Starting from:

$14.95

Home

Foreign Policy

Mexico CIA, Department of State, Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense Files

Mexico CIA, Department of State, Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense Files

Mexico CIA, Department of State, Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, Congressional, White House, and FBI Files

50,946 pages of CIA, Department of State, Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, Congressional, White House, and FBI Files covering Mexico. Files date from to 1945 to 2006.

The files contain a text transcript of all recognizable text embedded into the graphic image of each page of each document, creating a searchable finding aid. Text searches can be done across all files in the collection.

DOCUMENT SECTIONS IN THIS COLLECTION

CIA - OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES (OSS) FILES

1,206 pages of CIA files, dating from 1943 to 2001. Documents include CIA operational files, finished intelligence reports, memoranda, telegrams and background studies.

Highlights include:

A 1944 Office of Strategic Services, OSS, report "Crisis in the Mexican Sinarquista." A 1947 CIA report on Soviet objectives in Latin America. A series of memos from 1962 concerning plans for a visit by President John Kennedy to Mexico. A 1968 memo written weeks before student unrest in that country, concerning conditions in Mexico prior to a visit by Vice President Hubert Humphrey. It states that the, "political situation in Mexico is considerably more stable than in most Latin American countries. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) maintains a virtual monopoly over national and local politics. The security forces in Mexico City are experienced and effective in controlling demonstrations." Memos beginning in July 1968 concerning student unrest in Mexico City mentions the role of "international left" and Cuban influence in the unrest. Secondary mention is made of PRI fraud in local and gubernatorial elections as possible causes of the unrest. Periodic information cables give a day-by-day account of the Mexico City student unrest. A June 1974 memo concerning the kidnapping of Senator Figueroa in Guerrero finds that it was going to present the Echeverría Administration with a series of challenges to its policy concerning the Cabañas insurgency. Later intelligence reviews find that the unrest in Guerrero was partly a result of corruption and exploitation, population pressures, a shortage of good land, and the concentration on industry during the last 30 years. A June 27, 1974 report gives information about President Echeverría's orders for a military operation against Lucio Cabañas in order to gain the freedom Senator Figueroa. CIA analysis of the situation states that a successful operation would involve the death of Cabañas. An October 26, 1976 report finds that the economic outlook for Mexico is bleak. The report cites the Mexican public's lack of confidence in the government. The report finds that incoming president Lopez-Portillo would be able to do little to stop the economic spiral and his policies to counteract this problem would probably not produce the desired results.

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (DIA) FILES

211 pages of Defense Intelligence Agency files dating from January 1966 to March 1994. Highlights include:

Reports from the summer of 1968, on the use of the Mexican military during the student demonstrations in Mexico City. An April 28, 1992 DIA memo reports on the Mexico Defense Secretariat's concern about insurgent training camps in the state of Chiapas. A June 4, 1993 DIA report tells of a clash between Mexican Army forces and Mexican and Guatemalan guerillas near Ocosingo. The first documented account of Mexican discovery of an established, organized armed insurgency movement in Chiapas. The report tells of the capture of weapons, ammunition, communication equipment, and printed propaganda. The Mexican army also discovered a training camp with a city constructed of wood used for urban combat training. A January 1994 DIA memo tells of Zapatistas rebels capturing four cities in Chiapas. A January 1994 DIA memo tells of a telephone conversation between Mexican President Carlos Salinas and Guatemalan President Ramiro de León, discussing possible cooperation between the Mexican Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) and the Guatemalan Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (URNG), and the need for the two nations to cooperate on this matter. During the Chiapas insurgency, a May 11, 1994 memo tells of British soldiers providing Mexico's First Military Police Brigade with training on their base at Military Camp One in Mexico City, designed to address Mexican military shortcomings in mine warfare. A June 1, 1994 DIA memo reveals the use of Israeli-made Arava surveillance aircraft in Chiapas. The memo notes that EZLN rebels were able to fire anti-aircraft missiles at the surveillance vehicles. A November 28, 1994 DIA memo tells of the Mexican military seeking counterinsurgency training from the Chilean army. A December 5, 1994 DIA memo, concerning the revelation that the Mexican military was seeking Argentine military advisors, familiar with counterinsurgency tactics used during Argentina's 1970's Dirty War.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE KEY DOCUMENTS

A selection of 1,215 pages of key State Department documents covering issues involving Mexico.

Files date from 1960 to 1996. Includes documents from the Department of State in Washington D.C., the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, and U.S. consular offices throughout Mexico. The documents are made up of telegrams, confidential dispatches, airgrams, cables, memos, reports, intelligence notes, research memorandums, letters and State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) reports.

Topics include. Mexico/United States relations, PRI political hegemony, Mexican presidential administrations, Mexico-Cuba relations, Human rights, Mexican military, Student demonstrations, Drug policy and enforcement, The Corpus Christi Massacre of 1971, Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968, Chiapas uprising of 1994 and more.

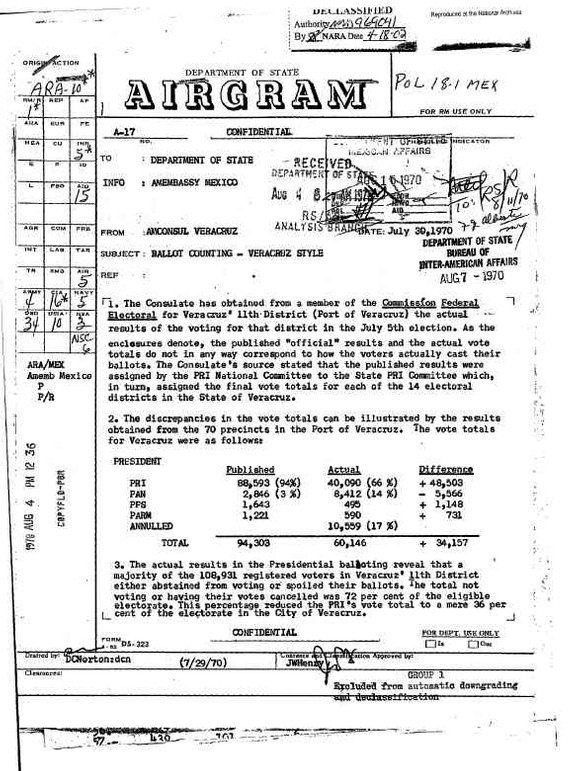

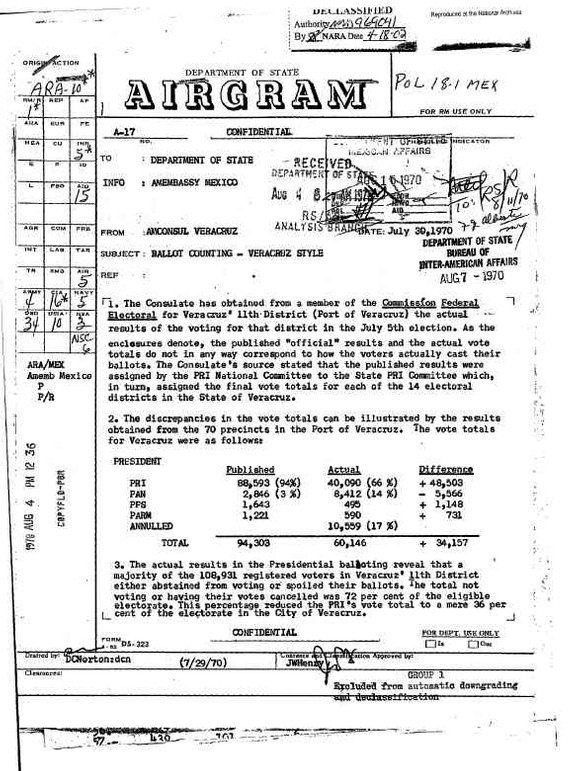

Highlights include: A July 30, 1970 airgram giving both the actual vote totals for Vaeracruz, obtained from an election official, and the "official" vote total dictated by the PRI, for the 1970 presidential election. A May 27, 1971 telegram confers Mexican Defense Secretary Hermenegildo Cuenca Díaz’s denial that there are Mexican guerrillas in Guerrero. A June 1971 memo reports on accounts of talks among politicians in Mexico on the possible removal of President Echeverría from office. A December 9, 1971 State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research analysis note concerning payment for hostages in Guerero. It finds that paying ransoms will encourage more kidnappings by rebels to obtain funds for their activities. An April 19, 1974 State Department telegram concerning the insurgency in Guerero states, "the GOM [Government of Mexico] has murdered some prisoners after extracting all information they have to give." A June 26, 1974 Mexico City embassy cable concerning Lucio Cabañas issuing a communiqué with demands for the release of Governor Ruben Figueroa. The cable mentions Mexico's preparations for a massive anti-guerilla campaign in Guerero. A February 16, 1975 airgram on human rights in Mexico states, "Given Mexico's system of one party rule, the executive branch of the Government of Mexico since circa 1930 has had certain flexibility in the degree to which it aderes to constitutional exigencies protecting human rights. As a result we would not place Mexico in the category of 'countries which are relatively exemplary in there concern for human rights'" A January 12, 1994 State Department intelligence analysis report on the Chiapas uprising, and the response of President Salinas. A May 11, 1995 memo evaluates the effects of the peso devaluation and the Zapatista uprising on the Mexican military.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE REPORTS

583 pages of reports by and created for the Department of Defense. Reports include:

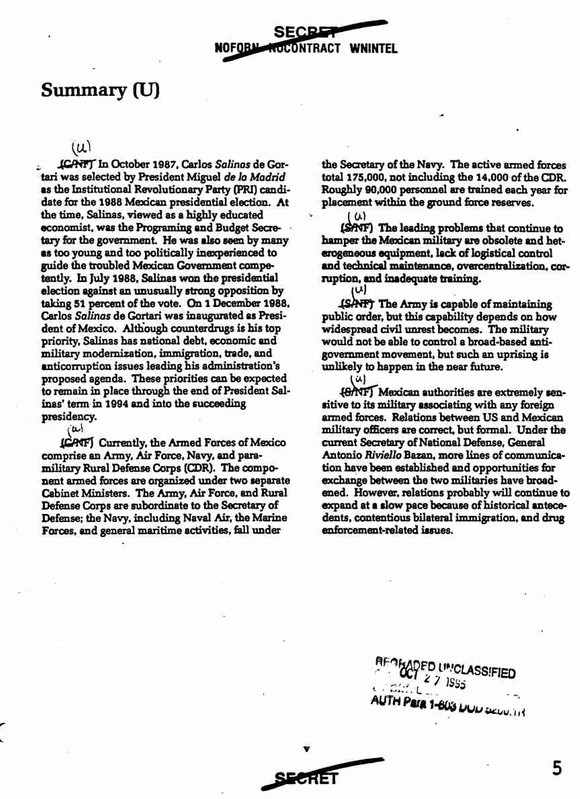

Army Country Profile Mexico Part 1 April 1993

Army Country Profile Mexico Part 2 April 1993

126 pages of a report from the Department of the Army, United States Army Intelligence and Security Command, United States Army Intelligence and Threat Analysis Center. This document discusses the mission, composition, disposition, tactics, training, logistics, capabilities, and equipment of the Mexican Armed Forces.

Part I "Ground Forces," describes the ground forces components of Mexico.

Topics include: Armed Forces Overview: Mission and Doctrine of the Armed Forces, Military Manpower and Mobilization, Order of Battle, Role of the Armed Forces in Government, Civil Military Relations, Recent Operational Experience. Ground Forces: Mission, Composition, Disposition, Personnel Strength, Strategy, Operational Art, and Doctrine, Training and Military Education, Capabilities, Ground Force Reserves, Key Personalities, Morale and Discipline, Uniforms, Insignia, and Decorations Battlefield Operating Systems: Maneuver, Special Operations Forces, Fire Support, Combat Engineers, Air Defense, Army Aviation, Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence, Logistics and Combat Service Support, Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical, Surface-to-surface Missiles, Special Weapons. Air and Naval Forces: Air Force, Navy, Composition, Disposition, Doctrine, Strength, Operations, Reserves, Marines Paramilitary Forces: Rural Defense Corps, Foreign Forces.

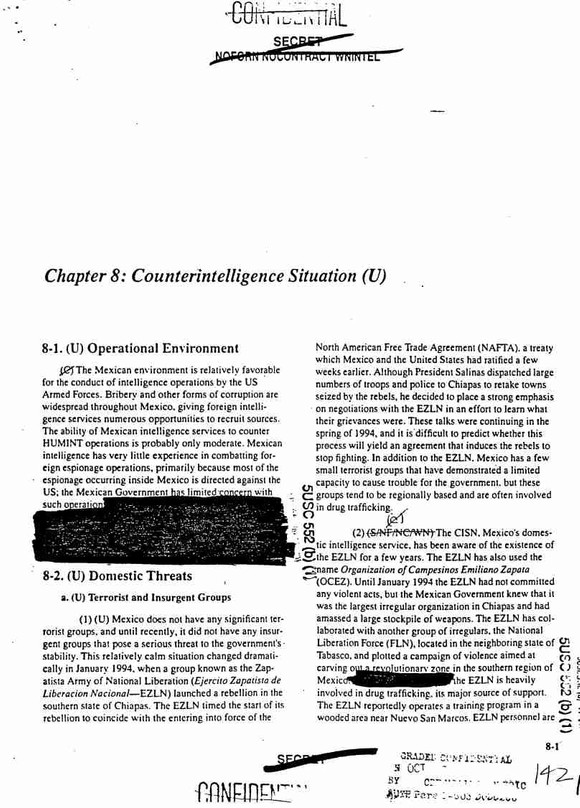

Part II “Intelligence and Security", presents analysis of the country's intelligence and security services.

The capabilities and internal organization of Mexico's major police and intelligence services are discussed. The study also presents details on the foreign intelligence presence in Mexico. Part II is intended to provide an assessment of the operational environment that would be useful for planners of US intelligence operations. Topic include: Counterintelligence Situation, Foreign Threats, and Expected Environment if US Forces Are Deployed in Mexico.

BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE: THE UNITED STATES, MEXICO, AND THE AGONY OF NATIONAL SECURITY

A 1997 Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College report. This study analyses the changing nature of U.S.-Mexican national security issues, with a focus on narcotrafficking, the growing militarization of Mexico's counterdrug and police institutions, the danger of spreading guerrilla warfare, and the prospects of political and economic instability.

THE AWAKENING: THE ZAPATISTA REVOLT AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS AND THE FUTURE OF MEXICO

A 1995 Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College study. This study examines the origins and nature of the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, the response of the Mexican government and military, and the implications for civil-military relations and the future of Mexico. It places the armed forces' reaction within the context of the institution's response to the country's accelerated transition to democracy and analyzes the implications of that democratization for the army.

The Zapatista "Social Netwar" in Mexico

The study reports on the Chiapas insurgency as a case of "netwar." "Netwar" refers to the nature of conflict in the information age, in which the protagonists depend on using a network form of organization, doctrine, strategy, and the reliance on technology such as the Internet.

Other reports include: The Mexican Armed Forces in Transition (2006). U.S. National Security Implications of Chinese Involvement in Latin America (2005). Mexico in Crisis (1995) The Mexican Military Approaches the 21st Century: Coping with a New World Order (1994).

WHITE HOUSE - EXECUTIVE BRANCH FILES

202 pages of White House and executive branch files covering Mexico, dating from 1962 to 1988. Highlights include: A 1962 White House briefing book on Mexico prepared before President Kennedy’s Visit to Mexico. Background papers prepared for a 1964 meeting between President Johnson and Mexican president Lopez Mateos. White House memos show that President Johnson was given inconsistent information about the causes of the 1968 incident at Tlatelolco. White House memos concerning President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to Mexico. Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports on Mexico's financial crisis of 1976. National Security Directives from 1987 and 1988 concerning policy toward Mexico, signed by President Ronald Reagan.

HENRY KISSINGER TELEPHONE CONVERSATION TRANSCRIPTIONS

107 pages of Henry Kissinger telephone conversation transcriptions (telcons), of conversations with links to Mexico, taking place from December 3, 1973 to December 17, 1976.

These conversations took place while Kissinger served as both Secretary of State and National Security Adviser. The telcons contain Dr. Kissinger's often-candid comments. Henry Kissinger's personality and his sense of humor and occasionally his anger, comes through in the telcons, which show the importance of personal relations and personality in his diplomacy and national security relations.

Participants include: Mexican Foreign Minister Emilio Rabasa Mishkin, Senator Jacob K. Javits, Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin, Robert O. Anderson Chairman of ARCO, Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America William Rogers, Edwin H. Yeo Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs, and Chief Justice Warren Burger.

Topics covered include travel to Mexico, Kissinger's affinity for Mexico, Mexico oil reserve discovery, Mexico-Cuba relations and the Mexican financial crisis of 1976.

The conversations between Henry Kissinger and Mexican Foreign Minister Emilio Rabasa show the strongly congenial relationship between Kissinger and Rabasa.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE CABLE ELECTRONIC RECORDS

17,635 pages of State Department cables from the State Archiving System (SAS), dating from March 1973 to December 1974, dealing with Mexico. These records are popularly known as the "State Department Cables" or the "State Department Telegrams". These records were part of the State Department Central Foreign Policy Files. The cables consist of telegrams, airgrams, and diplomatic notes. The materials relate to all aspects of American bilateral and multilateral foreign relations and routine administrative and operational activities of the Department of State and its Foreign Service posts, related to subjects involving Mexico. The telegrams convey official information about policy proposals and implementation, program activities, or personnel and post operations between the Department of State and posts abroad. After telegrams were transmitted, they were preserved in a central database that contained the text of telegrams. The State Archiving System (SAS) was the official foreign policy database that housed the Central Foreign Policy Files at the Department of State.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE BROAD COLLECTION

25,339 pages of State Department files. Documents date 1945 to 2006. This broad collection covers topics from the miniscule to the substantial, relating to Mexico at some level. The files consist of telegrams, airgrams, memoranda, correspondences, reports, diplomatic notes, and related material. The materials relate to all aspects of American bilateral and multilateral foreign relations and routine administrative and operational activities of the Department of State and its Foreign Service posts.

Documents include diplomatic message traffic about subjects outside of Mexico that was directed to U.S. diplomats in Mexico. Including:

Documents concerning human rights abuses, terrorism and political violence in Chile from 1973 to 1978.

Documents on human rights abuses in Argentina during the military dictatorship in that country from 1976 to 1983.

Documents related to the unrest in El Salvador from 1979 to 1991. Includes documents concerning allegations of human rights abuses committed by Salvadoran security forces and FMLN rebels.

Documents covering events in Guatemala from 1984 to 1995. Including State Department records on the deaths of Michael Devine, Efrain Bamaca Velasquez, Jack Shelton, Nicholas Blake and Griffin Davis, the abuse of Sister Diana Ortiz and the reported role of Guatemalan military Colonel Julio Roberto Alpirez in the deaths of Devine and Bamaca.

CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH REPORTS

678 pages of Congressional Research reports covering Mexico and United States/Mexico relations.

The 33 reports date from March 1998 to December 2006.

The Congressional Research Service is the public policy research arm of the United States Congress. As a legislative branch agency, CRS works exclusively and directly for Members of Congress, their Committees and staff on a confidential, nonpartisan basis. The CRS staff comprises nationally recognized experts in a range of issues and disciplines, including law, economics, foreign affairs, public administration, social, political sciences, and natural sciences. The breadth and depth of this expertise enables CRS staff to come together quickly to provide integrated analyses of complex issues that span multiple legislative and program areas.

The reports include: Mexico's Political History From Revolution to Alternation, 1910-2006 (2006), Mexico-United States Dialogue on Migration and Border Issues, 2001-2005 (2005), Mexico's Counter-Narcotics Efforts under Zedillo and Fox, December 1994-March 2001 (2001), Border Security: The Role of the U.S. Border Patrol (2005), Civilian Patrols Along the Border: Legal and Policy Issues (2005), Homeland Security Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Border Surveillance (2005), Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002 (2003), U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations Trends, Issues, and Implications (2005), Mexico's Importance and Multiple Relationships with the United States (2006), Mexican Drug Certification Issues U.S. Congressional Action, 1986-2001 (2002), and others.

FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES

24 pages of the Foreign Relations of the United States dealing with Mexico from 1964 to 1967. Produced by the Department of State, the Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major U.S. foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity. The series is produced by the State Department's Office of the Historian. Foreign Relations volumes contain documents from Presidential libraries, Departments of State and Defense, National Security Council, Central Intelligence Agency, Agency for International Development, and other foreign affairs agencies as well as the private papers of individuals involved in formulating U.S. foreign policy.

UNITED STATES GENERAL ACCOUNTING/ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE REPORTS

443 pages of GAO reports covering Mexico. The Government Accounting Office (GAO) was intended to be the non-partisan audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, and an agency in the Legislative Branch of the United States Government. The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 established the GAO. The GAO's legal name became the Government Accountability Office by legislation passed in 2004.

The reports include: U.S. Customs Service Concerns About Coordination and Inspection Staffing on the Southwest Border (1992), Drug Control U.S. Counterdrug Activities in Central America (1994), Mexico's Financial Crisis Origins, Awareness, Assistance, and Initial Efforts to Recover (1996), International Environment: Environmental Infrastructure Needs in the U.S.-Mexican Border Region Remain Unmet (1996), Commercial Passenger Vehicles Safety Inspection of Commercial Buses and Vans Entering the United States From Mexico (1997), Drug Control Counternarcotics Efforts in Mexico (1998), International Boundary and Water Commission U.S. Operations Need More Financial Oversight (1998), U.S. Mexico Border Despite Some Progress, Environmental Infrastructure Challenges Remain (2000), North American Free Trade Agreement Coordinated Operational Plan Needed to Ensure Mexican Trucks' Compliance With U.S. Standards (2001), and Drug Control Difficulties in Measuring Costs and Results of Transit Zone Interdiction Efforts (2002).

FBI FILES

13 pages of FBI files from 1968, concerning security at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

The files throught this collection contain a text transcript of all recognizable text embedded into the graphic image of each page of each document, creating a searchable finding aid. Text searches can be done across all files in the collection.

SUBJECT AREAS OF DEEPER COVERAGE IN THIS DOCUMENT COLLECTION

1960 Movement Against The PRI

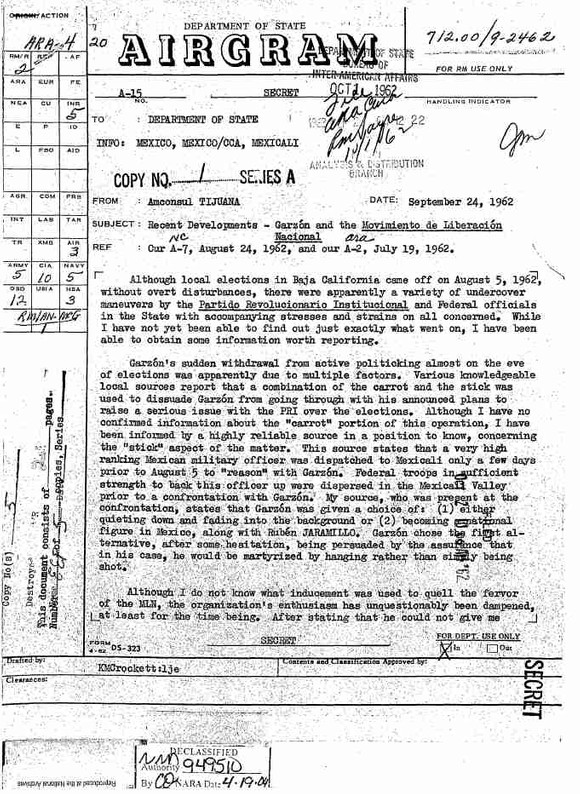

The Cuban revolution and the rise of Fidel Castro in the early 1960's had two effects on the Mexican system of governance. By taking a much less stringent stance against Cuba, the Mexican government was able to show independence from the United States. At the same time, the Cuban revolution gave a boost to the Mexican left. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) saw the resurgence of the left as a threat to its grip on political power. In 1961, former Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-40), who celebrated the revolution with Fidel Castro in Havana in July 1959, broke with the PRI and founded the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional (MLN). The MLN brought various leftist movements under a loose federation.

Documents in this set chronicle the U.S. government's monitoring of the efforts of President Adolfo López Mateos to suppress the MLN movement. The FBI referred to the MLN as a “rabidly anti-United States, pro-Cuba Communist front." Local American Consulate offices sent messages to the embassy in Mexico City on the progress of the MLN and the response of the Mateos government to repress it. The attitude of the U.S. government was that these measures were necessary to oppose the pro-Cuban, communist influenced left.

Documents show that U.S. diplomats in Mexico were at first concerned that President López Mateos did not comprehend the seriousness of the growth of the popularity of the left in Mexico. A telegram sent to the White House in 1961 by U.S. Ambassador Thomas Mann suggests linking a $400 million loan plan for Mexico, to the encouragement of the PRI government to begin a quiet program of action against the left. Department of State documents show the pressure placed on Mateos and Cárdenas to have certain candidates from the left end their political campaigns.

For example, when MLN leaders in Tijuana appeared to be backing the candidacy for state congress of Alfonso Garzón. Garzon was an agrarian leader of Liga Agraria Estata. U.S. Consul Kennedy Crockett sent a message to the State Department in Washington D.C., saying that a high-ranking Mexican military official was, "dispatched to Mexicali only a few days before the election to 'reason' with Garzón. Federal troops in sufficient strength to back this officer up were dispersed in the Mexicali Valley." Crockett's message went on to say, "My source, who was present at the confrontation, states that Garzón was given a choice of: 1 either quieting down and fading into the background or 2 becoming a national figure in Mexico, along with Rubén Jaramillo [an agrarian leader killed by the army five months earlier]. Garzón chose the first alternative, after some hesitation, being persuaded by the assurance that in his case, he would be martyrized [sic] by hanging rather than simply being shot."

1961 Visit of President John F. Kennedy to Mexico

Relations between the United States and Mexico chilled after the Bay of Pigs failure. The Mexican government criticized the United States for attempting to overthrow Cuban leader Fidel Castro. A trip by President Kennedy was seen as a chance to heal the rift between the two nations. When Mexico at a meeting of the Organization of American States (OAS) came out against certain actions against Cuba, the trip was postponed in displeasure. The State Department believed that the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) was instructed by the Soviet Union to disrupt Kennedy's planned visit. Department of State documents indicate that in response, the Mexican government arrested some Mexican communists and members of the MLN and detained them until after Kennedy’s visit.

1968 Tlatelolco Massacre

The Tlatelolco Massacre, also known as The Night of Tlatelolco (from a book title by the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska), took place on the afternoon and night of October 2, 1968, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City, ten days before the 1968 Summer Olympics celebrations in Mexico City. The death toll remains controversial: some estimates place the number of deaths in the thousands, but most sources report 200-300 deaths. Government sources say "4 Dead, 20 Wounded". The exact number of people who were arrested is also unsettled.

The massacre was preceded by months of political unrest in the Mexican capital, echoing student demonstrations and riots all over the world during 1968. The Mexican students wanted to exploit the attention focused on Mexico City for the 1968 Summer Olympics. President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, however, was determined to stop the demonstrations and, in September, he ordered the army to occupy the campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the largest university in Mexico. Students were beaten and arrested indiscriminately. Rector Javier Barros Sierra resigned in protest on September 23.

Student demonstrators were not deterred, however. The demonstrations grew in size, until, on October 2, after student strikes lasting nine weeks, 15,000 students from various universities marched through the streets of Mexico City, carrying red carnations to protest the army's occupation of the university campus. By nightfall, 5,000 students and workers, many of them with spouses and children, had congregated outside an apartment complex in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco for what was supposed to be a peaceful rally. Among their chants were México – Libertad – México – Libertad ("Mexico – Liberty – Mexico – Liberty"). Rally organizers did not attempt to call off the protest when they noticed an increased military presence in the area.

The massacre began at sunset when police and military forces, equipped with armored cars and tanks, surrounded the square and began firing live rounds into the crowd, hitting not only the protestors, but also other people who were present for reasons unrelated to the demonstration. Demonstrators and passersby alike, including children, were caught in the fire; soon, mounds of bodies lay on the ground. The killing continued through the night, with soldiers carrying out mopping-up operations on a house-to-house basis in the apartment buildings adjacent to the square. Witnesses to the event claim that the bodies were later removed in garbage trucks.

The official government explanation of the incident was that armed provocateurs among the demonstrators, stationed in buildings overlooking the crowd, had begun the firefight. Suddenly finding themselves sniper targets, the security forces had simply returned fire in self-defense. In October 1997, the Mexican congress established a committee to investigate the Tlatelolco massacre. The committee interviewed many political players involved in the massacre, including Luis Echeverría Álvarez, a former president of Mexico who was Díaz Ordaz's minister of the interior at the time of the massacre. Echeverría admitted that the students had been unarmed, and suggested that the military action was planned, as a means to destroy the student movement.

In June 2006, an ailing, 84-year-old Echeverría was charged with genocide in connection with the massacre. He was placed under house arrest pending trial. In early July of that year, genocide charges were dropped, as the judge found that Echeverría could not be put on trial because of Mexico's statute of limitations.

CIA, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and State Department documents in this collection detail: That in response to Mexican government concerns over the security of the Olympic Games, the Pentagon sent military radios, weapons, ammunition and riot control training material to Mexico before and during the Mexico City demonstrations. The CIA station in Mexico City produced almost daily reports tracking developments within the university community and the Mexican government from July to October. Six days before the confrontation at Tlatelolco, both Echeverría and head of Federal Security (DFS) Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios told the CIA "the situation will be under complete control very shortly". That the Díaz Ordaz government "arranged" to have student leader Sócrates Campos Lemus accuse dissident PRI politicians, such as Carlos Madrazo, of funding and orchestrating the student movement.

1969 Operation Intercept

In the late 1960's U.S. officials believed that the drug problem in the United States had reached crisis proportions and they partially blamed Mexico as a major supplier. In 1969, the Nixon Administration did not believe Mexico was doing enough to prevent drugs crossing the United States/Mexico border. The Nixon administration launched a surprise, uni-lateral effort, Operation Intercept. In 1969, in an effort to drug stop trafficking across the Southwest Border, the Nixon Administration ordered that each person and vehicle crossing the border be inspected. The Nixon Administration hoped this would pressure Mexico into placing more resources into ant-drug efforts. However, Operation Intercept, as the project was called, tied up border traffic, angered the Mexican government, and disturbed the economy on both sides of the border. Operation Intercept essentially closed the Mexican border. As a result, Operation Intercept was soon terminated. Recognizing that interdiction alone was not a successful strategy, the United States Government subsequently increased aid to Mexico, and offered greater cooperation and technical assistance to eradicate cannabis and opium poppy plants.

1970 - 1974 Lucio Cabañas and the Party of the Poor

One of Mexico's most celebrated guerrilla leaders was a former rural schoolteacher named Lucio Cabañas Barrientos. Cabañas was born in El Porvenir, of Atoyac de Álvarez. He became politically active when he studied in Guerrero Normal and was a leader of the local student union. In 1962, he was elected to the post of General Secretary of the Federation of Socialistic Peasant Students of Mexico. When he began to work as a teacher, he also mediated in problems in other schools. When a rector of Juan Álvarez School in Atoyac demanded that all pupils wear a school uniform, Cabañas argued that some of the families were so poor they could hardly feed their children, not to mention buy them uniforms. The rector was fired, but his supporters remained. When a May 18, 1967 strike action ended in shooting and deaths, he fled to the mountains and joined the group of Genaro Vásques Rojas until Rojas' death on February 2, 1972.

When Cabañas came to the lead the Army of the Poor and Peasant's Brigade Against Injustice, they numbered perhaps 300 members and lived in the Guerrero Mountains. There are a number of legends about Cabañas, including that he had five women bodyguards and that he had a bag full of money to give to the poor. Leading the military arm of his Party of the Poor (Pdlp), Cabañas operated successfully for years in the rugged mountains of Mexico's Guerrero state. For many Mexicans, the Pdlp's Peasant Brigade of Justice ambushes of military and police units, kidnappings, bank robberies and other armed actions were an unwelcome specter of communist revolution, that by the late 1960s and early 1970s seemed to be gaining ground in Mexico as it had in other parts of Latin America. To others, however, Cabañas was a strong champion against an oppressive local regime and an indifferent central government whose policies had perpetuated the poverty, lack of opportunity and brutality that characterized day-to-day life in much of rural Mexico. Cabañas circulated a multipoint program that called for defeating the government of the rich and installing a new regime; expropriating factories and facilities for the workers' benefit; enacting broad financial, judicial, educational and social welfare reforms that focused on workers, peasants, Indians and women; and removing Mexico from the colonialism of the United States and other foreign countries.

The group financed itself through kidnappings and bank robberies. Three kidnappings in 1971, resulted in millions of pesos in ransom. Two of the kidnap victims were personal friends of Mexican President Echeverría. The Mexican military in 1971 denied that there were Mexican guerillas operating in Guerrero. Attributing the activity to ordinary bandits. The CIA believed the group might have been responsible for an April 1971 shoot-down of a helicopter belonging to Guerrero Governor Caritino Maldonado Pérez, resulting in the death of Perez. The Party of the Poor in 1973 kidnapped Francisco Sánchez López. When his family refuses to pay the ransom, he was murdered.

In 1974, the Mexican government increased the military presence in Guerrero. Documents show that the U.S. embassy reported in 1974, that the Mexican military in Guerrero engaged in illegal detentions and torture. According to one report Mexican forces, "murdered some prisoners after extracting all information they have to give."

In June 1974, Cabañas kidnapped Rubén Figueroa, the PRI governor of Guerrero. After Cabañas issued demands for the release of Figueroa. United States intelligence sources reported that the Mexican Government decided to hunt down Cabañas, even if it results in the death of Figueroa. After a few months, the Mexican military was not successful at tracking down Cabanas or rescuing Figueroa. In September, the Mexican government reported the liberation of Figueroa. Documents show that officials at the U.S. embassy doubted the official version the story. Suspicious was the fact it was reported that there were no military causalities. Later that month, Mexican newspapers reported that Figueroa admitted that a ransom was paid for his release.

When Cabañas and several key followers were finally hunted down and killed in Guerrero by the Mexican army in late 1974, it was cause for both official Mexican celebration as well as deep disappointment among some in Mexico's southern Sierra Madre, who saw Cabañas as a romantic revolutionary leader fighting for justice in rural Mexico. North of the border, however, Cabañas and his comrades' deaths earned only a short notice on the New York Times' back pages and limited commentary thereafter. The United States, focused on a host of Cold War security issues, had only passing interest in the death of an obscure Mexican insurgent whose group posed no serious military threat to the Mexican government.

Some human rights groups in Mexico have reported that approximately 650 civilians disappeared from Guerrero during these years. Approximately 400 of these were from Atoyac de Alvarez, Cabañas' home.

1971 Corpus Christi Massacre

Former head of Mexican internal security during the Tlatelolco Massacre, Luis Echeverría Alvarez, took office as president of Mexico in December of 1970. On May 1, 1971, student protestors at the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon in Monterrey shut down the campus. Students in Mexico City planned a march in support of students in Nuevo Leon. This protest to be held on June 10, would be the first major student demonstration in Mexico since the Tlatelolco Massacre.

The march began at the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), in the Casco de Santo Tomás. As about 10,000 students marched down Avenida San Cosme. Men in civilian clothing, carrying bamboo sticks and chains, met them. A melee proceeded that is believed to have ended with approximately 25 students dead. June 10, is the date of the Catholic Corpus Christi celebration. The event of June 10 would become known as the Corpus Christi Massacre.

The men who countered the demonstrators were known as the Halcones, Spanish for Falcons. Security forces of the federal distrtict trained these men. A report by State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) provides analysis on the massacre. The report refers to intelligence on how the government of Mexico organized and controlled the Halcones.

Some with connections to the Halcones received crowd control training in the United States. None of the men trained in the U.S. took part in the Corpus Christi Massacre. The trained men did not return to Mexico until July 1971. In January 1971, Mexico’s Foreign Relations Secretary Emilio Rabasa transmitted a request from President Echeverría, to U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Robert McBride. The request was for the U.S. to set up a program of police training for a group of Mexican security forces. According to a U.S. embassy telegram sent to the State Department, the focus of the training would be, "crowd control, dealing with student demonstrations, and riots. They would also be interested in training in physical defense tactics and hand-to-hand combat."

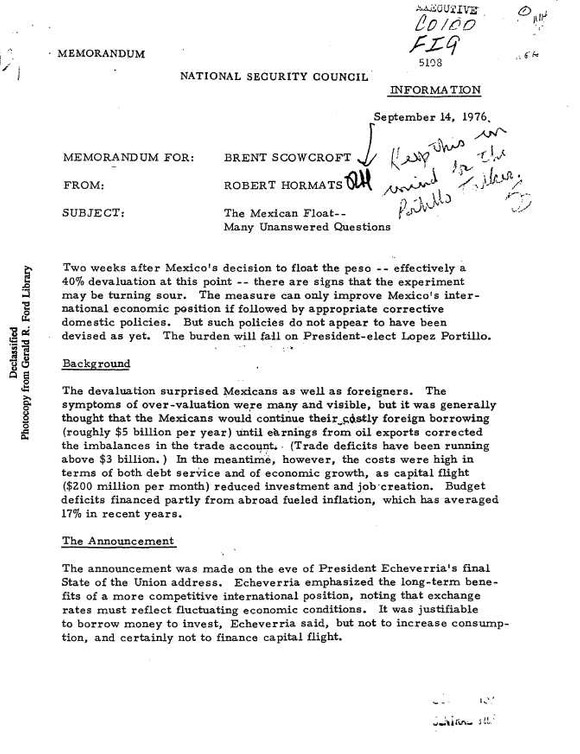

1976 - Economic Crisis

1992 - 1995 The Chiapas Rebellion

In 1992 and 1993, the Mexican government reported that military deployments in Chiapas were made to counter border-crossing Guatemalan guerrillas. United States intelligence documents from 1993 in this set identify the guerillas activities as being performed by a Mexican group, Zapatista National Liberation Front (FZLN).

Mexico's rural indigenous peoples periodically have risen in protest against poverty and encroachment by large farmers, ranchers, and commercial interests on contested land. A serious uprising occurred on January 1, 1994, when the Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional--EZLN) rebelled, capturing four municipalities in Chiapas state. The actions began on the eve of the inauguration of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Some of the group, believed to number about 1,600, were armed with semiautomatic and assault rifles, whereas others were armed only with sticks and wooden bayonets. Although the group's attacks seemed well planned, army units, supported by air force strikes, were able to regain control after the initial surprise. At least 12,000 troops were transported to the scene. Officials announced that 120 deaths had resulted, although church officials said 400 lives had been lost. Five rebels apparently were executed while bound and other deaths may have been the result of extrajudicial executions. Many disappearances of peasants were reported, and there was indiscriminate strafing of hamlets. The government declared a unilateral cease-fire after twelve days and announced several goodwill gestures as a prelude to reconciliation talks with the rebels, who were represented by their masked leader, Subcommander Marcos.

The EZLN, commonly known as the Zapatistas, is not a purely indigenous movement, but is instead an alliance of middle-class intellectuals and radicalized indigenous groups dating from the early 1980s. The EZLN began as an offshoot of the National Liberation Forces (Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional--FLN), a Maoist guerrilla group that had been largely dormant since the 1970s. At the start of the Zapatista rebellion, FLN veterans from Mexico City and a “clandestine committee” of Chiapas Indians representing the various ethnic groups residing in the area jointly held command of the Zapatista army.

In February 1995, on the eve of a new offensive against rebel strongholds, the government identified Subcommander Marcos as Rafael Sebastián Guillén, a white, middle-class graduate in graphics design from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México--UNAM). In the initial January 1994 Zapatista raids, the charismatic guerrilla leader had become an international media star, quickly assuming the status of a folk hero among many Mexicans. Capitalizing on his newfound fame and his proximity to the rebel army, Marcos is believed to have wrested control of the EZLN from its Mexico City leadership.

According to U.S. documents in this set, during the time of the Chiapas insurgency, the Mexican government received American weapons and military equipment, originally intended for the war on drugs. The Mexican government also received assistance from the militaries of Argentina, Britain, Chile, Guatemala, Israel, and Spain.

Despite a formidable government offensive involving approximately 20,000 army troops venturing into Zapatista-held territory, Subcommander Marcos and his rebel force eluded capture. By late February 1995, a second cease-fire had been declared. Soon thereafter, the government of Mexico and the rebels embarked on a second major round of peace talks. In early 1996, the Zapatistas declared their willingness in principle to lay down their arms and become a legal political party pending major reforms of the political system. Despite the ability to grab headlines and attract international support, the Zapatistas remained a marginal political force and were not considered a serious military threat outside of Chiapas.

1994 Financial Crisis

A devaluation of the peso in late 1994 threw Mexico into economic turmoil, triggering the worst recession in over half a century

About Collection Broad Coverage:

Highly developed cultures, including those of the Olmecs, Mayas, Toltecs, and Aztecs, existed long before the Spanish conquest. Hernando Cortes conquered Mexico during the period 1519-21 and founded a Spanish colony that lasted nearly 300 years. Father Miguel Hidalgo proclaimed Independence from Spain on September 16, 1810. Father Hidalgo’s declaration of national independence, known in Mexico as the "Grito de Dolores", launched a decade long struggle for independence from Spain. Prominent figures in Mexico’s war for independence were Father Jose Maria Morelos; Gen. Augustin de Iturbide, who defeated the Spaniards and ruled as Mexican emperor from 1822-23; and Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana, who went on to dominate Mexican politics from 1833 to 1855. An 1821 treaty recognized Mexican independence from Spain and called for a constitutional monarchy. The planned monarchy failed; a republic was proclaimed in December 1822 and established in 1824.

Throughout the rest of the 19th century, Mexico’s government and economy were shaped by contentious debates among liberals and conservatives, republicans and monarchists, federalists and those who favored centralized government. During the two presidential terms of Benito Juarez (1858-71), Mexico experimented with modern democratic and economic reforms. President Juarez’ terms of office, and Mexico’s early experience with democracy, were interrupted by the Habsburg monarchy’s rule of Mexico (1864-67), and was followed by the authoritarian government of Gen. Porfirio Diaz, who was president during most of the period between 1877 and 1911.

Mexico’s severe social and economic problems erupted in a revolution that lasted from 1910-20 and gave rise to the 1917 constitution. Prominent leaders in this period--some of whom were rivals for power--were Francisco Madero, Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, Alvaro Obregon, Victoriano Huerta, and Emiliano Zapata. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), formed in 1929 under a different name, emerged from the chaos of revolution as a vehicle for keeping political competition among a coalition of interests in peaceful channels.

In 1934, the Mexican constitution was changed to provide for the Sexenio. Sexenio is one of Mexico’s most important political institutions. It is the term limit on the Mexican Presidency, which limits the office holder to one six-year term. It is important because it is one of the few limitations on executive power in Mexico, which is strong at Local, State, and National levels. Without the Sexenio, Mexico would most likely not be considered a democracy since one party elects most presidents.

For 71 years, Mexico’s national government was controlled by the PRI, which won every presidential race and most gubernatorial races until the July 2000 presidential election of Vicente Fox Quesada of the National Action Party (PAN).

BROAD CONTEXT AREAS OF COVERAGE WITHIN THE FILES INCLUDE:

The Ruiz Cortines Sexenio, 1952-58

Despite his friendship with President Miguel Alemán Valdés, President Ruiz Cortines set out to eliminate the corruption and graft that had tainted the previous administration. In his inaugural speech on December 1, 1952, Ruiz Cortines promised to require complete honesty from officials in his government and asked that they make public their financial assets. He later fired several officials on charges of corruption.

The economy grew under Cortines, with government support. The government, for example, devaluated the peso, a move that encouraged investors from abroad. Ruiz Cortines did not promote a new construction boom, but rather channeled money into public health programs. The IMSS, under the directorship of Antonio Ortiz Mena, was expanded to provide medical services at hospitals and clinics throughout the country, and a more comprehensive system of benefits for eligible workers and their families was created.

By the end of Ruiz Cortines's sexenio in 1958, three consecutive presidential administrations had pursued pro-business policies that departed significantly from the agrarian populism practiced by former president Lázaro Cárdenas del Río. Import-substitution industrialization had generated rapid growth in urban areas, while land reform was scaled back and redefined to emphasize individual private farming. Meanwhile, Mexico's population more than doubled in less than thirty years, from 16 million in the mid-1930s to 34 million in 1960. The resulting population pressure, as well as the concentration of services and new jobs in urban areas, encouraged massive urban migration, most notably in and around Mexico City. The proliferation of urban shantytowns in the capital's outskirts became a growing symbol of the imbalance between urban and rural development in postwar Mexico.

With wartime calls for unity and austerity now well past, the Cárdenas faction of the PRI reemerged as a powerful force acting on behalf of the party's core agrarian and labor constituencies. Former President Cárdenas (who continued to wield considerable influence in national politics) persuaded the party to nominate one of his followers, Adolfo López Mateos, as the PRI candidate for the 1958 presidential election.

López Mateos and the Return to Revolutionary Policies, 1958-64

The election of López Mateos to the presidency in August 1958 restored to power the PRI faction that had historically emphasized nationalism and redistribution of land. As in past elections, the PRI won handily over the conservative candidate of the opposition National Action Party (Partido de Acción Nacional--PAN) with an overwhelming 90 percent of the vote. Although the PRI regularly engaged in vote buying and fraud at the state and local levels, presidential races were not credibly contested by the opposition, and little interference was required to keep the official party in office. Although the 1958 election was the first in which women were able to vote for the president, the enfranchisement of women did not significantly affect the outcome of the presidential race.

López Mateos was widely viewed as the political heir of Cárdenas, whose nationalism and social welfare programs had left a lasting impact on Mexican political culture. After nearly two decades of urban bias in government policy, López Mateos took tentative steps to redress the imbalance between urban and rural Mexico. His administration distributed more than 12 million hectares of land to ejidos and family farmers and made available new land for small-scale cultivation in southern Mexico. In addition, the IMSS program was introduced into rural areas, and major public health campaigns were launched to reduce tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, and malaria.

Whereas the government regained much of the support of agrarian interests, López Mateos's relations with organized labor were strained. As Ruiz Cortínes's labor minister, López Mateos had gained a reputation for fairness and competence in the settlement of labor disputes. As president however, he opposed the growing radicalization and militancy among elements of organized labor and acted forcefully to put down several major strikes. Reflecting a growing ideological polarization of national politics, the government imprisoned several prominent communists, including the famed muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Relations between labor and the government eased somewhat in 1962, when López Mateos revived a constitutional provision that called for labor to share in the profits of large firms.

Following Cárdenas's example, López Mateos restored a strongly nationalist tone to Mexican foreign policy, albeit not with the fervor that had characterized his populist predecessor. In 1960, the government began to buy foreign utility concessions (as opposed to expropriating them, as Cárdenas had done). Some of the larger companies bought were Electric Industries (Impulsora de Empresas Eléctricas) (from the American and Foreign Power Company of the United States), Mexican Light and Power Company (from a Belgian firm), and Mexican Electric Company (Industria Eléctrica Mexicana) (from the United States-based California Power Company). The film industry, previously owned by United States firms, was also brought under Mexican control. Mexican nationalism was most evident in its response to United States-led efforts to isolate the communist regime of Fidel Castro Ruz in Cuba. Alone among the members of the Organization of American States (OAS), Mexico refused to break diplomatic relations with Cuba or to observe the hemispheric embargo of the island approved at the OAS's Punta del Este Conference in 1962.

Authoritarianism Unveiled, 1964-70

By choosing his minister of interior, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, to succeed him, López Mateos yielded to growing concerns within the PRI about maintaining internal order and spurring economic growth. As government minister, Díaz Ordaz had been responsible for some very controversial policy decisions, including the arrest of Siqueiros, the violent suppression of several strikes, and the annulment of local elections in Baja California Sur, in which the PAN had received most of the votes.

Business interests once again received priority, and students and labor were kept under control so as not to disrupt economic growth. Anti-government protests reached unprecedented proportions, however, in the demonstrations of the summer of 1968, just prior to the Summer Olympic Games that were to be held in Mexico City in October. From July through October, academic life in the city and throughout Mexico was halted as students rioted. The anti-government demonstrations were ignited by student grievances, but many discontented sectors of society joined the students.

As the Olympic Games approached, the PRI and Díaz Ordaz were preparing the country to show foreign visitors that Mexico was politically stable and economically sound. Student unrest grew louder and more violent, however. Student demands included freedom for all political prisoners, dismissal of the police chief, disbanding of the anti-riot police, guarantees of university autonomy, and the repeal of the "law of social dissolution" (regulating the punishment of acts of subversion, treason, and disorder). Luis Echeverría Álvarez, the new interior minister, agreed to discuss the issues with the students but changed his mind when they demanded that the meeting be televised. The students, their demands unmet, escalated the scale and frequency of their protests. In late August, they convened the largest anti-government demonstration to date, rallying an estimated 500,000 protesters in the main plaza of the capital. Seeking to bring a halt to the demonstrations, Díaz Ordaz ordered the army to take control of UNAM and to arrest the student movement leaders.

To show that they had not been silenced, the students called for another rally at the Plaza of the Three Cultures in Mexico City's Tlatelolco district. On October 2, 1968, a crowd of about 5,000 convened on the plaza in defiance of the government crackdown. Armed military units and tanks arrived on the scene and surrounded the demonstrators, while military helicopters hovered menacingly overhead. The helicopters began to agitate the crowd by dropping flares into the densely packed gathering. Shortly thereafter, shots rang out (according to some accounts, the shooting was started by the military, while others claim the first shots were fired at soldiers by anti-government snipers in the surrounding buildings). The panicked crowd suddenly surged toward the military cordon, which reacted by shooting and bayoneting indiscriminately into the crowd. Estimates of the number of people killed ranged from several dozen to more than 400. Despite the violence, the Olympic Games proceeded on schedule. However, the Tlatelolco massacre had a profound and lasting negative effect on the PRI's public image. The authoritarian aspects of the political system had been starkly brought to the surface.

Reconciliation and Redistribution, 1970-76

Despite the groundswell of urban protest unleashed against the government, the PRI candidate easily won the 1970 presidential election. The new president, Echeverría, was expected to continue his predecessor's policies. Contrary to expectations, however, once in office Echeverría swung the ideological pendulum of the regime back to the left. The government embarked on an ambitious public relations campaign to regain the loyalty of leftist intellectuals and the young. To solidify the support of its core labor and agrarian constituencies, the PRI also launched a barrage of social welfare programs.

Echeverría was determined to co-opt the dissatisfied elements of the middle class that had become radicalized during the 1960s. Government patronage became an important mechanism of rapprochement. Thousands of intellectuals and young leftists were given posts in the government's bloated bureaucracy, and prominent student leaders were brought into the president's cabinet. To attract support from the young, who now represented a majority of Mexico's population, Echeverría lowered the voting age to eighteen, and the ages for election to the Senate and Chamber of Deputies to thirty and twenty-one, respectively. In addition, Echeverría freed most of the demonstrators arrested during the raid on UNAM and the Tlatelolco massacre.

Despite his aversion to domestic communist movements, Echeverría became a champion of leftist causes in Latin America. He was a strong advocate of the proposed "new international economic order" to redistribute power and wealth more equitably between the industrialized countries and the developing world. Demonstrating his independence from the United States, Echeverría became only the second Latin American head of state to visit Castro's Cuba. In 1974, he warmly received Hortensia Allende, widow of leftist Chilean president Salvador Allende Gossens, as a political refugee from Chile's right-wing military dictatorship.

In domestic economic affairs, the Echeverría administration ended the policies of stabilizing development that had been pursued since the early 1950s. Echeverría abandoned Mexico's commitment to growth with low inflation and undertook instead to stimulate the economy and redistribute wealth through massive public-spending programs. The new policy of "shared development" was premised on heavy state investment in the economy and the promotion of consumption and social welfare for the middle and lower classes.

The focus of Echeverría's social welfare policies was the Mexican countryside. Despite ample evidence that the ejidos were less efficient than private farming, Echeverría resumed the redistribution of land to ejidos and expanded credit subsidies to cooperative agriculture. The government also pursued an extensive program of rural development that increased the number of schools and health clinics in rural communities. By refusing to defend rural property owners from squatters, the Echeverría government encouraged a wave of land invasions that reduced land pressure in the countryside, but seriously undermined investor confidence.

In addition to providing broad subsidies for agriculture, the government embarked on several costly infrastructure projects, such as the US$1 billion Lázaro Cárdenas-Las Truchas Steel Plant (Sicartsa) steel complex in Michoacán state. State subsidies to stimulate private and parastatal investment grew from 16 billion pesos (US$1.2 billion) in 1970 to 428 billion pesos (US$18.6 billion) by 1980. Although this type of spending generated high economic growth throughout the 1970s, much of the money was either wasted in unnecessary and inefficient projects or lost to corruption. The government relied heavily on deficit spending to finance its domestic programs, incurring heavy debt obligations with foreign creditors to make up the shortfall in public revenues.

Under Echeverría, the historically uneasy relationship between the PRI and the national business community took a sharp turn for the worse. Echeverría's anti-business rhetoric and the government's interference in the economy deterred new foreign and domestic investment. Although the government avoided full-scale expropriations, it increased the state's role in the economy by buying out private shareholders and assuming control of hundreds of domestic enterprises. By the end of Echeverría's term, the government owned significant shares in more than 1,000 corporations nationwide.

Despite warning signs of a looming financial crisis, deficit spending continued unabated throughout Echeverría's sexenio. The public sector's foreign debt rose by 450 percent to US$19.6 billion in six years, while the peso was allowed to become overvalued. By the end of his sexenio, Echeverría was facing the consequences of his administration's unrestrained spending. In August 1976, mounting currency speculation, large-scale capital flight, and lack of confidence in Mexico's ability to meet its debt repayment schedule forced the government to devalue the peso for the first time since 1954. The outgoing president bequeathed to his successor, José López Portillo y Pacheco, an economy in recession and burdened by severe structural imbalances. The only bright spot in an otherwise bleak economic picture was the discovery in the mid-1970s of vast reserves of oil under the Bahía de Campeche and in the states of Chiapas and Tabasco

Recovery and Relapse, 1976-82

President López Portillo was inaugurated on December 1, 1976, amid a political and economic crisis inherited from the previous administration. A rising foreign debt and inflation rate, a 55 percent currency devaluation, and a general climate of economic uncertainty that had spurred capital flight plagued the Mexican economy. The new López Portillo administration also faced a general lack of confidence in government institutions. Unexpected help arrived because of the confirmation of the large oil reserves. The Mexican government chose to follow a policy of increasing oil production only gradually to prevent an inflationary spiral that would disrupt economic recovery. Nevertheless, by 1981 Mexico had become the fourth largest producer of oil in the world, its production having tripled between 1976 and 1982. While production increased, so did the price per barrel of crude oil.

The immense revenues generated by oil exports during the administration of López Portillo gave Mexico a greater degree of confidence in international affairs, particularly in its ever-important relations with the United States. The government, for example, refused to participate in the United States-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. When the two countries could not agree on the price of natural gas, Mexico flared its excess resources rather than sell to the United States below its asking price. Also in defiance of United States wishes, Mexico recognized the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front rebels in El Salvador as a representative political force. These steps occurred although the United States remained Mexico's major oil customer and its major source of investment capital.

As in so many developing countries, oil did not solve all of Mexico's problems, however. The oil industry grew rapidly but could not employ the ever-increasing ranks of the unskilled. Oil made Mexico a rich nation in which a majority of the people continued to live in poverty. Foreign banks and the international lending agencies, seeing Mexico as a secure investment with abundant energy resources, flooded the country with loans that kept the peso overvalued.

"The Crisis" Begins, 1982

Although its effects rippled through every aspect of national life, the roots of what came to be known simply as "the crisis" were exclusively economic. The roots of the crisis lay in the oil boom of the late 1970s. Oil prices rose sharply at a time when oil exploration in Mexico was at a peak. The nation found itself awash in petrodollars. Its infrastructure, barely adequate before the boom, was overwhelmed by the influx of imported goods that followed Mexico's rising foreign exchange reserves and the overvalued peso. López Portillo promised, "to transform nonrenewable resources into renewable wealth." In other words, he vowed to invest substantial amounts of the new oil revenue in areas and projects that would establish sustainable economic growth. This promise went unfulfilled.

Government spending did increase substantially following the oil boom. Little, if any, of the new spending, however, qualified as productive investment. Food subsidies, long a political necessity in Mexico, accounted for the largest single portion of the new spending. Although impossible to quantify, many accounts agree that the level of graft and corruption skyrocketed. The new money fueled a level of inflation never before seen in modern Mexico; the inflation rate eventually surpassed 100 percent annually. The López Portillo administration chose to ignore warning signs of inflation and opted instead to increase spending.

The macroeconomic trends that preceded the crisis also displayed warning signs that went unheeded. Oil income rose from 1979 to 1980. Oil exports began to crowd out other exports; the petroleum sector accounted for 45 percent of total exports in 1979, but dominated exports with 65.4 percent of the total in the second quarter of 1980. Like so many other developing nations, Mexico became a single-commodity exporter. With almost 50 billion barrels in proven reserves serving as collateral, Mexico also became a major international borrower. Significant foreign borrowing began under President Echeverría, but it soared under López Portillo. Foreign banks proved just as shortsighted as the Mexican government, approving large loans in the belief that oil revenue expansion would continue over the terms of the loans, assuring repayment. Hydrocarbon earnings for the period from 1977 to 1982, US$48 billion, were almost matched by public-sector external borrowing over the same period, which totaled US$40 billion. By 1982, almost 45 percent of export earnings went to service the country's external debt.

Living standards had already begun to decline when the oil glut hit in 1981. Although the economy grew by an average of 6 percent per year from 1977 to 1979, purchasing power over that period dropped by 6.5 percent. By mid-1981, overproduction had softened the international oil market considerably. In July, the government announced that it needed to borrow US$1.2 billion to compensate for lost oil revenue. The month before, Pemex had reduced its sales price for crude oil on the international market by US$4 per barrel. Continued high import levels and the drop in oil exports had boosted Mexico's current account deficit to US$10 billion. This uncertain situation, high external debt, stagnant exports, and a devalued currency as of February 1982, prompted investors to pull their money out of Mexico and seek safer havens abroad. This action, in turn, led López Portillo to nationalize the banks in September 1982 in an effort to staunch wounds that were largely of his own making.

López Portillo left office in 1982 a discredited figure, in no small part because the press publicized accounts of his luxurious lifestyle. The Mexican public, long-suffering and pragmatic in political matters, found López Portillo's calls for "sacrifice" and austerity unacceptable when contrasted with his own lifestyle.

To the Brink and Back, The de la Madrid Sexenio, 1982-88

When he took office in December 1982, Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado faced domestic conditions arguably more serious than those confronting any post-revolutionary president did. The foreign debt had reached new heights, the gross national product was contracting rather than growing, inflation had hit 100 percent annually, and the peso had lost 40 percent of its value. Moreover, and perhaps most critical, the Mexican people had begun to question and criticize the system of one-party rule that had caused this situation. Abroad, commentators (including United States president Ronald Reagan) speculated as to the potential for revolutionary upheaval in what had been considered a stable, if not democratic, southern neighbor. Some Mexicans shared this concern. The government and most in the PRI, de la Madrid included, believed that they could continue to hold power by keeping the people well fed and reversing economic trends.

Handpicked by López Portillo, de la Madrid inherited the former president's economic mismanagement and that of several of his predecessors. Lack of fiscal restraint, encouraged by a sudden flood of oil wealth, lay at the root of the crisis. Overprinting of the peso cheapened the currency, fed inflation, and exacerbated rather than cured the economic sins that prompted it. In addition, corruption, the traditional parasite of economic vitality in Mexico, made its contribution to the crash.

Although weak compared with earlier presidents, de la Madrid still wielded formidable power in both the economic and political arenas. The day of his inauguration, he recognized the nation's "emergency situation" by instituting a sweeping program of economic austerity measures. The ten-point program included federal budget cuts, new taxes, price increases on some previously subsidized items, postponement of many scheduled public works projects, increases in some interest rates, and the relaxation of foreign-exchange controls enacted during the waning days of the López Portillo administration. Aside from its anticipated adverse impact on the standard of living, many Mexicans resented the program for other reasons. Nationalists saw the measures as inspired and all but imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which reportedly had taken a hard line in debt talks with the government. Others resented the austerity edicts, because they believed that the government and the PRI had brought the nation to the brink of ruin, but that the people would have to bear the burden of official incompetence.

The sudden reversal of a long trend of steady economic growth in Mexico threw the political system into turmoil, undermined the authority of the PRI, and raised the already high levels of popular skepticism. Economic austerity exacerbated the elitist aspect of the populist authoritarian system that developed after the Revolution. Conditions such as inflation, devaluation, and the withdrawal of subsidies hit the poor hardest. The wealthy found ways to insulate themselves from such developments; as a result, the rich grew richer. This was true both within the private sector and among the bureaucracy. In addition to the schism between the poor and the rich in Mexico, the crisis and its impact on the PRI's authority sharpened the longstanding dichotomy between central and southern Mexico and the north. The immediate political beneficiary of the crisis was the PAN, a conservative, pro-business party with its roots in the northern border states.

To counteract the ferment, the government decided to allow some opening of the political system, enough to provide a safety valve for public discontent, but not enough to threaten the PRI's control, a balance difficult to attain. The first volley in the campaign against the PRI and its policies came with the elections of July 3, 1983. Although the PRI took a large majority of municipal and state legislative races in five northern states, the PAN captured an unprecedented nine mayoralties and registered gains in all five state legislatures.

In addition to the economic and political arenas, de la Madrid sought to exert influence in the area of ethics. Early in his administration, the president announced a program of "moral renewal." Despite its high-minded rhetoric, the program never enacted major legislation to discourage corrupt practices. One exception was a new rule that eliminated government subcontracting, a device that union leaders often used to earn kickbacks from contractors. In addition to instituting this new rule, the moral renewal campaign chose to make examples of a handful of corrupt officials, including former Pemex director Jorge Díaz Serrano and former Mexico City police chief Arturo Durazo Moreno, both of whom served prison sentences for illegal personal gain.

The United States and the Crisis in Mexico

Historically, United States relations with Mexico have followed a reactive pattern of neglect, activism, and intervention. The crisis of the 1980s, which appeared to threaten the longstanding stability of Mexico, triggered a new period of activist attention to its southern neighbor by the United States. The prospect of an economically overextended Mexico defaulting on US$100 billion in foreign loans caused alarm in Washington and throughout the industrialized world. The possibility of resulting political upheaval was particularly worrying to the United States. As a result, other issues between the two countries, migration, drugs, environmental concerns, investment, and trade, received increased attention.

United States president Ronald Reagan, a former governor of California, brought to the White House an appreciation of the importance of the relationship between the two countries. Reagan met with President López Portillo in Ciudad Juárez on January 5, 1981, becoming the first United States president-elect to visit Mexico. One of the topics that the two leaders discussed in Ciudad Juárez was the political crisis in Central America, where the leftist Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional--FSLN), also known as Sandinistas, held power in Nicaragua and supported guerrilla movements in El Salvador and Guatemala. López Portillo reportedly cautioned Reagan, a conservative who had strongly condemned the Nicaraguan government, regarding United States intervention in the region. At this time, Mexico considered Central America, particularly Guatemala, to lie within its geopolitical sphere of influence. Mexican policy, since the victory of the FSLN in 1979, had sought to provide an alternative to United States, Cuban, or Soviet influence on the isthmus. This Mexican strategy, however, eventually failed because Cuban influence on the Nicaraguan Sandinistas was rooted in years of clandestine support for the revolutionary cause.

The United States, however, rejected Mexico's conciliatory approach to Central American affairs in favor of military support to friendly governments, such as those in El Salvador and Honduras, and the even more controversial policy of backing anti-Sandinista guerrilla forces. After the economic crisis of 1982, Mexico lost much of its influence in Central America. Mexican governments, in turn, also became more guarded in their criticism of United States policy in order to assure Washington's support in financial forums such as the World Bank and the IMF.

Although the two nations did not always agree on the best strategy for dealing with Mexico's burgeoning foreign debt, the United States government continued to work with the Mexicans and support efforts to buoy the Mexican economy and reschedule the debt. Washington announced the first of several debt relief agreements in August 1982. Under the terms of the agreement, the United States purchased ahead of schedule some US$600 million in Mexican crude oil for its strategic oil reserve; the United States treasury also provided US$1 billion in guarantees for new commercial bank loans to Mexico. Privately, United States officials reportedly pressured commercial banks to postpone a US$10 billion principal payment that fell due that same month.

A bank advisory group representing 530 foreign creditors reached an accord with Mexico in late August 1984. The rescheduling agreement allowed Mexico to repay its foreign debt over a term of fourteen years at interest rates lower than those originally contracted. United States Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul A. Volcker, among others, had pushed for the interest rate reduction, in part as recognition of Mexico's having instituted difficult austerity measures and needing some fiscal relief in order to restore economic growth.

Other concerns meanwhile strained the Mexican-United States relationship. Perhaps the most dramatic was drug trafficking. The consumption of cocaine rose steadily in the United States during the late 1970s and early 1980s, becoming a major law enforcement and public health problem. Mexico has never been a major producer of cocaine. Geography, however, made Mexico a conduit for the transshipment of cocaine hydrochloride from South America to the United States. Difficult terrain; sparse population in many rural areas; an adequate infrastructure for transporting goods by land, sea, and air; and the relative ease of bribing both local and federal officials all lured drug traffickers to use Mexico as a conduit.

Eventually, an isolated incident came to symbolize Mexican drug corruption and the friction between the two nations on the issue of drug trafficking. The United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) maintained a comparatively large presence in Mexico. One of its resident offices operated out of the consulate in Guadalajara. In March 1985, Mexican authorities unearthed the body of DEA special agent Enrique Camarena on a ranch in Michoacán state, some 100 kilometers from Guadalajara. Mexican drug traffickers, reports later revealed, had tortured Camarena to death, perhaps in retaliation for his discovery of a major marijuana cultivation operation. Initial protest from the United States government brought little or no response from Mexican officials. As a result, the United States Customs Service closed nine lesser points of entry from Mexico to the United States and began searching every vehicle that passed northward. The resultant traffic backups, complaints, and economic losses infuriated the Mexican government. Mexicans claimed that the appearance of their inaction stemmed from misperceptions of the Mexican legal system, not from efforts to protect drug traffickers.

Despite the eventual arrest of a key suspect in the Camarena murder, relations between the United States and Mexico on the drug issue followed a rocky course. On April 14 and 15, 1985, United States Attorney General Edwin Meese III met with his Mexican counterpart, Sergio García Ramírez. The two agreed to closer monitoring of the two nations' joint counterdrug programs. The Camarena case, however, continued to cast a pall over these efforts. Leaked information from the United States Department of State and from law enforcement agencies indicated that Mexican authorities had made only token efforts against drug production and trafficking. According to Department of State figures, by the end of 1985, Mexico was the largest exporter of marijuana and heroin to the United States. Efforts at eradicating these crops had failed abysmally, and output in 1985 exceeded 1984 levels.

As controversy continued over Mexican drug policy, United States politics forced another bilateral issue to the fore. The United States had made sporadic efforts over the years to exert greater control over its porous southern border. Mexican and Central American illegal immigrants crossed the border almost at will to seek low-paid jobs. Organized labor, among others, urged the United States Congress to act. This pressure, based on the belief that illegal aliens took large numbers of jobs that United States citizens might otherwise fill, gave impetus to the Simpson-Rodino bill of 1986. The bill's two major provisions constituted a carrot and a stick for illegal immigrants. The carrot came in the form of an amnesty for all undocumented residents who could prove continuous residence in the United States since January 1, 1982. The stick imposed legal sanctions on employers of illegal aliens, an unprecedented attempt to deter migrants indirectly by denying them employment.

The Simpson-Rodino bill, which became law as the United States Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, represented the most serious effort to date to reduce illegal Mexican immigration. Northern migration had provided an economic safety valve from the Mexican economy's chronic inability to produce sufficient employment. Many Mexicans resented the timing of this new law, which came in the midst of severe economic distress in Mexico and relative prosperity in the United States. Although the level of migration dropped immediately after passage of the law, joblessness and poverty eventually drove the number of illegal migrants up again.

Despite the irritants of drug trafficking and migration, the United States concern for stability in Mexico led both countries to continue the search for a solution to Mexico's crushing debt burden. By the end of 1987, the United States government publicly recognized that Mexico could not "grow its way out" of the debt merely by stretching out payments and investing more borrowed funds. Acknowledging that some portion of the debt would never be repaid, the Department of the Treasury offered to issue zero-coupon bonds that would allow Mexico to buy back its debt at a discount. Although not a panacea, the plan represented a new approach to the debt problem, one that helped to improve Mexican public opinion of the United States.

Economic Hardship