion actions to build a large reserve force, forbidding its use to bolster Germany's beleaguered defenses. To provide the needed manpower, he trimmed existing military forces and conscripted youths, the unfit, and old men previously untouched for military service during World War II.

In September Hitler named the port of Antwerp, Belgium, as the objective. Selecting the Eifel region as a staging area, Hitler intended to mass twenty-five divisions for an attack through the thinly held Ardennes Forest area of southern Belgium and Luxembourg. Once the Meuse River was reached and crossed, these forces would swing northwest some 60 miles to envelop the port of Antwerp. The maneuver was designed to sever the already stretched Allied supply lines in the north and to encircle and destroy a third of the Allies' ground forces. If successful, Hitler believed that the offensive could smash the Allied coalition, or at least greatly cripple its ground combat capabilities, leaving him free to focus on the Russians at his back door.

Bismarck Archipelago: 15 December 1943–27 November 1944

By the close of 1943, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand had stopped the Japanese juggernaut in the Pacific. To put the Japanese on the defensive, within the framework of the global strategy adopted by American and British leaders, the Allies initiated offensive operations along two mutually supporting lines of advance. Admiral Chester Nimitz, who commanded operations in the Central Pacific, invaded the Gilbert Islands in the Allied drive toward Japan, while General Douglas MacArthur, commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, initiated a series of amphibious assault operations along the New Guinea coast. These operations were the first steps in his drive to return to the Philippines, a pledge he had made when he left the islands in 1942.

Before MacArthur could begin operations against the Philippines, he needed to capture the Bismarck Archipelago, a group of islands off the New Guinea coast. Continued enemy control of the region would otherwise jeopardize his campaign. The struggle for these islands, New Britain, New Ireland, the Admiralties, and several smaller islands, was officially designated as the Bismarck Archipelago Campaign.

Burma, 1942: 7 December 1941-26 May 1942

Early in 1942 Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell arrived in the Far East to command American forces in what became the China-Burma-India theater and to serve as chief of staff and principal adviser to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the political and military leader of Nationalist China. Stilwell's mission was to improve the efficiency of Chiang's army, which had been fighting the Japanese since 1937, and to keep China in the war. But the Japanese conquest of Burma later in 1942 cut the last overland supply route to China and frustrated Stilwell's plans.

The loss of Burma was a serious blow to the Allies. It completed the blockade of China, and without Allied aid, China's ability to oppose the Japanese invasion was extremely limited. Militarily, according to U.S. Army Center of Military History historian Clayton D. Laurie, the Allied failure in Burma can be attributed to unpreparedness on the part of the British to meet the Japanese invasion and the failure of the Chinese to assist wholeheartedly in the defense.

Central Burma: 29 January–15 July 1945

The final campaign for clearing Japanese invaders from Burma was well under way by the start of 1945 with a desperate enemy grudgingly giving ground before a more powerful Allied force composed of units the majority of which were Chinese and Indian veterans. Their Japanese opponent, still a formidable challenge, was a ruthless and bold soldier who obediently fought and marched until he died or killed himself.

Central Europe 22 March–11 May 1945

By the beginning of the Central Europe Campaign of World War II, Allied victory in Europe was inevitable. Having gambled his future ability to defend Germany on the Ardennes offensive and lost, Hitler had no real strength left to stop the powerful Allied armies. Yet Hitler forced the Allies to fight, often bitterly, for final victory. Even when the hopelessness of the German situation became obvious to his most loyal subordinates, Hitler refused to admit defeat. Only when Soviet artillery was falling around his Berlin headquarters bunker did the German Fuehrer begin to perceive the final outcome of his megalomaniacal crusade.

Central Pacific: 7 December 1941-6 December 1943

The Central Pacific Campaign, one of the longest in World War II, had a clear and definite beginning with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Its termination on 6 December 1943, however, was apparently determined more by a desire to make it a tidy two-year campaign than by the attainment of any particular strategic objective. The campaign was mainly defensive, although the Battle of Midway and Operation GALVANIC were notable offensive operations. The former finally brought the Japanese offensive to a halt, and the latter marked the opening of the American drive across the Pacific that would eventually end World War II.

Most of the Central Pacific Campaign took place in Micronesia, an area of the globe larger than the continental United States, where a multitude of islands lie scattered about a vast expanse of ocean. Clustered into four major groups, these Pacific islands have a landmass of about 1,200 square miles, an area somewhat larger than the state of Rhode Island. The most easterly of the four island groups are the Gilberts, low-lying coral atolls, straddling the equator just west of the international date line. North and west of the Gilberts are the Marshall Islands, a double chain of atolls, reefs, and islets, most of which rise only a few feet above sea level. Stretching almost due west from the Marshalls are the 550 tiny islands of the Caroline group. The Marianas lie just north of the Carolines in a 400-mile north-south chain.

China Defensive: 4 July 1942–4 May 1945

The China theater posed unique problems for the U.S. military. Unlike Western Europe, where key partners employed comparable resources, operations in China involved only a handful of U.S. ground and logistical units in support of huge Chinese armies. Moreover, civil strife in China, which long predated the outbreak of World War II and was, at best, only obscured by the struggle with Imperial Japan, made any conventional approach to American support unrealistic. Within both the Nationalist Chinese and Red Chinese armies, internal politics and military reform were inextricably linked, and any hope of creating an effective and conventional Chinese military while temporarily shelving China's internal political problems was unrealistic.

The U.S. Army's main role in China was to keep China in the war through the provision of advice and materiel assistance. As long as China stayed in the war, hundreds of thousands of Imperial Japanese Army soldiers could be tied down on the Asian mainland. Success was thus measured differently than in most theaters. How well both General Stilwell and General Wedemeyer persuaded the theater commander-in-chief, Generalissimo Chiang, to support U.S. strategic goals, and how effectively U.S. training and materiel support could build selected Chinese Army divisions into modern tactical units, capable of standing up to Japanese adversaries, were secondary objectives. What mattered most was simply keeping China in the war against Japan.

China Offensive: 5 May–2 September 1945

As victory in Europe appeared increasingly inevitable in the early months of 1945, the Allies began to focus greater military resources on the war against Japan. Throughout the spring of 1945 Allied forces drove the Japanese from Burma and dislodged Japanese forces from key islands in the central and southwest Pacific. With its sea power shattered and its air power outmatched, Japan's only remaining resource was its relatively intact ground force. Although the land campaigns in Burma and the Philippines had been disastrous for the engaged Japanese forces, those and other outlying garrisons represented only a small percent of its ground troops. The bulk of Japan's army of over two million men was on the mainland of Asia, primarily in China.

On 14 February 1945, General Wedemeyer submitted his plan for the Chinese offensive to Chiang Kai-shek, who immediately approved it. The plan had four phases: the capture of the Liuchow-Nanning area; the consolidation of the captured area; the concentration of forces needed for an advance to the Hong Kong–Canton coastal region; and an offensive operation to capture Hong Kong and Canton. The Joint Chiefs of Staff eventually approved the plan on 20 April.

East Indies: 1 January–22 July 1942

The experience of 2d Battalion, 131st Field Artillery, and the loss of thousands of Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen in the East Indies stands as a reminder of Allied unpreparedness in the Pacific in 1941.

Eastern Mandates: 31 January–14 June 1944

One of the island groups targeted for invasion in the Joint Chiefs' plan was the Eastern Mandates, better known as the Marshall Islands. Under German control from the late 1890s through the end of World War I, the Marshalls had been assigned to the Japanese as mandates in accord with Article 22 of the League of Nations Charter.

Egypt-Libya: 11 June 1942–12 February 1943

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the British had been fighting German and Italian armies in the Western Desert of Egypt and Libya for over a year. In countering an Italian offensive in 1940, the British had at first enjoyed great success. In 1941, however, when German forces entered the theater in support of their Italian ally, the British suffered severe reversals, eventually losing nearly all their hard-won gains in North Africa.

The Egypt-Libya Campaign was one of the smaller, less well known U.S. Army campaigns of World War II. Its significance, however, cannot be measured simply by counting Army forces involved. The campaign made a major contribution to Allied success in World War II by laying a firm foundation of Anglo-American cooperation.

Guadalcanal: 7 August 1942–21 February 1943

Victory on Guadalcanal brought important strategic gains to the Americans and their Pacific allies but at high cost. Combined with the American-Australian victory at Buna on New Guinea, success in the Solomons turned back the Japanese drive toward Australia and staked out a strong base from which to continue attacks against Japanese forces,

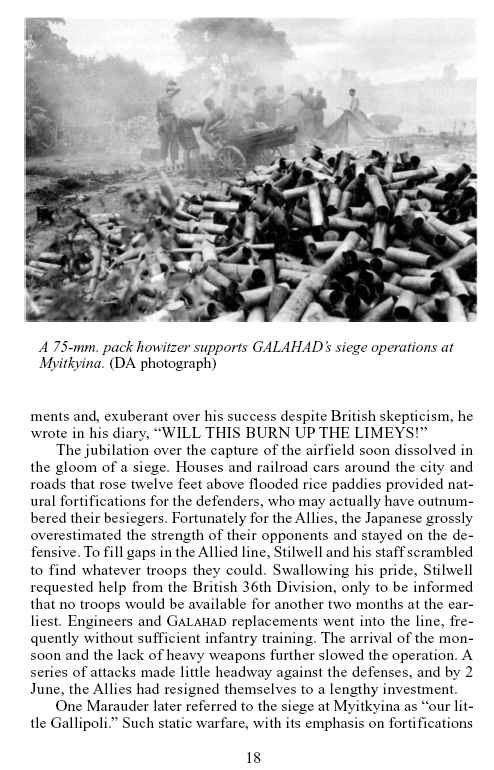

India-Burma: 2 April 1942–28 January 1945

"Historians have found it fashionable to characterize the CBI as a forgotten theater, low in the Allied list of priorities," according to U.S. Army Center of Military historian David W. Hogan. "To be sure, the European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters all enjoyed greater access to scarce manpower and material than the CBI, which had to cope with an extended line of supply back to the United States. Only a few American combat troops served in China, Burma, or India. Yet one can hardly call the CBI an ignored theater. It occupied a prominent place in Allied councils, as Americans sought an early Allied commitment to reopening China's lifeline so that China could tie down massive numbers of Japanese troops and serve as a base for air, naval, and eventually amphibious operations against the Japanese home islands."

Leyte: 17 October 1944 1 July 1945

By the summer of 1944, American forces had fought their way across the Pacific on two lines of attack to reach a point 300 miles southeast of Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippines. In the Central Pacific, forces under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean areas, had island-hopped through the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and the Carolines. More than 1,000 miles to the south, Allied forces under General Douglas MacArthur, commanding the Southwest Pacific area, had blocked the Japanese thrust toward Australia, and then recaptured the Solomons and New Guinea and many of its outlying islands, isolating the huge Japanese base at Rabaul.

These victories brought American forces to the inner defensive line of the Japanese Empire, and in the summer of 1944 they pushed through that barrier to take the Marianas, the Palaus, and Morotai. With the construction of airfields in the Marianas, US. Army Air Forces were within striking distance of the Japanese home islands for the first time during the war. Yet, despite an unbroken series of defeats during two years of fighting, the Japanese showed no inclination to end the war. As American forces closed on Japan, they thus faced the most formidable outposts of the Japanese Empire: the Philippines, Formosa, and Okinawa.

The campaign for Leyte proved the first and most decisive operation in the American reconquest of the Philippines. The Japanese invested heavily in Leyte, and lost. The campaign cost their army four divisions and several separate combat units, while their navy lost twenty-six major warships, and forty-six large transports and merchantmen. The struggle also reduced Japanese land-based air capability in the Philippines by more than 50 percent, forcing them to depend on suicidal kamikaze pilots.

Luzon: 15 December 1944–4 July 1945

"The Philippine theater of operations is the locus of victory or defeat," argued General Douglas MacArthur, as Japanese planes strafed and bombed key installations around Manila on 8 December 1941. Although overwhelming Japanese strength ultimately forced the United States to relinquish the Philippines, MacArthur began planning his return almost immediately from bases in Australia. Throughout the long campaign to push the Japanese out of their Pacific bastions, these islands remained his crucial objective. "The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines...for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary object of which is the relief of the Philippines," MacArthur said when he took over as Allied commander in the Southwest Pacific. "I came through and I shall return." As the Pacific campaign dragged on, MacArthur never strayed far from that goal, and every move he made was aimed ultimately at recapturing the lost archipelago.

Naples-Foggia: 9 September 1943–21 January 1944

The Allied goals, established before the invasion of Italy, were to gain control of the Mediterranean, keep pressure on the Germans while building for the cross-Channel attack, and force Italy to withdraw from the war. All agreed that bases in Italy would provide support for the air war against German sources of supply in the Balkans and the German industrial heartland itself. These sound strategic goals were valid in 1943 and have stood the test of time. By late August, the Italian government had decided to withdraw from the war and break relations with Germany. The fall of Sicily had enhanced Allied control of the Mediterranean but had not assured it. Prior to the invasion of Italy, therefore, the Allied goals were far from being totally satisfied, and an eager world watched as the Allies launched first Operation BAYTOWN and then Operation AVALANCHE to invade the European continent.

New Guinea: 24 January 1943–31 December 1944

The campaign on New Guinea is all but forgotten except by those who served there. Battles with names like Tarawa, Saipan, and Iwo Jima overshadow it. Yet Allied operations in New Guinea were essential to the U.S. Navy's drive across the Central Pacific and to the U.S. Army's liberation of the Philippine Islands from Japanese occupation. The remorseless Allied advance along the northern New Guinea coastline toward the Philippines forced the Japanese to divert precious ships, planes, and men who might otherwise have reinforced their crumbling Central Pacific front.

In January 1943 the Allied and the Japanese forces facing each other on New Guinea were like two battered heavyweights. Round one had gone to the Americans and Australians who had ejected the Japanese from Papua, New Guinea. After three months of unimaginative frontal attacks had overcome a well-entrenched foe, General Douglas MacArthur, the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) commander, had his airstrip and staging base at Buna on the north coast. It was expensive real estate. About 13,000 Japanese troops perished during the terrible fighting, but Allied casualties were also heavy; 8,500 men fell in battle (5,698 of them Australians) and 27,000 cases of malaria were reported, mainly because of shortages of medical supplies.

Normandy: 6 June–24 July 1944

A great invasion force stood off the Normandy coast of France as dawn broke on 6 June 1944: 9 battleships, 23 cruisers, 104 destroyers, and 71 large landing craft of various descriptions as well as troop transports, mine sweepers, and merchantmen—in all, nearly 5,000 ships of every type, the largest armada ever assembled. The naval bombardment that began at 0550 that morning detonated large minefields along the shoreline and destroyed a number of the enemy's defensive positions. To one correspondent, reporting from the deck of the cruiser HMS Hillary, it sounded like "the rhythmic beating of a gigantic drum" all along the coast. In the hours following the bombardment, more than 100,000 fighting men swept ashore to begin one of the epic assaults of history, a "mighty endeavor," as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it to the American people, "to preserve. . . our civilization and to set free a suffering humanity."

North Apennines: 10 September 1944–4 April 1945

The northern Apennines fighting was the penultimate campaign in the Italian theater. Although the Allies steadily lost divisions, materiel, and shipping to operations elsewhere, which diminished their capabilities, their offensives prevented the Axis from substantially reinforcing other fronts with troops from Italy. Yet the transfer of units from Fifth and Eighth Armies for use in northwest Europe, southern France, and Greece, both after the capture of Rome and during the North Apennines Campaign itself, left Allied commanders with just enough troops to hold Axis forces in Italy but without sufficient forces to destroy the enemy or to end the campaign.

Northern France: 25 July–14 September 1944

As July 1944 entered its final week, Allied forces in Normandy faced, at least on the surface, a most discouraging situation. In the east, near Caen, the British and Canadians were making little progress against fierce German resistance. In the west, American troops were bogged down in the Norman hedgerows. These massive, square walls of earth, five feet high and topped by hedges, had been used by local farmers over the centuries to divide their fields and protect their crops and cattle from strong ocean winds. The Germans had turned these embankments into fortresses, canalizing the American advance into narrow channels, which were easily covered by antitank weapons and machine guns. The stubborn defenders were also aided by some of the worst weather seen in Normandy since the turn of the century, as incessant downpours turned country lanes into rivers of mud. By 25 July, the size of the Allied beachhead had not even come close to the dimensions that pre–D-day planners had anticipated, and the slow progress revived fears in the Allied camp of a return to the static warfare of World War I. Few would have believed that, in the space of a month and a half, Allied armies would stand triumphant at the German border.

Northern Solomons: 22 February 1943–21 November 1944

The Northern Solomons is one of the more unheralded of the U.S. Army campaigns of World War II, largely overshadowed by its predecessor, Guadalcanal, and by its more publicized successor, Leyte. Furthermore, with hindsight the campaign for the northern Solomon Islands might be described simply as bringing to bear preponderant American strength on isolated Japanese positions. Such a summary does describe accurately what American strategy skillfully achieved through sustained joint operations: the isolation and subsequent defeat in detail of Japanese forces.

Papua: 23 July 1942–23 January 1943

The United States Army learned much from the Papua Campaign but at a high cost. Allied losses totaled 8,546 killed and wounded. Of those, the 32d Division lost 687 killed in action and 2,161 wounded or lost from other causes. The lack of leaders experienced in jungle fighting accounted in part for these losses. Because the campaign was the Army's first in a world war tropical theater, everyone involved had to learn while under fire. The last combat experience of the Allied leaders had ended in 1918. The Australians had spent recent years in the Middle East. Only General MacArthur, with years of duty in the Philippines, brought to the campaign any familiarity with jungle fighting, but as theater commander he exercised leadership far from the front. The necessarily trial-and-error tactical approach of the Allies in the early stages of the campaign inevitably delayed the victory.

Philippine Islands: 7 December 1941–10 May 1942

The valiant defense of the Philippines had several important consequences. It delayed the Japanese timetable for the conquest of south Asia, causing them to expend far more manpower and materiel resources than anticipated. Probably of equal importance, the determined resistance against overwhelming odds became a symbol of hope for the United States in the early, bleak days of the war. When surrender came, the image of the self-proclaimed "Battling Bastards of Bataan" inspired the Allied troops to honor such sacrifices by vowing to retake the islands. MacArthur himself became an important symbol of America's pledge to return to the Far East.

Po Valley: 5 April–8 May 1945

For the Allied armies in Italy, the Po Valley offensive climaxed the long and bloody Italian campaign. When the spring offensive opened, it initially appeared that its course might continue the pattern of the previous months and battles in Italy, becoming another slow, arduous advance over rugged terrain, in poor weather, against a determined, well-entrenched, and skillful enemy. However, by April 1945 the superbly led and combat-hardened Allied 15th Army Group, a truly multinational force, enjoyed an overwhelming numerical superiority on the ground and in the air. On the other side, Axis forces had been worn down by years of combat on many fronts; they were plagued by poor political leadership at the top as well as shortages of nearly everything needed to wage a successful defensive war. By April 1945 factors such as terrain, weather, combat experience, and able military leadership, that had for months allowed the Axis to trade space for time in Italy could no longer compensate for the simple lack of manpower, air support, and materiel. By the end of the first two weeks of the campaign both sides realized that the end of the war in Italy was in sight, and that all the Allies needed to complete the destruction of Axis forces was the skillful application of overwhelming pressure, a feat largely accomplished within ten days, by 2 May 1945.

Rhineland: 15 September 1944–21 March 1945

The Rhineland Campaign, although costly for the Allies, had clearly been ruinous for the Germans. The Germans suffered some 300,000 casualties and lost vast amounts of irreplaceable equipment. Hitler, having demanded the defense of all of the German homeland, enabled the Allies to destroy the Wehrmacht in the West between the Siegfried Line and the Rhine River. Now, the Third Reich lay virtually prostrate before Eisenhower's massed armies.

Rome-Arno: 22 January–9 September 1944

The Allied operations in Italy between January and September 1944 were essentially an infantryman's war where the outcome was decided by countless bitterly fought small unit actions waged over some of Europe's most difficult terrain under some of the worst weather conditions found anywhere during World War II.

Ryukyus: 26 March–2 July 1945

In late September 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington decided to invade Okinawa, the largest island in the Ryukyu Islands, as part of a strategy to defeat Japan. The effort was code-named Operation ICEBERG.

The capture of the Ryukyu Islands erased any hope Japanese military leaders might have held that an invasion of the home islands could be averted. Long before the firing stopped on Okinawa, engineers and construction battalions, following close on the heels of the combat forces, were transforming the island into a major base for the projected invasion of the Japanese home islands. A soldier walking back over the terrain for which he had fought so hard just weeks before might not have recognized the landscape, as hills were leveled' ravines filled' and water courses altered to make way for airstrips, highways, and ammunition dumps. The first American-built airfield on Okinawa, a 7,000-foot airstrip at Yontan, just east of the invasion beaches, was operational by 17 June. By the end of the month a total of five air bases were ready for the heavy bombers that could soften up the islands of Kyushu and Honshu for the invasion that everyone believed inevitable. Operationally, the campaign for the Ryukyus had succeeded in its mission.

Sicily Campaign: 9 July–17 August 1943

On the night of 9–10 July 1943, an Allied armada of 2,590 vessels launched one of the largest combined operations of World War II—the invasion of Sicily. Over the next thirty-eight days, half a million Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen grappled with their German and Italian counterparts for control of this rocky outwork of Hitler's "Fortress Europe." When the struggle was over, Sicily became the first piece of the Axis homeland to fall to Allied forces during World War II. More important, it served as both a base for the invasion of Italy and as a training ground for many of the officers and enlisted men who eleven months later landed on the beaches of Normandy.

Southern France: 15 August–14 September 1944

The Allied invasion of southern France in the late summer of 1944, an operation first code-named ANVIL and later DRAGOON, marked the beginning of one of the most successful but controversial campaigns of World War II. However, because it fell both geographically and chronologically between two much larger Allied efforts in northern France and Italy, both its conduct and its contributions have been largely ignored. Planned originally as a simultaneous complement to OVERLORD, the cross-Channel attack on Normandy, ANVIL actually took place over two months later, on 15 August 1944, making it appear almost an afterthought to the main Allied offensive in northern Europe. Yet the success of ANVIL and the ensuing capture of the great southern French ports of Toulon and Marseille, together with the subsequent drive north up the Rhone River valley to Lyon and Dijon, were ultimately to provide critical support to the Normandy-based armies finally moving east toward the German border.

Southern Philippines: 27 February–4 July 1945

The Southern Philippines Campaign usually is given short shrift in popular histories of World War II. The campaign, which the U.S. Army recognizes as ending on 4 July 1945, actually lasted until news of the Japanese surrender in early September. Recapturing the southern Philippines cost the Eighth Army approximately 2,100 dead and 6,990 wounded. The Japanese Thirty-Fifth Army lost vastly more. Overall, the campaign's primary objective, eradicating Japanese military power on the Philippine Islands, was achieved quickly and, compared to other campaigns in the Pacific, at relatively little cost.

Tunisia: 17 November 1942–13 May 1943

Victory at Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers gave the United States Army and its British ally solid toeholds in the western Mediterranean Theater of Operations. But it offered no guarantee of easy access to Italy or southern Europe, or even to the eastern end of the Mediterranean, where the British desperately needed assistance to secure Egypt and strategic resources in the Near East. The sudden entrance of American forces during 8–11 November 1942 created an awkward deployment in which two pairs of opposing armies fought in North Africa, one in Tunisia, the other in Libya. Neither Axis nor Allies found any satisfaction in the situation; much fighting remained before either adversary could consider North Africa secure.

If American commanders and troops thought their brief combat experience in French Morocco and Algeria in November 1942 was adequate preparation to face hardened Axis units in a lengthy campaign, the fighting in Tunisia brought about a harsh reappraisal. With few exceptions, French units in North Africa had been more intent on upholding national honor than inflicting casualties and damage; those that offered determined resistance were at a marked disadvantage in terms of weapons, equipment, supplies, and numbers. In Tunisia, however, American soldiers found themselves faced with well-trained, battle-tested units skillfully using the most advanced weapons and innovative combined arms tactics repeatedly to frustrate Allied plans. The result was painful to Army units involved and a shock to the American public: five months of almost continuous setbacks with commensurably high casualties.

Western Pacific: 15 June 1944–2 September 1945

Victory in the Western Pacific Campaign made the continued American advance across the Pacific certain. Japan's southern flank now lay wide open, and after the Battle of the Philippine Sea the Japanese no longer had the naval air strength to counter American aircraft carrier task forces. United States Army Air Forces and Navy task forces had won the bases that would allow them to sever Japan's link to the East Indies oil fields, interdict its supply lines to China, and attack the Japanese home islands themselves. Furthermore, no enemy held territory remained between American forces and the Philippines.

But these gains had not come easily. In the Marianas and Palaus the Army lost 7,791 dead and wounded, the Marine Corps and Navy over 26,000 dead and wounded. Japanese casualties totaled more than 72,000, all but a few hundred killed. The obvious advantage of the air bases and anchorages gained on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam justified the Marianas invasion, but the minor strategic value of the Palaus left troubling questions about overall American decision making in the Pacific. Intended to support subsequent operations against the Philippines, the airfields and ports of Peleliu and Angaur ultimately proved less than essential.

A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II

A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II highlights the major ground force campaigns during the six years of the war. This brochure was prepared at the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Wayne M. Dzwonchyk (Europe) and John Ray Skates (Pacific).

Defense of the Americas

The history of the American theater encompassed no great battles, and the Army played no significant part in its few skirmishes. Thus it passed almost unnoticed. In a sense, however, this campaign was the most important of the entire war, for success in securing the nation proper from external attack was the foundation for Allied victory. Secure from outside attack, the nation built armed forces capable of global action and developed, manufactured, and distributed the modern weapons to equip both these forces and those of many of America's Allies.

Mobilization in World War II.

Despite all of the problems associated with mobilization during World War II, the achievement was remarkable. Exploiting the happy conjunction of circumstances offered by idle resources, the protection provided by its insular position, and the heroic resistance of its Allies, the United States developed, produced, and delivered a flood of equipment and supplies for its own and Allied troops. The country showed a preeminent capability for what R. Elberton Smith characterized as "technological warfare on a global scale" and furnished the Allies with decisive economic and industrial power.

The filescontains a text transcript of all recognizable text embedded into the graphic image of each page of each document, creating a searchable finding aid.

1,216 pages of United States Army official campaign histories, composed of text, 220 photos, 134 maps, and 35 hand-drawn illustrations,.

History compiled by the Center of Military History United States Army, covering World War II campaigns in Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, The Pacific and Asia. The volumes published in 1992, cover campaign backgrounds, strategic settings, operations, and provides analysis.

World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. Highly relevant today, World War II has much to teach us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations. World War II was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over several diverse theaters of operation for approximately six years. This series of campaign studies highlighting those struggles are designed to introduce military feats from World War II.

Thirty-eight condensed histories ranging from 20 to 56 pages each. Campaign books include:

Aleutian Islands: 3 June 1942–24 August 1943

Algeria–French Morocco: 8 November 1942–11 November 1942

Anzio: 22 January–24 May 1944

Ardennes-Alsace: 16 December 1944–25 January 1945

Bismarck Archipelago: 15 December 1943–27 November 1944

Burma, 1942: 7 December 1941-26 May 1942

Central Europe 22 March–11 May 1945

Central Pacific: 7 December 1941-6 December 1943

Central Burma: 29 January–15 July 1945

China Defensive: 4 July 1942–4 May 1945

China Offensive: 5 May–2 September 1945

East Indies: 1 January–22 July 1942

Eastern Mandates: 31 January–14 June 1944

Egypt-Libya: 11 June 1942–12 February 1943

Guadalcanal: 7 August 1942–21 February 1943

India-Burma: 2 April 1942–28 January 1945

Leyte: 17 October 1944 1 July 1945

Luzon: 15 December 1944–4 July 1945

Naples-Foggia: 9 September 1943–21 January 1944

New Guinea: 24 January 1943–31 December 1944

Normandy: 6 June–24 July 1944

North Apennines: 10 September 1944–4 April 1945

Northern France: 25 July–14 September 1944

Northern Solomons: 22 February 1943–21 November 1944

Papua: 23 July 1942–23 January 1943

Philippine Islands: 7 December 1941–10 May 1942

Po Valley: 5 April–8 May 1945

Rhineland: 15 September 1944–21 March 1945

Rome-Arno: 22 January–9 September 1944

Ryukyus: 26 March–2 July 1945

Sicily Campaign: 9 July–17 August 1943

Southern France: 15 August–14 September 1944

Southern Philippines: 27 February–4 July 1945

Tunisia: 17 November 1942–13 May 1943

Western Pacific: 15 June 1944–2 September 1945

Plus "A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II","Defense of the Americas" and "Mobilization in World War II."

Aleutian Islands: 3 June 1942–24 August 1943

Protruding in a long, sweeping curve for more than a thousand miles westward from the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula, the Aleutians provided a natural avenue of approach between Japan and the United States. Japanese concern for the defense of the northern Pacific increased when sixteen U.S. B-25 bombers, led by Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, took off from the carrier Hornet and bombed Tokyo on 18 April 1942. Unsure of where the American raid originated, but suspicious that it could have been from a secret base in the western Aleutians, the Imperial High Command began to take an active interest in capturing the island chain.

The Aleutians first appeared as a Japanese objective in a plan prepared under the direction of one of Japan's most able commanders, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. An attack on the Aleutians in early June 1942, Yamamoto believed, would draw the U.S. fleet north to challenge his forces.

Algeria–French Morocco: 8 November 1942–11 November 1942

Events bringing the United States Army to North Africa had begun more than a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. For both the Axis and the Allies, the Mediterranean Sea area was one of uncertain priority. On the Axis side, the location of Italy made obvious Rome's interest in the region. But the stronger German partner pursued interests hundreds of miles north. A similar division of emphasis characterized the Allies. To the British the Mediterranean Sea was the vital link between the home islands and long-held Asian possessions as well as Middle Eastern oil fields. To the Americans, however, the area had never been one of vital national interest and was not seen as the best route to Berlin. But the fall of France in June 1940 had also brought a new dimension to the region. The surrender of Paris left 120,000 French troops in West and North Africa and much of the French fleet in Atlantic and Mediterranean ports. Both the Axis and Allies saw overseas French forces as the decisive advantage that would allow them to achieve their contradictory objectives in the Mediterranean.

Anzio: 22 January–24 May 1944

The four months of this campaign would see some of the most savage fighting of World War II.

Following the successful Allied landings at Calabria, Taranto, and Salerno in early September 1943 and the unconditional surrender of Italy that same month, German forces had quickly disarmed their former allies and begun a slow, fighting withdrawal to the north. Defending two hastily prepared, fortified belts stretching from coast to coast, the Germans significantly slowed the Allied advance before settling into the Gustav Line, a third, more formidable and sophisticated defensive belt of interlocking positions on the high ground along the peninsula's narrowest point.

During the four months of the Anzio Campaign the Allied VI Corps suffered over 29,200 combat casualties (4,400 killed, 18,000 wounded, 6,800 prisoners or missing) and 37,000 noncombat casualties. Two-thirds of these losses, amounting to 17 percent of VI Corps' effective strength, were inflicted between the initial landings and the end of the German counteroffensive on 4 March. Of the combat casualties, 16,200 were Americans (2,800 killed, 11,000 wounded, 2,400 prisoners or missing) as were 26,000 of the Allied noncombat casualties. German combat losses, suffered wholly by the Fourteenth Army, were estimated at 27,500 (5,500 killed, 17,500 wounded, and 4,500 prisoners or missing), figures very similar to Allied losses.

The Anzio Campaign continues to be controversial, just as it was during its planning and implementation stages. The operation, according to U.S. Army Center of Military History historian Clayton D. Laurie, clearly failed in its immediate objectives of outflanking the Gustav Line, restoring mobility to the Italian campaign, and speeding the capture of Rome.

Yet the campaign did accomplish several goals. The presence of a significant Allied force behind the German main line of resistance, uncomfortably close to Rome, represented a constant threat. The Germans could not ignore Anzio and were forced into a response, thereby surrendering the initiative in Italy to the Allies. The 135,000 troops of the Fourteenth Army surrounding Anzio could not be moved elsewhere, nor could they be used to make the already formidable Gustav Line virtually impregnable.

Ardennes-Alsace: 16 December 1944–25 January 1945

In August 1944, while his armies were being destroyed in Normandy, Hitler secretly put in motion actions to build a large reserve force, forbidding its use to bolster Germany's beleaguered defenses. To provide the needed manpower, he trimmed existing military forces and conscripted youths, the unfit, and old men previously untouched for military service during World War II.

In September Hitler named the port of Antwerp, Belgium, as the objective. Selecting the Eifel region as a staging area, Hitler intended to mass twenty-five divisions for an attack through the thinly held Ardennes Forest area of southern Belgium and Luxembourg. Once the Meuse River was reached and crossed, these forces would swing northwest some 60 miles to envelop the port of Antwerp. The maneuver was designed to sever the already stretched Allied supply lines in the north and to encircle and destroy a third of the Allies' ground forces. If successful, Hitler believed that the offensive could smash the Allied coalition, or at least greatly cripple its ground combat capabilities, leaving him free to focus on the Russians at his back door.

Bismarck Archipelago: 15 December 1943–27 November 1944

By the close of 1943, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand had stopped the Japanese juggernaut in the Pacific. To put the Japanese on the defensive, within the framework of the global strategy adopted by American and British leaders, the Allies initiated offensive operations along two mutually supporting lines of advance. Admiral Chester Nimitz, who commanded operations in the Central Pacific, invaded the Gilbert Islands in the Allied drive toward Japan, while General Douglas MacArthur, commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, initiated a series of amphibious assault operations along the New Guinea coast. These operations were the first steps in his drive to return to the Philippines, a pledge he had made when he left the islands in 1942.

Before MacArthur could begin operations against the Philippines, he needed to capture the Bismarck Archipelago, a group of islands off the New Guinea coast. Continued enemy control of the region would otherwise jeopardize his campaign. The struggle for these islands, New Britain, New Ireland, the Admiralties, and several smaller islands, was officially designated as the Bismarck Archipelago Campaign.

Burma, 1942: 7 December 1941-26 May 1942

Early in 1942 Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell arrived in the Far East to command American forces in what became the China-Burma-India theater and to serve as chief of staff and principal adviser to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the political and military leader of Nationalist China. Stilwell's mission was to improve the efficiency of Chiang's army, which had been fighting the Japanese since 1937, and to keep China in the war. But the Japanese conquest of Burma later in 1942 cut the last overland supply route to China and frustrated Stilwell's plans.

The loss of Burma was a serious blow to the Allies. It completed the blockade of China, and without Allied aid, China's ability to oppose the Japanese invasion was extremely limited. Militarily, according to U.S. Army Center of Military History historian Clayton D. Laurie, the Allied failure in Burma can be attributed to unpreparedness on the part of the British to meet the Japanese invasion and the failure of the Chinese to assist wholeheartedly in the defense.

Central Burma: 29 January–15 July 1945

The final campaign for clearing Japanese invaders from Burma was well under way by the start of 1945 with a desperate enemy grudgingly giving ground before a more powerful Allied force composed of units the majority of which were Chinese and Indian veterans. Their Japanese opponent, still a formidable challenge, was a ruthless and bold soldier who obediently fought and marched until he died or killed himself.

Central Europe 22 March–11 May 1945

By the beginning of the Central Europe Campaign of World War II, Allied victory in Europe was inevitable. Having gambled his future ability to defend Germany on the Ardennes offensive and lost, Hitler had no real strength left to stop the powerful Allied armies. Yet Hitler forced the Allies to fight, often bitterly, for final victory. Even when the hopelessness of the German situation became obvious to his most loyal subordinates, Hitler refused to admit defeat. Only when Soviet artillery was falling around his Berlin headquarters bunker did the German Fuehrer begin to perceive the final outcome of his megalomaniacal crusade.

Central Pacific: 7 December 1941-6 December 1943

The Central Pacific Campaign, one of the longest in World War II, had a clear and definite beginning with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Its termination on 6 December 1943, however, was apparently determined more by a desire to make it a tidy two-year campaign than by the attainment of any particular strategic objective. The campaign was mainly defensive, although the Battle of Midway and Operation GALVANIC were notable offensive operations. The former finally brought the Japanese offensive to a halt, and the latter marked the opening of the American drive across the Pacific that would eventually end World War II.

Most of the Central Pacific Campaign took place in Micronesia, an area of the globe larger than the continental United States, where a multitude of islands lie scattered about a vast expanse of ocean. Clustered into four major groups, these Pacific islands have a landmass of about 1,200 square miles, an area somewhat larger than the state of Rhode Island. The most easterly of the four island groups are the Gilberts, low-lying coral atolls, straddling the equator just west of the international date line. North and west of the Gilberts are the Marshall Islands, a double chain of atolls, reefs, and islets, most of which rise only a few feet above sea level. Stretching almost due west from the Marshalls are the 550 tiny islands of the Caroline group. The Marianas lie just north of the Carolines in a 400-mile north-south chain.

China Defensive: 4 July 1942–4 May 1945

The China theater posed unique problems for the U.S. military. Unlike Western Europe, where key partners employed comparable resources, operations in China involved only a handful of U.S. ground and logistical units in support of huge Chinese armies. Moreover, civil strife in China, which long predated the outbreak of World War II and was, at best, only obscured by the struggle with Imperial Japan, made any conventional approach to American support unrealistic. Within both the Nationalist Chinese and Red Chinese armies, internal politics and military reform were inextricably linked, and any hope of creating an effective and conventional Chinese military while temporarily shelving China's internal political problems was unrealistic.

The U.S. Army's main role in China was to keep China in the war through the provision of advice and materiel assistance. As long as China stayed in the war, hundreds of thousands of Imperial Japanese Army soldiers could be tied down on the Asian mainland. Success was thus measured differently than in most theaters. How well both General Stilwell and General Wedemeyer persuaded the theater commander-in-chief, Generalissimo Chiang, to support U.S. strategic goals, and how effectively U.S. training and materiel support could build selected Chinese Army divisions into modern tactical units, capable of standing up to Japanese adversaries, were secondary objectives. What mattered most was simply keeping China in the war against Japan.

China Offensive: 5 May–2 September 1945

As victory in Europe appeared increasingly inevitable in the early months of 1945, the Allies began to focus greater military resources on the war against Japan. Throughout the spring of 1945 Allied forces drove the Japanese from Burma and dislodged Japanese forces from key islands in the central and southwest Pacific. With its sea power shattered and its air power outmatched, Japan's only remaining resource was its relatively intact ground force. Although the land campaigns in Burma and the Philippines had been disastrous for the engaged Japanese forces, those and other outlying garrisons represented only a small percent of its ground troops. The bulk of Japan's army of over two million men was on the mainland of Asia, primarily in China.

On 14 February 1945, General Wedemeyer submitted his plan for the Chinese offensive to Chiang Kai-shek, who immediately approved it. The plan had four phases: the capture of the Liuchow-Nanning area; the consolidation of the captured area; the concentration of forces needed for an advance to the Hong Kong–Canton coastal region; and an offensive operation to capture Hong Kong and Canton. The Joint Chiefs of Staff eventually approved the plan on 20 April.

East Indies: 1 January–22 July 1942

The experience of 2d Battalion, 131st Field Artillery, and the loss of thousands of Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen in the East Indies stands as a reminder of Allied unpreparedness in the Pacific in 1941.

Eastern Mandates: 31 January–14 June 1944

One of the island groups targeted for invasion in the Joint Chiefs' plan was the Eastern Mandates, better known as the Marshall Islands. Under German control from the late 1890s through the end of World War I, the Marshalls had been assigned to the Japanese as mandates in accord with Article 22 of the League of Nations Charter.

Egypt-Libya: 11 June 1942–12 February 1943

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the British had been fighting German and Italian armies in the Western Desert of Egypt and Libya for over a year. In countering an Italian offensive in 1940, the British had at first enjoyed great success. In 1941, however, when German forces entered the theater in support of their Italian ally, the British suffered severe reversals, eventually losing nearly all their hard-won gains in North Africa.

The Egypt-Libya Campaign was one of the smaller, less well known U.S. Army campaigns of World War II. Its significance, however, cannot be measured simply by counting Army forces involved. The campaign made a major contribution to Allied success in World War II by laying a firm foundation of Anglo-American cooperation.

Guadalcanal: 7 August 1942–21 February 1943

Victory on Guadalcanal brought important strategic gains to the Americans and their Pacific allies but at high cost. Combined with the American-Australian victory at Buna on New Guinea, success in the Solomons turned back the Japanese drive toward Australia and staked out a strong base from which to continue attacks against Japanese forces,

India-Burma: 2 April 1942–28 January 1945

"Historians have found it fashionable to characterize the CBI as a forgotten theater, low in the Allied list of priorities," according to U.S. Army Center of Military historian David W. Hogan. "To be sure, the European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters all enjoyed greater access to scarce manpower and material than the CBI, which had to cope with an extended line of supply back to the United States. Only a few American combat troops served in China, Burma, or India. Yet one can hardly call the CBI an ignored theater. It occupied a prominent place in Allied councils, as Americans sought an early Allied commitment to reopening China's lifeline so that China could tie down massive numbers of Japanese troops and serve as a base for air, naval, and eventually amphibious operations against the Japanese home islands."

Leyte: 17 October 1944 1 July 1945

By the summer of 1944, American forces had fought their way across the Pacific on two lines of attack to reach a point 300 miles southeast of Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippines. In the Central Pacific, forces under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean areas, had island-hopped through the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and the Carolines. More than 1,000 miles to the south, Allied forces under General Douglas MacArthur, commanding the Southwest Pacific area, had blocked the Japanese thrust toward Australia, and then recaptured the Solomons and New Guinea and many of its outlying islands, isolating the huge Japanese base at Rabaul.

These victories brought American forces to the inner defensive line of the Japanese Empire, and in the summer of 1944 they pushed through that barrier to take the Marianas, the Palaus, and Morotai. With the construction of airfields in the Marianas, US. Army Air Forces were within striking distance of the Japanese home islands for the first time during the war. Yet, despite an unbroken series of defeats during two years of fighting, the Japanese showed no inclination to end the war. As American forces closed on Japan, they thus faced the most formidable outposts of the Japanese Empire: the Philippines, Formosa, and Okinawa.

The campaign for Leyte proved the first and most decisive operation in the American reconquest of the Philippines. The Japanese invested heavily in Leyte, and lost. The campaign cost their army four divisions and several separate combat units, while their navy lost twenty-six major warships, and forty-six large transports and merchantmen. The struggle also reduced Japanese land-based air capability in the Philippines by more than 50 percent, forcing them to depend on suicidal kamikaze pilots.

Luzon: 15 December 1944–4 July 1945

"The Philippine theater of operations is the locus of victory or defeat," argued General Douglas MacArthur, as Japanese planes strafed and bombed key installations around Manila on 8 December 1941. Although overwhelming Japanese strength ultimately forced the United States to relinquish the Philippines, MacArthur began planning his return almost immediately from bases in Australia. Throughout the long campaign to push the Japanese out of their Pacific bastions, these islands remained his crucial objective. "The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines...for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary object of which is the relief of the Philippines," MacArthur said when he took over as Allied commander in the Southwest Pacific. "I came through and I shall return." As the Pacific campaign dragged on, MacArthur never strayed far from that goal, and every move he made was aimed ultimately at recapturing the lost archipelago.

Naples-Foggia: 9 September 1943–21 January 1944

The Allied goals, established before the invasion of Italy, were to gain control of the Mediterranean, keep pressure on the Germans while building for the cross-Channel attack, and force Italy to withdraw from the war. All agreed that bases in Italy would provide support for the air war against German sources of supply in the Balkans and the German industrial heartland itself. These sound strategic goals were valid in 1943 and have stood the test of time. By late August, the Italian government had decided to withdraw from the war and break relations with Germany. The fall of Sicily had enhanced Allied control of the Mediterranean but had not assured it. Prior to the invasion of Italy, therefore, the Allied goals were far from being totally satisfied, and an eager world watched as the Allies launched first Operation BAYTOWN and then Operation AVALANCHE to invade the European continent.

New Guinea: 24 January 1943–31 December 1944

The campaign on New Guinea is all but forgotten except by those who served there. Battles with names like Tarawa, Saipan, and Iwo Jima overshadow it. Yet Allied operations in New Guinea were essential to the U.S. Navy's drive across the Central Pacific and to the U.S. Army's liberation of the Philippine Islands from Japanese occupation. The remorseless Allied advance along the northern New Guinea coastline toward the Philippines forced the Japanese to divert precious ships, planes, and men who might otherwise have reinforced their crumbling Central Pacific front.

In January 1943 the Allied and the Japanese forces facing each other on New Guinea were like two battered heavyweights. Round one had gone to the Americans and Australians who had ejected the Japanese from Papua, New Guinea. After three months of unimaginative frontal attacks had overcome a well-entrenched foe, General Douglas MacArthur, the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) commander, had his airstrip and staging base at Buna on the north coast. It was expensive real estate. About 13,000 Japanese troops perished during the terrible fighting, but Allied casualties were also heavy; 8,500 men fell in battle (5,698 of them Australians) and 27,000 cases of malaria were reported, mainly because of shortages of medical supplies.

Normandy: 6 June–24 July 1944

A great invasion force stood off the Normandy coast of France as dawn broke on 6 June 1944: 9 battleships, 23 cruisers, 104 destroyers, and 71 large landing craft of various descriptions as well as troop transports, mine sweepers, and merchantmen—in all, nearly 5,000 ships of every type, the largest armada ever assembled. The naval bombardment that began at 0550 that morning detonated large minefields along the shoreline and destroyed a number of the enemy's defensive positions. To one correspondent, reporting from the deck of the cruiser HMS Hillary, it sounded like "the rhythmic beating of a gigantic drum" all along the coast. In the hours following the bombardment, more than 100,000 fighting men swept ashore to begin one of the epic assaults of history, a "mighty endeavor," as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it to the American people, "to preserve. . . our civilization and to set free a suffering humanity."

North Apennines: 10 September 1944–4 April 1945

The northern Apennines fighting was the penultimate campaign in the Italian theater. Although the Allies steadily lost divisions, materiel, and shipping to operations elsewhere, which diminished their capabilities, their offensives prevented the Axis from substantially reinforcing other fronts with troops from Italy. Yet the transfer of units from Fifth and Eighth Armies for use in northwest Europe, southern France, and Greece, both after the capture of Rome and during the North Apennines Campaign itself, left Allied commanders with just enough troops to hold Axis forces in Italy but without sufficient forces to destroy the enemy or to end the campaign.

Northern France: 25 July–14 September 1944

As July 1944 entered its final week, Allied forces in Normandy faced, at least on the surface, a most discouraging situation. In the east, near Caen, the British and Canadians were making little progress against fierce German resistance. In the west, American troops were bogged down in the Norman hedgerows. These massive, square walls of earth, five feet high and topped by hedges, had been used by local farmers over the centuries to divide their fields and protect their crops and cattle from strong ocean winds. The Germans had turned these embankments into fortresses, canalizing the American advance into narrow channels, which were easily covered by antitank weapons and machine guns. The stubborn defenders were also aided by some of the worst weather seen in Normandy since the turn of the century, as incessant downpours turned country lanes into rivers of mud. By 25 July, the size of the Allied beachhead had not even come close to the dimensions that pre–D-day planners had anticipated, and the slow progress revived fears in the Allied camp of a return to the static warfare of World War I. Few would have believed that, in the space of a month and a half, Allied armies would stand triumphant at the German border.

Northern Solomons: 22 February 1943–21 November 1944

The Northern Solomons is one of the more unheralded of the U.S. Army campaigns of World War II, largely overshadowed by its predecessor, Guadalcanal, and by its more publicized successor, Leyte. Furthermore, with hindsight the campaign for the northern Solomon Islands might be described simply as bringing to bear preponderant American strength on isolated Japanese positions. Such a summary does describe accurately what American strategy skillfully achieved through sustained joint operations: the isolation and subsequent defeat in detail of Japanese forces.

Papua: 23 July 1942–23 January 1943

The United States Army learned much from the Papua Campaign but at a high cost. Allied losses totaled 8,546 killed and wounded. Of those, the 32d Division lost 687 killed in action and 2,161 wounded or lost from other causes. The lack of leaders experienced in jungle fighting accounted in part for these losses. Because the campaign was the Army's first in a world war tropical theater, everyone involved had to learn while under fire. The last combat experience of the Allied leaders had ended in 1918. The Australians had spent recent years in the Middle East. Only General MacArthur, with years of duty in the Philippines, brought to the campaign any familiarity with jungle fighting, but as theater commander he exercised leadership far from the front. The necessarily trial-and-error tactical approach of the Allies in the early stages of the campaign inevitably delayed the victory.

Philippine Islands: 7 December 1941–10 May 1942

The valiant defense of the Philippines had several important consequences. It delayed the Japanese timetable for the conquest of south Asia, causing them to expend far more manpower and materiel resources than anticipated. Probably of equal importance, the determined resistance against overwhelming odds became a symbol of hope for the United States in the early, bleak days of the war. When surrender came, the image of the self-proclaimed "Battling Bastards of Bataan" inspired the Allied troops to honor such sacrifices by vowing to retake the islands. MacArthur himself became an important symbol of America's pledge to return to the Far East.

Po Valley: 5 April–8 May 1945

For the Allied armies in Italy, the Po Valley offensive climaxed the long and bloody Italian campaign. When the spring offensive opened, it initially appeared that its course might continue the pattern of the previous months and battles in Italy, becoming another slow, arduous advance over rugged terrain, in poor weather, against a determined, well-entrenched, and skillful enemy. However, by April 1945 the superbly led and combat-hardened Allied 15th Army Group, a truly multinational force, enjoyed an overwhelming numerical superiority on the ground and in the air. On the other side, Axis forces had been worn down by years of combat on many fronts; they were plagued by poor political leadership at the top as well as shortages of nearly everything needed to wage a successful defensive war. By April 1945 factors such as terrain, weather, combat experience, and able military leadership, that had for months allowed the Axis to trade space for time in Italy could no longer compensate for the simple lack of manpower, air support, and materiel. By the end of the first two weeks of the campaign both sides realized that the end of the war in Italy was in sight, and that all the Allies needed to complete the destruction of Axis forces was the skillful application of overwhelming pressure, a feat largely accomplished within ten days, by 2 May 1945.

Rhineland: 15 September 1944–21 March 1945

The Rhineland Campaign, although costly for the Allies, had clearly been ruinous for the Germans. The Germans suffered some 300,000 casualties and lost vast amounts of irreplaceable equipment. Hitler, having demanded the defense of all of the German homeland, enabled the Allies to destroy the Wehrmacht in the West between the Siegfried Line and the Rhine River. Now, the Third Reich lay virtually prostrate before Eisenhower's massed armies.

Rome-Arno: 22 January–9 September 1944

The Allied operations in Italy between January and September 1944 were essentially an infantryman's war where the outcome was decided by countless bitterly fought small unit actions waged over some of Europe's most difficult terrain under some of the worst weather conditions found anywhere during World War II.

Ryukyus: 26 March–2 July 1945

In late September 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington decided to invade Okinawa, the largest island in the Ryukyu Islands, as part of a strategy to defeat Japan. The effort was code-named Operation ICEBERG.

The capture of the Ryukyu Islands erased any hope Japanese military leaders might have held that an invasion of the home islands could be averted. Long before the firing stopped on Okinawa, engineers and construction battalions, following close on the heels of the combat forces, were transforming the island into a major base for the projected invasion of the Japanese home islands. A soldier walking back over the terrain for which he had fought so hard just weeks before might not have recognized the landscape, as hills were leveled' ravines filled' and water courses altered to make way for airstrips, highways, and ammunition dumps. The first American-built airfield on Okinawa, a 7,000-foot airstrip at Yontan, just east of the invasion beaches, was operational by 17 June. By the end of the month a total of five air bases were ready for the heavy bombers that could soften up the islands of Kyushu and Honshu for the invasion that everyone believed inevitable. Operationally, the campaign for the Ryukyus had succeeded in its mission.

Sicily Campaign: 9 July–17 August 1943

On the night of 9–10 July 1943, an Allied armada of 2,590 vessels launched one of the largest combined operations of World War II—the invasion of Sicily. Over the next thirty-eight days, half a million Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen grappled with their German and Italian counterparts for control of this rocky outwork of Hitler's "Fortress Europe." When the struggle was over, Sicily became the first piece of the Axis homeland to fall to Allied forces during World War II. More important, it served as both a base for the invasion of Italy and as a training ground for many of the officers and enlisted men who eleven months later landed on the beaches of Normandy.

Southern France: 15 August–14 September 1944

The Allied invasion of southern France in the late summer of 1944, an operation first code-named ANVIL and later DRAGOON, marked the beginning of one of the most successful but controversial campaigns of World War II. However, because it fell both geographically and chronologically between two much larger Allied efforts in northern France and Italy, both its conduct and its contributions have been largely ignored. Planned originally as a simultaneous complement to OVERLORD, the cross-Channel attack on Normandy, ANVIL actually took place over two months later, on 15 August 1944, making it appear almost an afterthought to the main Allied offensive in northern Europe. Yet the success of ANVIL and the ensuing capture of the great southern French ports of Toulon and Marseille, together with the subsequent drive north up the Rhone River valley to Lyon and Dijon, were ultimately to provide critical support to the Normandy-based armies finally moving east toward the German border.

Southern Philippines: 27 February–4 July 1945

The Southern Philippines Campaign usually is given short shrift in popular histories of World War II. The campaign, which the U.S. Army recognizes as ending on 4 July 1945, actually lasted until news of the Japanese surrender in early September. Recapturing the southern Philippines cost the Eighth Army approximately 2,100 dead and 6,990 wounded. The Japanese Thirty-Fifth Army lost vastly more. Overall, the campaign's primary objective, eradicating Japanese military power on the Philippine Islands, was achieved quickly and, compared to other campaigns in the Pacific, at relatively little cost.

Tunisia: 17 November 1942–13 May 1943

Victory at Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers gave the United States Army and its British ally solid toeholds in the western Mediterranean Theater of Operations. But it offered no guarantee of easy access to Italy or southern Europe, or even to the eastern end of the Mediterranean, where the British desperately needed assistance to secure Egypt and strategic resources in the Near East. The sudden entrance of American forces during 8–11 November 1942 created an awkward deployment in which two pairs of opposing armies fought in North Africa, one in Tunisia, the other in Libya. Neither Axis nor Allies found any satisfaction in the situation; much fighting remained before either adversary could consider North Africa secure.

If American commanders and troops thought their brief combat experience in French Morocco and Algeria in November 1942 was adequate preparation to face hardened Axis units in a lengthy campaign, the fighting in Tunisia brought about a harsh reappraisal. With few exceptions, French units in North Africa had been more intent on upholding national honor than inflicting casualties and damage; those that offered determined resistance were at a marked disadvantage in terms of weapons, equipment, supplies, and numbers. In Tunisia, however, American soldiers found themselves faced with well-trained, battle-tested units skillfully using the most advanced weapons and innovative combined arms tactics repeatedly to frustrate Allied plans. The result was painful to Army units involved and a shock to the American public: five months of almost continuous setbacks with commensurably high casualties.

Western Pacific: 15 June 1944–2 September 1945

Victory in the Western Pacific Campaign made the continued American advance across the Pacific certain. Japan's southern flank now lay wide open, and after the Battle of the Philippine Sea the Japanese no longer had the naval air strength to counter American aircraft carrier task forces. United States Army Air Forces and Navy task forces had won the bases that would allow them to sever Japan's link to the East Indies oil fields, interdict its supply lines to China, and attack the Japanese home islands themselves. Furthermore, no enemy held territory remained between American forces and the Philippines.

But these gains had not come easily. In the Marianas and Palaus the Army lost 7,791 dead and wounded, the Marine Corps and Navy over 26,000 dead and wounded. Japanese casualties totaled more than 72,000, all but a few hundred killed. The obvious advantage of the air bases and anchorages gained on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam justified the Marianas invasion, but the minor strategic value of the Palaus left troubling questions about overall American decision making in the Pacific. Intended to support subsequent operations against the Philippines, the airfields and ports of Peleliu and Angaur ultimately proved less than essential.

A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II

A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II highlights the major ground force campaigns during the six years of the war. This brochure was prepared at the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Wayne M. Dzwonchyk (Europe) and John Ray Skates (Pacific).

Defense of the Americas

The history of the American theater encompassed no great battles, and the Army played no significant part in its few skirmishes. Thus it passed almost unnoticed. In a sense, however, this campaign was the most important of the entire war, for success in securing the nation proper from external attack was the foundation for Allied victory. Secure from outside attack, the nation built armed forces capable of global action and developed, manufactured, and distributed the modern weapons to equip both these forces and those of many of America's Allies.

Mobilization in World War II.