Starting from:

$12.95

Home

Women's Studies

Susan B. Anthony Suffrage/Women's Rights Newspaper: The Revolution (1868-1872) - Download

Susan B. Anthony Suffrage/Women's Rights Newspaper: The Revolution (1868-1872) - Download

Susan B. Anthony Suffrage/Women's Rights Newspaper: The Revolution

3,408 pages of The Revolution, the women's rights weekly newspaper created by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, ranging from its first issue January 8, 1868 to its last February 17, 1872.

The Revolution has been described as, "one of the most important documentary sources for the history of women in the nineteenth century," by Cheris Kramarae and Lana F. Rakow, authors of "The Revolution in Words, Righting Women, 1868-1871." Modern day readers of The Revolution are allowed an opportunity to receive the concerns, complaints, solutions, principles, and philosophies that existed in the minds of many women of its era, communicated directly from them.

Founded by women's rights activists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York City, its first issue was published on January 8, 1868. Anthony handled the business side of the weekly, while Stanton along with co-editor Parker Pillsbury, a leading male feminist of his day, were responsible for its content. The start-up funding for the newspaper was provided for by the controversial and eccentric businessman George Francis Train. This troubled many in suffrage movement who had ties to the Republican Party. During the Civil War Democrat Train gave speeches that were anti-succession, but pro-slavery, which lead to him being called a "copperhead," an epithet for northern Democrat supporters of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In 1851, Anthony and Stanton were introduced to each other and soon formed a lifelong friendship and collaboration on social reform activities. In 1852, they founded the New York Women's State Temperance Society, due to Anthony being refused the opportunity to speak at a temperance conference because she was a woman. In 1863, they founded the Women's Loyal National League, which conducted the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, collecting nearly 400,000 signatures in support of the abolition of slavery. In 1866, they initiated the American Equal Rights Association, which according to its constitution, was created "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." In 1868, they began publishing The Revolution. When disagreements over doctrine and tactics split the women's movement, in 1869 they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Before "The Revolution" the two most prominent women's rights newspapers were "The Lily" created in by Amelia Jenks Bloomer, published from 1849 to 1851 and "The Una: A Paper Devoted to the Elevation of Woman," created by Paulina Wright Davis and published from 1853 to 1855. Lucy Stone began publication of a rival paper, "The Woman’s Journal," in January of 1870. Among these journals The Revolution was considered to be the most radical for its time.

The first issue, January 8, 1868, carried beneath its title on the front page its first slogan, “Principle, not Policy: Justice, Not Favor." By its second issue the paper added to the end of its motto, "Men their Rights and Nothing More, Women their Rights and Nothing Less." The paper directly advocated for the recognition of essential rights and liberties denied to women, through a combative style true to its name. It covered not only suffrage for women but also social issues, politics, labor movements and finance. The paper touched subjects that were taboo in other newspapers such as domestic violence, divorce, rape, prostitution, and reproductive rights.

In its mission statement the Revolution declared that it would advocate, "IN POLITICS-Educated Suffrage, Irrespective of Sex or Color; Equal Pay to Women for Equal Work; Eight Hours Labor; Abolition of-Standing Armies and Party Despotisms. Down with Politicians-Up with the People!"

The paper carried: Coverage of news and events pertinent to the scope of the newspaper; Imparting of the activities and opinions of the paper's founders, editors, and authors; letters and contributions from readers and others in the women's movement; Stories on the founding and proceedings of the National Woman Suffrage Association; A financial section covering monetary and trade policies; Foreign correspondence, reporting from women outside the United States on the status and progress of women in other parts of the world; Poetry and fiction; Announcements of events; Transcripts of speeches, conference proceedings, and testimony before government bodies.

One of the successes of the paper was that it put women's rights and suffrage back in the mainstream after attention to these issues diminished during the years America's attention was focused on the Civil War. The paper established the leadership roles of Anthony and Stanton in the suffrage movement of the second half of the 19th century. The activity surrounding the creation and publishing of the Revolution lead to the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In 1890 the NWSA merged with American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The Revolution was able to attract more working-class women to the women’s movement by covering unionization and discrimination against female workers.

In 1868, the paper ran a campaign in support of Hester Vaughn. Vaughn was a domestic worker who had a child fathered by her former employee. When the child died soon after birth she was accused and convicted of allowing the baby to die. Describing the condemned to death Vaughn as a "poor, ignorant, friendless and forlorn girl who had killed her newborn child because she knew not what else to do with it", an editorial in The Revolution said, "If that poor child of sorrow is hung, it will be deliberate, downright murder. Her death will be a far more horrible infanticide than was the killing of her child."

As the Vaughn campaign continued, The Revolution reported a different set of facts, implying that the baby's death had occurred either naturally or accidentally: "During one of the fiercest storms of last winter she was without food or fire or comfortable apparel. She had been ill and partially unconscious for three days before her confinement, and a child was born to Hester Vaughn. Hours passed before she could drag herself to the door and cry out for assistance, and when she did it was to be dragged to a prison." After publicizing the case, Stanton visited

Pennsylvania governor John W. Geary who pardoned Vaughn. Soon after she was deported back to England.

Many social reformers were deeply dismayed at The Revolution's refusal to support the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise black men, unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would also enfranchise women. By the time the Fifteenth Amendment was making its way through Congress, Stanton's position had led to a major schism in the women's rights movement itself. Many leaders in the women's rights movement, including Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe, strongly argued against Stanton's "all or nothing" position. Stanton, who came from a socially prominent and wealthy family, opposed it in The Revolution with language that was sometimes elitist and racially condescending. Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

By 1869, disagreement over ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment had given birth to two separate women's suffrage organizations. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was founded by Anthony and Stanton. The NWSA opposed passage of the Fifteenth Amendment without changes to include female suffrage and, under Stanton's influence in particular, championed a number of women's issues that were deemed too radical by more conservative members of the suffrage movement. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was passed with its original language, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

By this time the newspaper began to hit major financial bumps. George Francis Train, provided $3,000 and his business partner George Francis Train $7,000 toward the creation of the newspaper. However, Train as a source of funding ended soon after the first issue the paper was published. In early 1868, Train went to England where he was arrested and jailed for supporting Irish independence. Anthony resisted raising the price of a subscription to the paper and refused to allow lucrative adverting for questionable medical products which were often laden with alcohol and morphine.

By May 1870, The Revolution was deeply in debt. Anthony assumed $10,000 of debt and sold the paper for $1 to wealthy women's rights activist Laura Curtis Bullard. Much of Anthony's earnings from the lecture circuit over the next six years went to paying off the debt.

Bullard gave the paper a more conservative tone and addressed women's issues in a less radical fashion. Bullard gave The Revolution a new motto, "What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder." Stanton and some others who had previously been published in the Revolution occasionally contributed to the paper while under the management of Bulllard.

Bullard attempted to increase revenue by selling more advertisements, including those for patent medicines, which Anthony refused to publish, many of them produced by Bullard's family business. In October 1871 Bullard resigned from the newspaper.

On October 28, 1871, control of newspaper was transferred to Reverend. W. T. Clarke, and publisher, J. N. Hallock. They gave the newspaper a new motto, “Devoted to the Interest of Woman and Home Culture". Clarke was for women's suffrage; however he took a different approach than previous editors of the Revolution. In his first issue Clarke wrote, "Most men are exceedingly kind to women, and treat them with too much tenderness rather than too little. More women among us are injured by indulgence rather than injustice."

Four months later The Revolution published its last issue on February 17, 1872. Forty-eight years later, the Nineteenth Amendment to the constitution was ratified stating, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

Front page of the first issue of The Revolution January 8, 1868

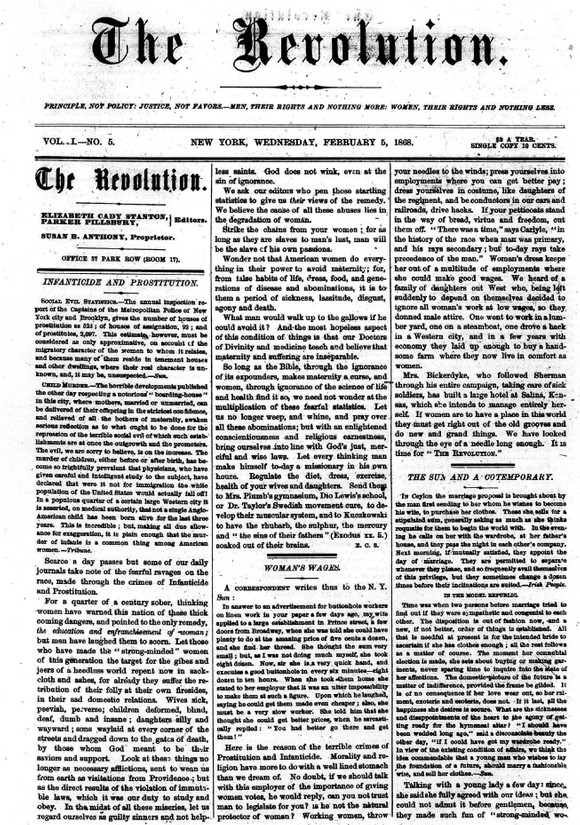

The Revolution February 5, 1868

Highlights include:

The Revolution July 9, 1868, Pages 8 and 9

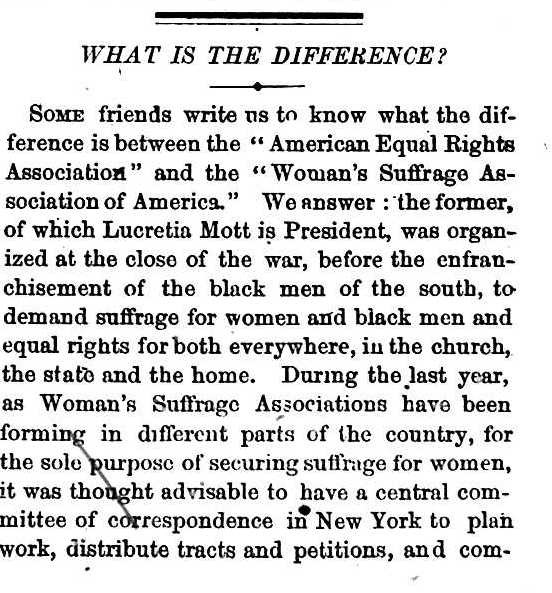

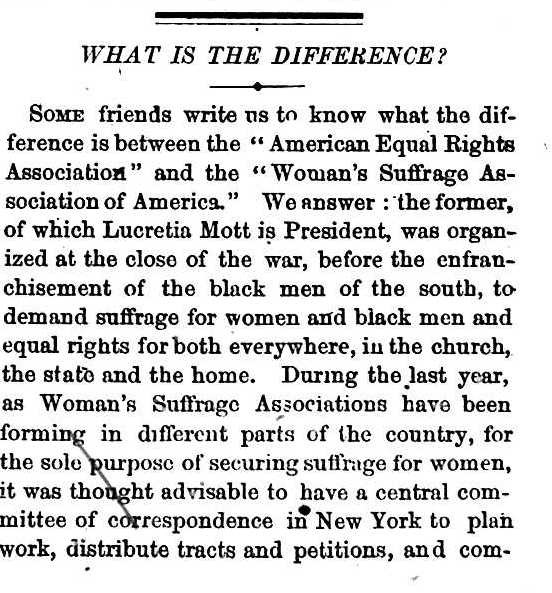

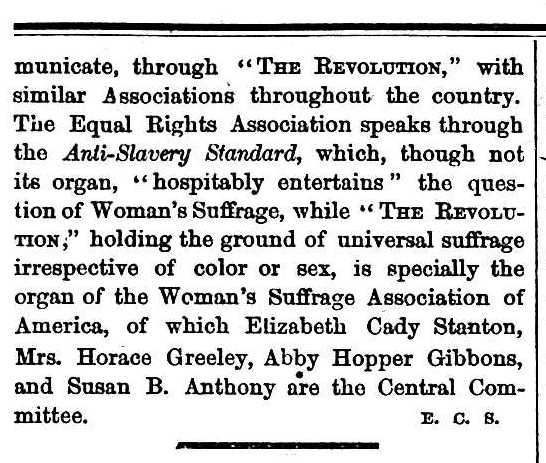

In May 1868, The Revolution announced the formation of the Woman's Suffrage Association of America to serve as a coordinating committee for the local women's suffrage organizations that had developed around the country. Its officers included Stanton and Anthony, and it shared The Revolution's office. Stanton later said, "The Revolution, holding the ground of universal suffrage irrespective of color or sex, is specially the organ of the Woman's Suffrage Association of America."

The Revolution, October 1, 1868, page 200

The Revolution supported the success of the National Labor Union (NLU), Anthony and Stanton hoped to join forces with it to create a broad alliance, leading to the formation of a new political party, one that would support women's suffrage as well as the demands of working people. The Revolution declared, "The principles of the National Labor Union are our principles." It predicted that, "The producers, the working-men, the women, the negroes, are destined to form a triple power that shall speedily wrest the scepter of government from the non-producers and the land monopolists, the bond-holders, the politicians." Although the NLU responded warmly to The Revolution's overtures, the anticipated alliance did not develop.

The Revolution, November 5, 1868

In the aftermath of the Civil War, major periodicals associated with the radical social reform movements had either become more conservative or had quit publishing or soon would. Anthony intended for The Revolution to partially fill that void, hoping to grow it eventually into a daily paper with its own printing press, all owned and operated by women.

The Revolution, November 19, 1868, page 305

The Woman's Suffrage Association of America published a petition in The Revolution in favor of women's suffrage and asked its readers to circulate it.

The Revolution, April 29, 1869, page 266

Many social reformers were deeply dismayed at The Revolution's refusal to support the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise black men, unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would also enfranchise women. Stanton, who came from a wealthy and socially prominent family, opposed it in The Revolution with language that was sometimes elitist and racially condescending. Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

The Revolution, August 12, 1869, page 88

The paper sparred vigorously with its opponents. When the New York World criticized the women's movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, responded, "The World innocently asks us the question, why, like the Englishwomen, we do not sit still in our conventions, and get ‘first class men’ to do the speaking? We might, with equal propriety, ask the World's editorial staff why they do not lay down their pens and get first class men to edit their journal?”

The Revolution, September 15, 1870

Bullard gave the paper a new motto, the Biblical phrase: "What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder", which was often quoted in marriage ceremonies. One historian has conjectured that Bullard selected the motto partly to fend off accusations that the women's rights movement would destroy the institution of marriage. She gave it her own interpretation, however, saying "it is a time-honored form of words expressing not only one limited idea but many other noble meanings." Woman, she continued, "has been systematically divorced from [man] from the beginning of time: she is now to proclaim and enforce her marriage rights. She is to have an equal place with him in the trades, in the colleges, in the lyceum, in the press, in literature, in science, in art, in government, in everything.”

3,408 pages of The Revolution, the women's rights weekly newspaper created by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, ranging from its first issue January 8, 1868 to its last February 17, 1872.

The Revolution has been described as, "one of the most important documentary sources for the history of women in the nineteenth century," by Cheris Kramarae and Lana F. Rakow, authors of "The Revolution in Words, Righting Women, 1868-1871." Modern day readers of The Revolution are allowed an opportunity to receive the concerns, complaints, solutions, principles, and philosophies that existed in the minds of many women of its era, communicated directly from them.

Founded by women's rights activists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York City, its first issue was published on January 8, 1868. Anthony handled the business side of the weekly, while Stanton along with co-editor Parker Pillsbury, a leading male feminist of his day, were responsible for its content. The start-up funding for the newspaper was provided for by the controversial and eccentric businessman George Francis Train. This troubled many in suffrage movement who had ties to the Republican Party. During the Civil War Democrat Train gave speeches that were anti-succession, but pro-slavery, which lead to him being called a "copperhead," an epithet for northern Democrat supporters of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In 1851, Anthony and Stanton were introduced to each other and soon formed a lifelong friendship and collaboration on social reform activities. In 1852, they founded the New York Women's State Temperance Society, due to Anthony being refused the opportunity to speak at a temperance conference because she was a woman. In 1863, they founded the Women's Loyal National League, which conducted the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, collecting nearly 400,000 signatures in support of the abolition of slavery. In 1866, they initiated the American Equal Rights Association, which according to its constitution, was created "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." In 1868, they began publishing The Revolution. When disagreements over doctrine and tactics split the women's movement, in 1869 they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Before "The Revolution" the two most prominent women's rights newspapers were "The Lily" created in by Amelia Jenks Bloomer, published from 1849 to 1851 and "The Una: A Paper Devoted to the Elevation of Woman," created by Paulina Wright Davis and published from 1853 to 1855. Lucy Stone began publication of a rival paper, "The Woman’s Journal," in January of 1870. Among these journals The Revolution was considered to be the most radical for its time.

The first issue, January 8, 1868, carried beneath its title on the front page its first slogan, “Principle, not Policy: Justice, Not Favor." By its second issue the paper added to the end of its motto, "Men their Rights and Nothing More, Women their Rights and Nothing Less." The paper directly advocated for the recognition of essential rights and liberties denied to women, through a combative style true to its name. It covered not only suffrage for women but also social issues, politics, labor movements and finance. The paper touched subjects that were taboo in other newspapers such as domestic violence, divorce, rape, prostitution, and reproductive rights.

In its mission statement the Revolution declared that it would advocate, "IN POLITICS-Educated Suffrage, Irrespective of Sex or Color; Equal Pay to Women for Equal Work; Eight Hours Labor; Abolition of-Standing Armies and Party Despotisms. Down with Politicians-Up with the People!"

The paper carried: Coverage of news and events pertinent to the scope of the newspaper; Imparting of the activities and opinions of the paper's founders, editors, and authors; letters and contributions from readers and others in the women's movement; Stories on the founding and proceedings of the National Woman Suffrage Association; A financial section covering monetary and trade policies; Foreign correspondence, reporting from women outside the United States on the status and progress of women in other parts of the world; Poetry and fiction; Announcements of events; Transcripts of speeches, conference proceedings, and testimony before government bodies.

One of the successes of the paper was that it put women's rights and suffrage back in the mainstream after attention to these issues diminished during the years America's attention was focused on the Civil War. The paper established the leadership roles of Anthony and Stanton in the suffrage movement of the second half of the 19th century. The activity surrounding the creation and publishing of the Revolution lead to the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In 1890 the NWSA merged with American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The Revolution was able to attract more working-class women to the women’s movement by covering unionization and discrimination against female workers.

In 1868, the paper ran a campaign in support of Hester Vaughn. Vaughn was a domestic worker who had a child fathered by her former employee. When the child died soon after birth she was accused and convicted of allowing the baby to die. Describing the condemned to death Vaughn as a "poor, ignorant, friendless and forlorn girl who had killed her newborn child because she knew not what else to do with it", an editorial in The Revolution said, "If that poor child of sorrow is hung, it will be deliberate, downright murder. Her death will be a far more horrible infanticide than was the killing of her child."

As the Vaughn campaign continued, The Revolution reported a different set of facts, implying that the baby's death had occurred either naturally or accidentally: "During one of the fiercest storms of last winter she was without food or fire or comfortable apparel. She had been ill and partially unconscious for three days before her confinement, and a child was born to Hester Vaughn. Hours passed before she could drag herself to the door and cry out for assistance, and when she did it was to be dragged to a prison." After publicizing the case, Stanton visited

Pennsylvania governor John W. Geary who pardoned Vaughn. Soon after she was deported back to England.

Many social reformers were deeply dismayed at The Revolution's refusal to support the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise black men, unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would also enfranchise women. By the time the Fifteenth Amendment was making its way through Congress, Stanton's position had led to a major schism in the women's rights movement itself. Many leaders in the women's rights movement, including Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe, strongly argued against Stanton's "all or nothing" position. Stanton, who came from a socially prominent and wealthy family, opposed it in The Revolution with language that was sometimes elitist and racially condescending. Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

By 1869, disagreement over ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment had given birth to two separate women's suffrage organizations. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was founded by Anthony and Stanton. The NWSA opposed passage of the Fifteenth Amendment without changes to include female suffrage and, under Stanton's influence in particular, championed a number of women's issues that were deemed too radical by more conservative members of the suffrage movement. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was passed with its original language, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

By this time the newspaper began to hit major financial bumps. George Francis Train, provided $3,000 and his business partner George Francis Train $7,000 toward the creation of the newspaper. However, Train as a source of funding ended soon after the first issue the paper was published. In early 1868, Train went to England where he was arrested and jailed for supporting Irish independence. Anthony resisted raising the price of a subscription to the paper and refused to allow lucrative adverting for questionable medical products which were often laden with alcohol and morphine.

By May 1870, The Revolution was deeply in debt. Anthony assumed $10,000 of debt and sold the paper for $1 to wealthy women's rights activist Laura Curtis Bullard. Much of Anthony's earnings from the lecture circuit over the next six years went to paying off the debt.

Bullard gave the paper a more conservative tone and addressed women's issues in a less radical fashion. Bullard gave The Revolution a new motto, "What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder." Stanton and some others who had previously been published in the Revolution occasionally contributed to the paper while under the management of Bulllard.

Bullard attempted to increase revenue by selling more advertisements, including those for patent medicines, which Anthony refused to publish, many of them produced by Bullard's family business. In October 1871 Bullard resigned from the newspaper.

On October 28, 1871, control of newspaper was transferred to Reverend. W. T. Clarke, and publisher, J. N. Hallock. They gave the newspaper a new motto, “Devoted to the Interest of Woman and Home Culture". Clarke was for women's suffrage; however he took a different approach than previous editors of the Revolution. In his first issue Clarke wrote, "Most men are exceedingly kind to women, and treat them with too much tenderness rather than too little. More women among us are injured by indulgence rather than injustice."

Four months later The Revolution published its last issue on February 17, 1872. Forty-eight years later, the Nineteenth Amendment to the constitution was ratified stating, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

Front page of the first issue of The Revolution January 8, 1868

The Revolution February 5, 1868

Highlights include:

The Revolution July 9, 1868, Pages 8 and 9

In May 1868, The Revolution announced the formation of the Woman's Suffrage Association of America to serve as a coordinating committee for the local women's suffrage organizations that had developed around the country. Its officers included Stanton and Anthony, and it shared The Revolution's office. Stanton later said, "The Revolution, holding the ground of universal suffrage irrespective of color or sex, is specially the organ of the Woman's Suffrage Association of America."

The Revolution, October 1, 1868, page 200

The Revolution supported the success of the National Labor Union (NLU), Anthony and Stanton hoped to join forces with it to create a broad alliance, leading to the formation of a new political party, one that would support women's suffrage as well as the demands of working people. The Revolution declared, "The principles of the National Labor Union are our principles." It predicted that, "The producers, the working-men, the women, the negroes, are destined to form a triple power that shall speedily wrest the scepter of government from the non-producers and the land monopolists, the bond-holders, the politicians." Although the NLU responded warmly to The Revolution's overtures, the anticipated alliance did not develop.

The Revolution, November 5, 1868

In the aftermath of the Civil War, major periodicals associated with the radical social reform movements had either become more conservative or had quit publishing or soon would. Anthony intended for The Revolution to partially fill that void, hoping to grow it eventually into a daily paper with its own printing press, all owned and operated by women.

The Revolution, November 19, 1868, page 305

The Woman's Suffrage Association of America published a petition in The Revolution in favor of women's suffrage and asked its readers to circulate it.

The Revolution, April 29, 1869, page 266

Many social reformers were deeply dismayed at The Revolution's refusal to support the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise black men, unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would also enfranchise women. Stanton, who came from a wealthy and socially prominent family, opposed it in The Revolution with language that was sometimes elitist and racially condescending. Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

The Revolution, August 12, 1869, page 88

The paper sparred vigorously with its opponents. When the New York World criticized the women's movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, responded, "The World innocently asks us the question, why, like the Englishwomen, we do not sit still in our conventions, and get ‘first class men’ to do the speaking? We might, with equal propriety, ask the World's editorial staff why they do not lay down their pens and get first class men to edit their journal?”

The Revolution, September 15, 1870

Bullard gave the paper a new motto, the Biblical phrase: "What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder", which was often quoted in marriage ceremonies. One historian has conjectured that Bullard selected the motto partly to fend off accusations that the women's rights movement would destroy the institution of marriage. She gave it her own interpretation, however, saying "it is a time-honored form of words expressing not only one limited idea but many other noble meanings." Woman, she continued, "has been systematically divorced from [man] from the beginning of time: she is now to proclaim and enforce her marriage rights. She is to have an equal place with him in the trades, in the colleges, in the lyceum, in the press, in literature, in science, in art, in government, in everything.”

2 files (1.8GB)