Starting from:

$12.95

Home

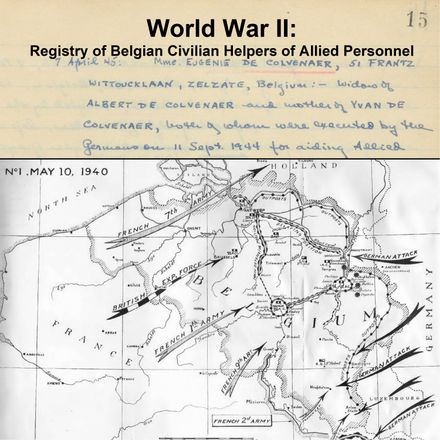

World War II

World War II: Malmedy Massacre - Murder of American POWs Investigation & Trial Documents

World War II: Malmedy Massacre - Murder of American POWs Investigation & Trial Documents

World War II: Malmedy Massacre - Murder of American POWs Investigation & Trial Documents

6,842 pages of documents related to The Malmedy Massacre, a war crime committed by members of Kampfgruppe Peiper (part of the 1st SS Panzer Division), a German combat unit led by Joachim Peiper, at Baugnez crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium, on December 17, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge.

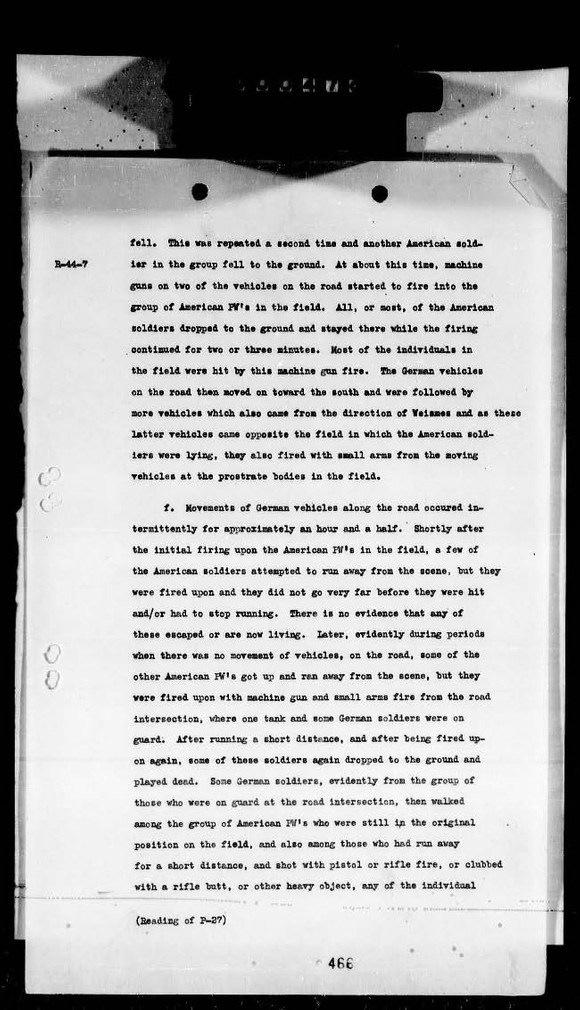

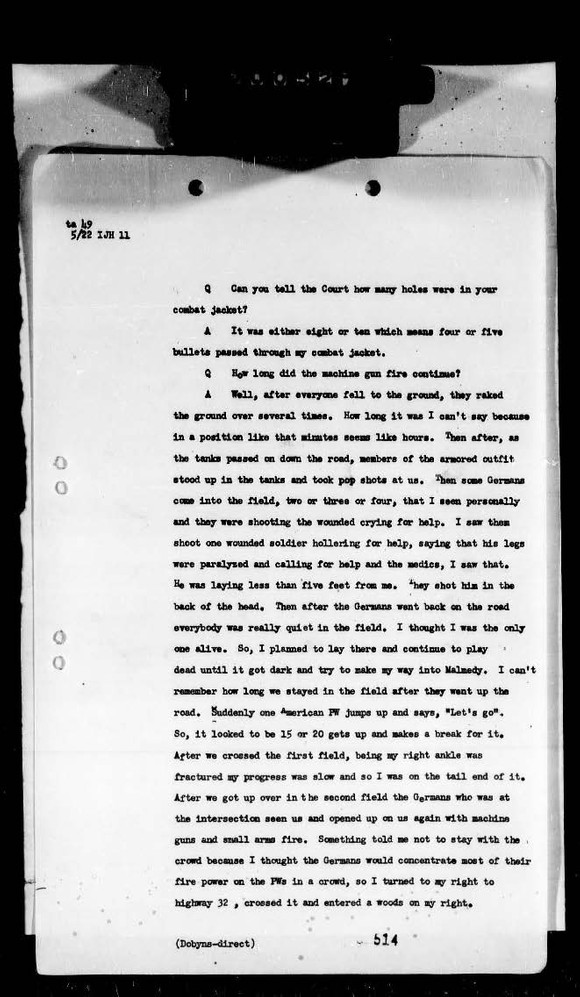

On December 16, 1944, the German Army began the Ardennes offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge. On December 17, 113 American soldiers surrendered to a German armored column under the command of SS Colonel Joachim Peiper [variant: Piper]. After the American prisoners were disarmed, they were assembled in a field near Malmedy, Belgium, and shot. Several weeks after the “Malmedy Massacre,” even more American POWs and a smaller number of Belgian civilians were also shot and killed by German troops during the Ardennes Offensive, commonly known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Seventy-four Germans were later tried by a U.S. military government court for the murders committed at Malmedy and other locations between 16 December 1944 and 13 January 1945. Seventy-three were eventually found guilty following the trial, which began on 16 May 1946, at Dachau, Germany. Forty-three were sentenced to be hanged; twenty-two received life imprisonment; and the remainder were sentenced to jail terms between ten and twenty years. However, no one was put to death, and by Christmas 1956, all the convicted men had been released from prison.

In March 1949, in response to charges alleging unfair conduct by the prosecution in the Malmedy cases, the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services appointed a subcommittee to review the Army’s investigative and trial procedures. The Hon. Raymond E. Baldwin, chairman, presided over the subcommittee hearings, which were held in April, May, June, and September 1949. The subcommittee report was released by the full committee on October 13, 1949.

In 1976 while living in France, Joachim Peiper was killed. It is believed that he was killed by either former World War II era Communist resistance members or former French Resistance Members.

The two main sections of this collection are the Malmedy Massacre Record of Trial and the Congressional Hearings.

Malmedy Massacre Record of Trial

5,154 pages of transcripts of trial proceedings.

On 16 May 1946, some seventeen months after the killings at Malmedy, a “military government court” consisting of eight officers and convened by Headquarters, U.S. Third Army, began hearing evidence against the Germens accused. While styled as a military government court in the convening orders, the tribunal was more akin to a military commission in that it operated with relaxed rules of evidence and procedure (e.g., hearsay was admissible and there was no presumption of innocence) and required only a two-thirds majority for a death sentence.

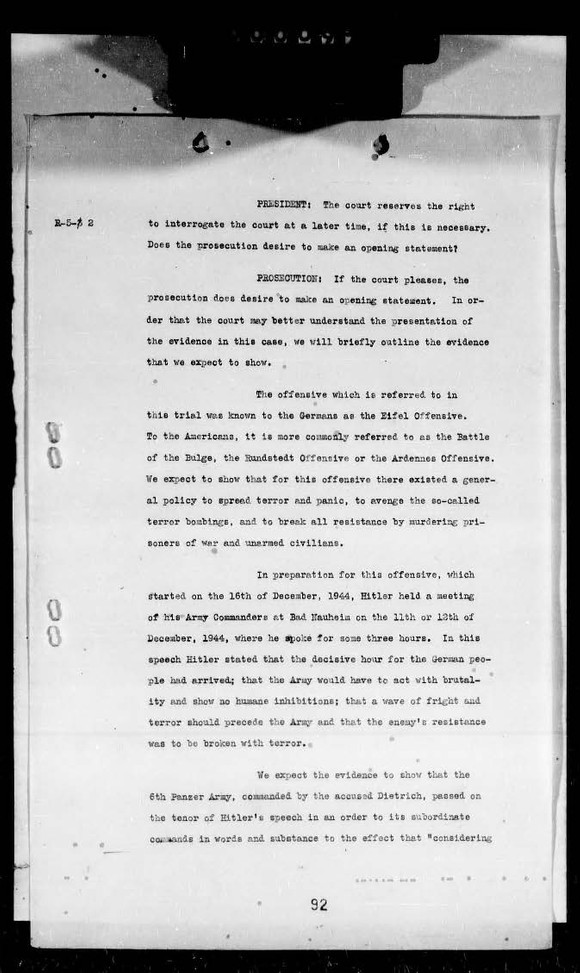

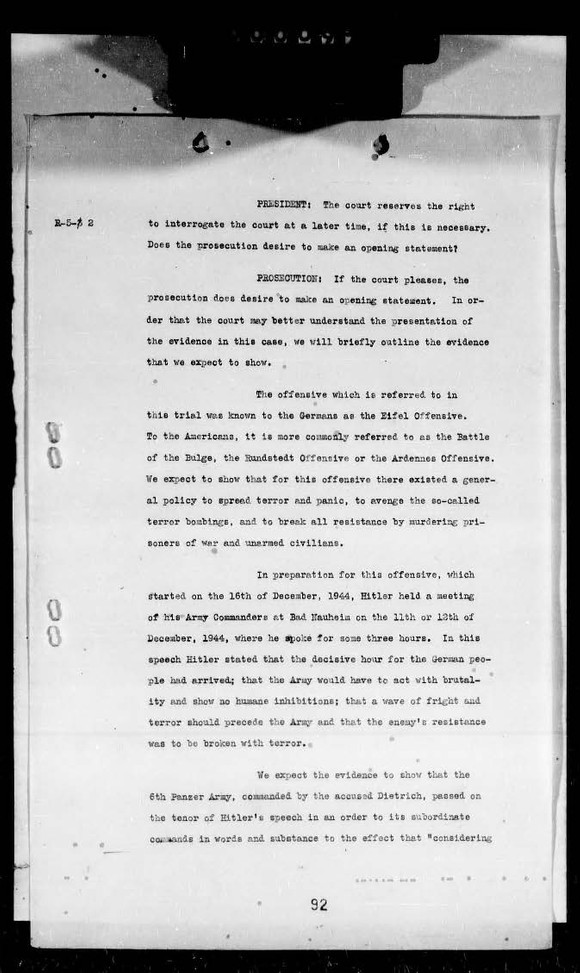

The court proceedings, held in Dachau within sight of the infamous concentration camp of the same name, began with Chief Prosecutor Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Burton F. Ellis’s opening statement and his assertion that the Government would prove that “538 to 749” American POWs and “over 90” Belgian civilians had been murdered.

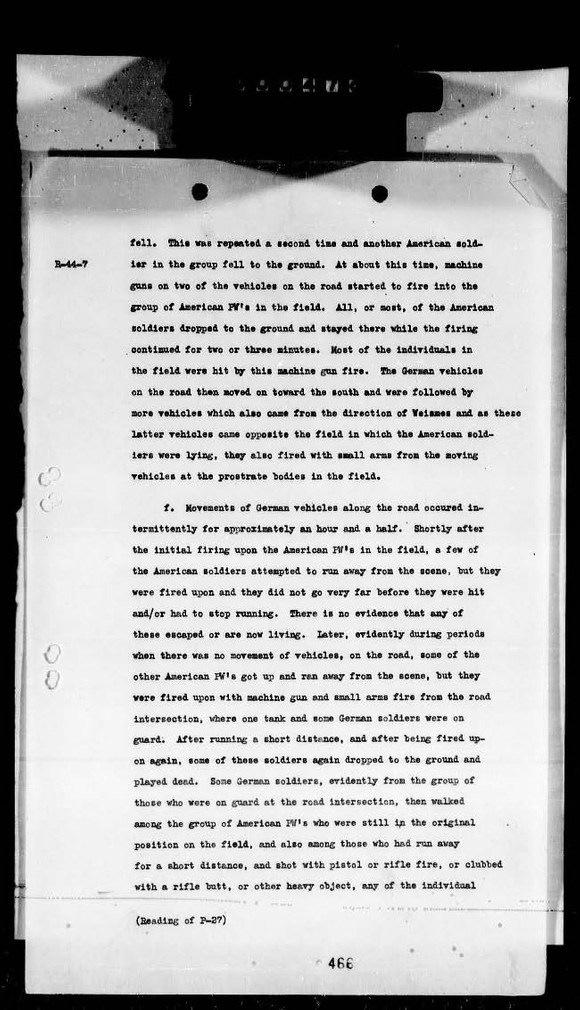

Over the next three weeks, the prosecution called members of Peiper’s Kampfgruppe, who had not been charged with crimes, to testify that Peiper and other SS officers and noncommissioned officers had instructed their men to ignore the rules of war governing prisoners. For example, SS Private First Class Fritz Geiberger stated under oath that his platoon leader had given “a blanket order requiring the shooting of prisoners of war.” SS-Corporal Ernst Kohler testified that his platoon was ordered to “show no mercy to Belgian civilians” and to “take no prisoners,” as this would avenge German women and children killed in Allied air raids.

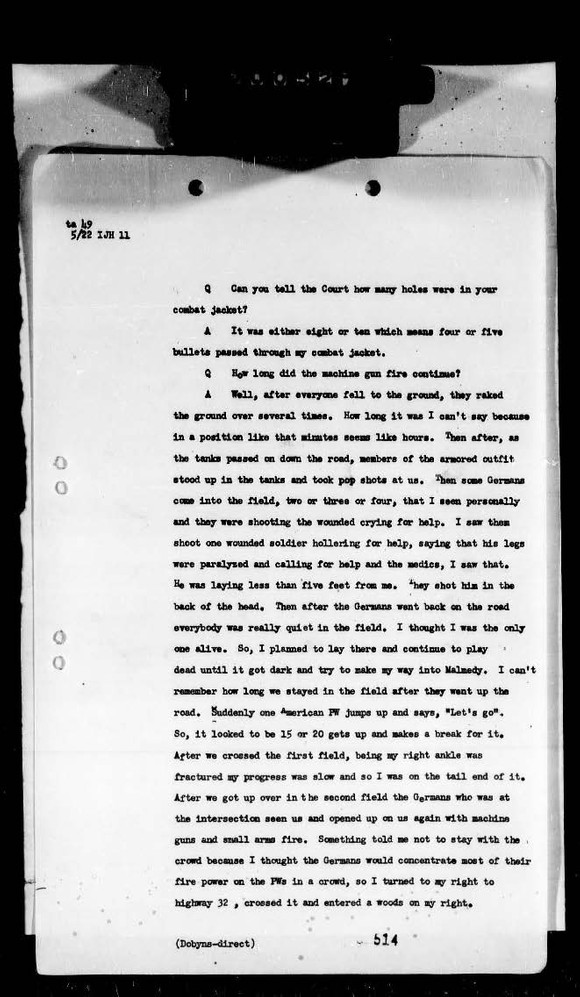

Additional testimony came from Malmedy survivors 1LT Lary and an ex-military policeman named Homer Ford, who had heard the American wounded “moaning and crying” and watched the Germans “either shoot them or hit them with the butts of their guns.” Several Belgian civilians also declared under oath that they had witnessed the brutal and unjustified killing of unarmed civilians by SS troops. The testimony, especially of the German witnesses, was designed to prove that the killing of the American POWs and Belgian civilians was premeditated because it had been part of a conspiracy or common design.

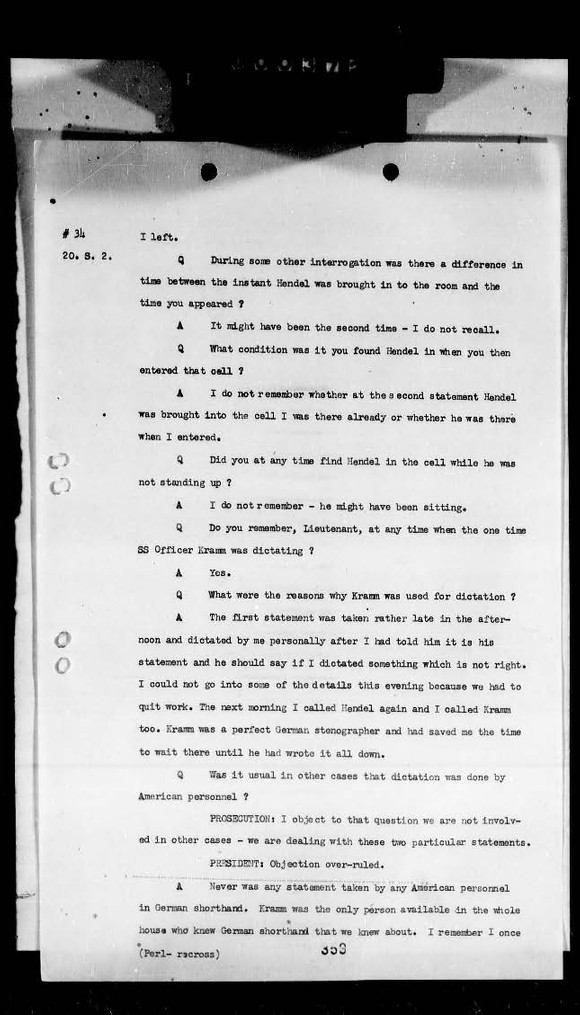

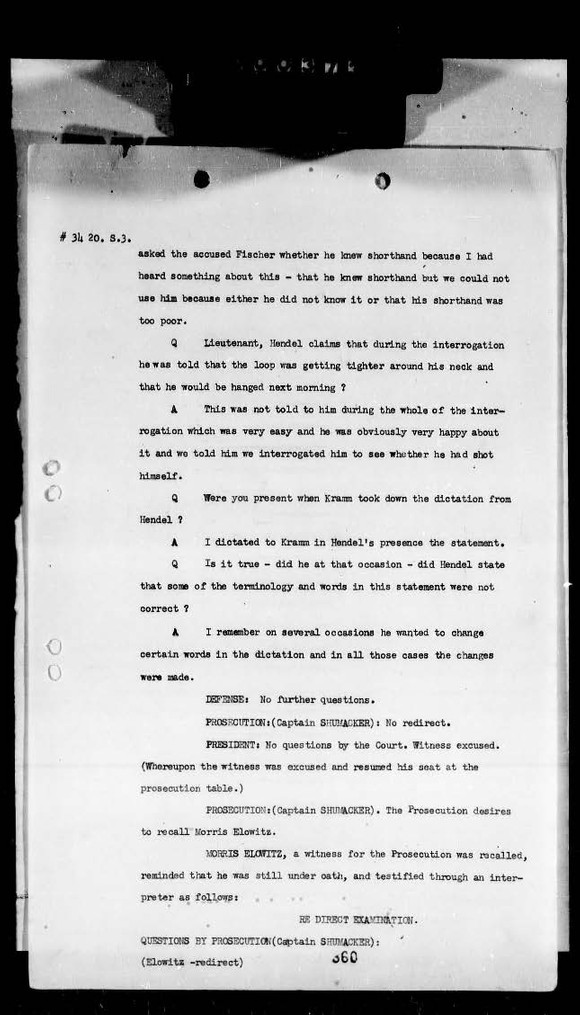

The bulk of the prosecution’s evidence, however, was not live testimony. Nearly one hundred written sworn statements linked each of the SS accused with crimes that were described in exhaustive detail.

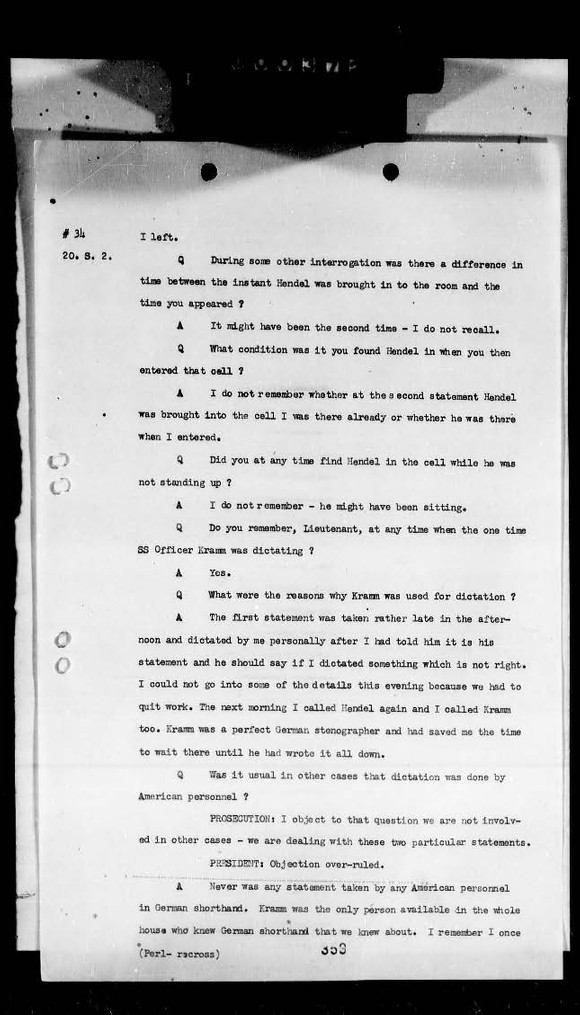

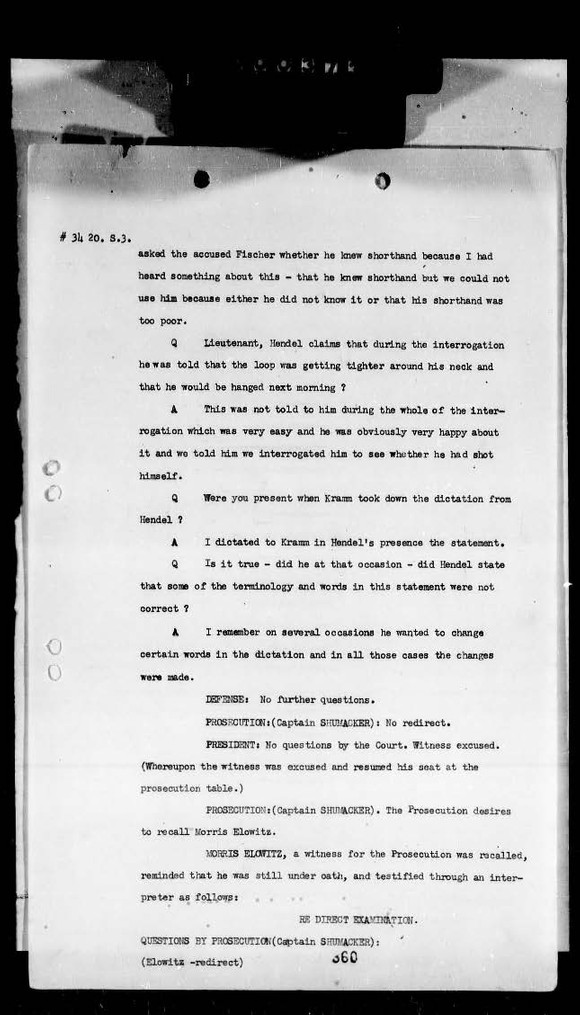

COL Willis M. Everett, Jr., who was in charge of the defense and the defense counsel soon learned however, that there were problems with some of the sworn statements. Their German clients insisted that many of their statements were the result of trickery, deceit, and in some cases, coercion. Peiper claimed that one of his fellow accused had been beaten for nearly an hour by American investigators seeking a confession—although apparently no incriminating statement was obtained. Two other Germens accused claimed that ropes had been placed around their necks during questioning. This act, they believed, was preparatory to hanging.

However, the most prevalent interrogation technique that had been the use of a “mock trial,” where the accused was brought before a one-person tribunal. While he sat with his “defense counsel,” the “court” rushed through the proceedings before informing the surprised accused that he was to be hanged the next day, so he “might as well write up a confession and clear some of his other fellow accused, seeing that he would be hanged." How many sworn statements were obtained through the use of these fake tribunals, which Army investigators admitted they had used at times, and which they called a “schnell (or fast) procedure,” is not known, but no doubt some of the statements introduced at trial resulted from their use. On the other hand, as some statements from the SS accused had been obtained after “one or two brief and straightforward interrogation sessions,” it is equally true that subsequent claims of widespread coercive interrogation were not proved.

Everett was sufficiently alarmed by his clients’ claims of abuse to report the alleged prosecutorial misconduct to COL Claude B. Mickelwaite, the Deputy Theater Judge Advocate in Wiesbaden, Germany. Mickelwaite, who had overall responsibility for the prosecution of war crimes in Germany, sent a subordinate, LTC Edwin Carpenter, to Dachau to investigate. Carpenter concluded that mock courts and other psychological stratagems had, in fact, been used by Army investigators, but Carpenter also concluded that none of the sworn statements obtained from the accused were the product of physical violence.

After the prosecution rested, the defense presented its evidence. Everett argued that the Malmedy massacre was an unfortunate event that had occurred during fastmoving and very fluid combat operations during the Battle of the Bulge. To support his argument, Everett called several German officers to testify that there had been no formal orders to murder POWs. Everett also managed to locate a West Point graduate and regular Army officer, LTC Harold D. McCown, who testified under oath that he had been captured by Peiper’s Kampfgruppe and had been well treated while a POW. Everett and his defense team also argued that the nearly one hundred sworn statements introduced into evidence by the prosecution were unreliable products of coercion.

On 11 July 1946, after a two-month trial, BG Dalbey and the panel retired to consider the evidence. Two hours and twenty minutes later, they were back with a verdict: All seventy-three accused were found guilty of the “killing, shooting, ill-treatment, abuse and torture of members of the armed forces of the United States of America and of

unarmed Allied civilians.”

On July 16, 1946, the panel announced that forty-three convicted SS troops, including Peiper, were sentenced to death. Twenty-two received life sentences, and the rest were sentenced to jail terms of ten to twenty years.

Recognizing that there was no formal avenue of appeal from the Malmedy verdict, Everett instead began a vocal and public letter writing campaign. Everett argued that “80 to 90 percent of the confessions had been obtained illegally” and that this prosecutorial misconduct had deprived justice to Peiper and his seventy-two fellow SS-troops. Everett also insisted that it had been impossible for him and his team to mount an effective defense because the court’s desire for vengeance made the Malmedy verdict a foregone conclusion.

In the meantime, COL James L. Harbaugh, the European Command (EUCOM) Staff Judge Advocate, was reviewing the Malmedy record of trial and preparing a recommendation for General Lucius Clay, then serving as Military Governor of the American Zone of Occupation (Germany). Harbaugh’s legal review concluded that the evidence was insufficient to sustain some convictions and that many of the death sentences were inappropriate. As a result, on March 20, 1948, GEN Clay reduced thirty-one of the forty-three death sentences to life imprisonment, but confirmed the remaining twelve death sentences, including Peiper’s. General Clay also disapproved the findings in several cases, which freed thirteen other men.

Secretary of War Royall decided to form a commission to look at all the death penalty cases tried at the trial. The Simpson commission concluded in September 1948 that the war crimes trials being conducted in Germany were “essentially fair” and that there was no “systematic use of improper methods to secure prosecution evidence.”

However, the Malmedy trial was different; the use of mock trials had cast “sufficient doubt” on the proceedings to make it “unwise” to carry out the remaining death sentences.

Shortly after the Simpson commission delivered its report to Secretary Royall, a Senate Armed Services Committee subcommittee chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin began hearings on the Malmedy case.

Congressional Hearings

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services Part 1 April 18 - June 6, 1949 - Transcripts of the investigation hearing taking place on April 18, 20, 22, 29, May 4-6, 9-13, 16-20, 23, 24, June 1-3, 6, 1949.

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services Part 2: September 5 -September 28, 1949 - Transcripts and Exhibits of the investigation hearing taking place on September 5-8,13, and 28, 1949.

Report of Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services October 13, 1949 - This report was presented to the Committee on Armed Services by the subcommittee chairman, Senator Raymond E. Baldwin, at the committee meeting on October 13. The report was unanimously approved by the committee and Senator Baldwin thereupon presented it to the Senate on October 14, 1949.

A Senate Armed Services Committee subcommittee chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin convened hearings on the Malmedy case. Beginning in March 1949, the subcommittee heard from 108 witnesses

and examined thousands of pages of documents. Baldwin also invited Senator Joseph McCarthy to participate as a visiting member of the subcommittee. McCarthy’s participation was intended to “gain additional credibility and quiet the more radical Army critics,” but Baldwin may have regretted this move. McCarthy dominated the subcommittee hearings for almost a month and sharply attacked the Army. McCarthy had a particularly heated confrontation with now COL Ellis, whom McCarthy accused of grave misconduct at the Malmedy trial.

In October 1949, the subcommittee published its report. It unanimously concluded that the allegations of physical mistreatment and torture were false and that the claims that violence had been used to obtain confessions were without merit. However, the report did find that Army investigators had employed mock trials “in not more than 12 cases of the several hundred suspects interrogated by the war crimes investigative teams.” The subcommittee criticized these mock trials as a “grave mistake” because the use of psychological trickery was unnecessary and had ultimately been exploited by critics of the war crimes trial program. Significantly, the subcommittee found that “American authorities have unquestionably leaned over backward in reviewing any cases affected by the mock trials. . . . [I]t appears many sentences have been commuted that otherwise might not have been changed.”

On 31 January 1951, General Thomas T. Handy commuted the death sentences of Peiper and the remaining Malmedy accused. By Christmas 1956, all the Malmedy accused had been released from prison.

Other materials include:

The Malmedy Massacre Trial: The Military Government Court Proceedings and the Controversial Legal Aftermath (2012)

An article by Fred L. Borch, III, Regimental Historian and Archivist for the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps, appearing in the March 2012 issue of the journal The Amy Lawyer. Provides a summary of the trial and its aftermath.

6,842 pages of documents related to The Malmedy Massacre, a war crime committed by members of Kampfgruppe Peiper (part of the 1st SS Panzer Division), a German combat unit led by Joachim Peiper, at Baugnez crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium, on December 17, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge.

On December 16, 1944, the German Army began the Ardennes offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge. On December 17, 113 American soldiers surrendered to a German armored column under the command of SS Colonel Joachim Peiper [variant: Piper]. After the American prisoners were disarmed, they were assembled in a field near Malmedy, Belgium, and shot. Several weeks after the “Malmedy Massacre,” even more American POWs and a smaller number of Belgian civilians were also shot and killed by German troops during the Ardennes Offensive, commonly known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Seventy-four Germans were later tried by a U.S. military government court for the murders committed at Malmedy and other locations between 16 December 1944 and 13 January 1945. Seventy-three were eventually found guilty following the trial, which began on 16 May 1946, at Dachau, Germany. Forty-three were sentenced to be hanged; twenty-two received life imprisonment; and the remainder were sentenced to jail terms between ten and twenty years. However, no one was put to death, and by Christmas 1956, all the convicted men had been released from prison.

In March 1949, in response to charges alleging unfair conduct by the prosecution in the Malmedy cases, the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services appointed a subcommittee to review the Army’s investigative and trial procedures. The Hon. Raymond E. Baldwin, chairman, presided over the subcommittee hearings, which were held in April, May, June, and September 1949. The subcommittee report was released by the full committee on October 13, 1949.

In 1976 while living in France, Joachim Peiper was killed. It is believed that he was killed by either former World War II era Communist resistance members or former French Resistance Members.

The two main sections of this collection are the Malmedy Massacre Record of Trial and the Congressional Hearings.

Malmedy Massacre Record of Trial

5,154 pages of transcripts of trial proceedings.

On 16 May 1946, some seventeen months after the killings at Malmedy, a “military government court” consisting of eight officers and convened by Headquarters, U.S. Third Army, began hearing evidence against the Germens accused. While styled as a military government court in the convening orders, the tribunal was more akin to a military commission in that it operated with relaxed rules of evidence and procedure (e.g., hearsay was admissible and there was no presumption of innocence) and required only a two-thirds majority for a death sentence.

The court proceedings, held in Dachau within sight of the infamous concentration camp of the same name, began with Chief Prosecutor Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Burton F. Ellis’s opening statement and his assertion that the Government would prove that “538 to 749” American POWs and “over 90” Belgian civilians had been murdered.

Over the next three weeks, the prosecution called members of Peiper’s Kampfgruppe, who had not been charged with crimes, to testify that Peiper and other SS officers and noncommissioned officers had instructed their men to ignore the rules of war governing prisoners. For example, SS Private First Class Fritz Geiberger stated under oath that his platoon leader had given “a blanket order requiring the shooting of prisoners of war.” SS-Corporal Ernst Kohler testified that his platoon was ordered to “show no mercy to Belgian civilians” and to “take no prisoners,” as this would avenge German women and children killed in Allied air raids.

Additional testimony came from Malmedy survivors 1LT Lary and an ex-military policeman named Homer Ford, who had heard the American wounded “moaning and crying” and watched the Germans “either shoot them or hit them with the butts of their guns.” Several Belgian civilians also declared under oath that they had witnessed the brutal and unjustified killing of unarmed civilians by SS troops. The testimony, especially of the German witnesses, was designed to prove that the killing of the American POWs and Belgian civilians was premeditated because it had been part of a conspiracy or common design.

The bulk of the prosecution’s evidence, however, was not live testimony. Nearly one hundred written sworn statements linked each of the SS accused with crimes that were described in exhaustive detail.

COL Willis M. Everett, Jr., who was in charge of the defense and the defense counsel soon learned however, that there were problems with some of the sworn statements. Their German clients insisted that many of their statements were the result of trickery, deceit, and in some cases, coercion. Peiper claimed that one of his fellow accused had been beaten for nearly an hour by American investigators seeking a confession—although apparently no incriminating statement was obtained. Two other Germens accused claimed that ropes had been placed around their necks during questioning. This act, they believed, was preparatory to hanging.

However, the most prevalent interrogation technique that had been the use of a “mock trial,” where the accused was brought before a one-person tribunal. While he sat with his “defense counsel,” the “court” rushed through the proceedings before informing the surprised accused that he was to be hanged the next day, so he “might as well write up a confession and clear some of his other fellow accused, seeing that he would be hanged." How many sworn statements were obtained through the use of these fake tribunals, which Army investigators admitted they had used at times, and which they called a “schnell (or fast) procedure,” is not known, but no doubt some of the statements introduced at trial resulted from their use. On the other hand, as some statements from the SS accused had been obtained after “one or two brief and straightforward interrogation sessions,” it is equally true that subsequent claims of widespread coercive interrogation were not proved.

Everett was sufficiently alarmed by his clients’ claims of abuse to report the alleged prosecutorial misconduct to COL Claude B. Mickelwaite, the Deputy Theater Judge Advocate in Wiesbaden, Germany. Mickelwaite, who had overall responsibility for the prosecution of war crimes in Germany, sent a subordinate, LTC Edwin Carpenter, to Dachau to investigate. Carpenter concluded that mock courts and other psychological stratagems had, in fact, been used by Army investigators, but Carpenter also concluded that none of the sworn statements obtained from the accused were the product of physical violence.

After the prosecution rested, the defense presented its evidence. Everett argued that the Malmedy massacre was an unfortunate event that had occurred during fastmoving and very fluid combat operations during the Battle of the Bulge. To support his argument, Everett called several German officers to testify that there had been no formal orders to murder POWs. Everett also managed to locate a West Point graduate and regular Army officer, LTC Harold D. McCown, who testified under oath that he had been captured by Peiper’s Kampfgruppe and had been well treated while a POW. Everett and his defense team also argued that the nearly one hundred sworn statements introduced into evidence by the prosecution were unreliable products of coercion.

On 11 July 1946, after a two-month trial, BG Dalbey and the panel retired to consider the evidence. Two hours and twenty minutes later, they were back with a verdict: All seventy-three accused were found guilty of the “killing, shooting, ill-treatment, abuse and torture of members of the armed forces of the United States of America and of

unarmed Allied civilians.”

On July 16, 1946, the panel announced that forty-three convicted SS troops, including Peiper, were sentenced to death. Twenty-two received life sentences, and the rest were sentenced to jail terms of ten to twenty years.

Recognizing that there was no formal avenue of appeal from the Malmedy verdict, Everett instead began a vocal and public letter writing campaign. Everett argued that “80 to 90 percent of the confessions had been obtained illegally” and that this prosecutorial misconduct had deprived justice to Peiper and his seventy-two fellow SS-troops. Everett also insisted that it had been impossible for him and his team to mount an effective defense because the court’s desire for vengeance made the Malmedy verdict a foregone conclusion.

In the meantime, COL James L. Harbaugh, the European Command (EUCOM) Staff Judge Advocate, was reviewing the Malmedy record of trial and preparing a recommendation for General Lucius Clay, then serving as Military Governor of the American Zone of Occupation (Germany). Harbaugh’s legal review concluded that the evidence was insufficient to sustain some convictions and that many of the death sentences were inappropriate. As a result, on March 20, 1948, GEN Clay reduced thirty-one of the forty-three death sentences to life imprisonment, but confirmed the remaining twelve death sentences, including Peiper’s. General Clay also disapproved the findings in several cases, which freed thirteen other men.

Secretary of War Royall decided to form a commission to look at all the death penalty cases tried at the trial. The Simpson commission concluded in September 1948 that the war crimes trials being conducted in Germany were “essentially fair” and that there was no “systematic use of improper methods to secure prosecution evidence.”

However, the Malmedy trial was different; the use of mock trials had cast “sufficient doubt” on the proceedings to make it “unwise” to carry out the remaining death sentences.

Shortly after the Simpson commission delivered its report to Secretary Royall, a Senate Armed Services Committee subcommittee chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin began hearings on the Malmedy case.

Congressional Hearings

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services Part 1 April 18 - June 6, 1949 - Transcripts of the investigation hearing taking place on April 18, 20, 22, 29, May 4-6, 9-13, 16-20, 23, 24, June 1-3, 6, 1949.

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services Part 2: September 5 -September 28, 1949 - Transcripts and Exhibits of the investigation hearing taking place on September 5-8,13, and 28, 1949.

Report of Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services October 13, 1949 - This report was presented to the Committee on Armed Services by the subcommittee chairman, Senator Raymond E. Baldwin, at the committee meeting on October 13. The report was unanimously approved by the committee and Senator Baldwin thereupon presented it to the Senate on October 14, 1949.

A Senate Armed Services Committee subcommittee chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin convened hearings on the Malmedy case. Beginning in March 1949, the subcommittee heard from 108 witnesses

and examined thousands of pages of documents. Baldwin also invited Senator Joseph McCarthy to participate as a visiting member of the subcommittee. McCarthy’s participation was intended to “gain additional credibility and quiet the more radical Army critics,” but Baldwin may have regretted this move. McCarthy dominated the subcommittee hearings for almost a month and sharply attacked the Army. McCarthy had a particularly heated confrontation with now COL Ellis, whom McCarthy accused of grave misconduct at the Malmedy trial.

In October 1949, the subcommittee published its report. It unanimously concluded that the allegations of physical mistreatment and torture were false and that the claims that violence had been used to obtain confessions were without merit. However, the report did find that Army investigators had employed mock trials “in not more than 12 cases of the several hundred suspects interrogated by the war crimes investigative teams.” The subcommittee criticized these mock trials as a “grave mistake” because the use of psychological trickery was unnecessary and had ultimately been exploited by critics of the war crimes trial program. Significantly, the subcommittee found that “American authorities have unquestionably leaned over backward in reviewing any cases affected by the mock trials. . . . [I]t appears many sentences have been commuted that otherwise might not have been changed.”

On 31 January 1951, General Thomas T. Handy commuted the death sentences of Peiper and the remaining Malmedy accused. By Christmas 1956, all the Malmedy accused had been released from prison.

Other materials include:

The Malmedy Massacre Trial: The Military Government Court Proceedings and the Controversial Legal Aftermath (2012)

An article by Fred L. Borch, III, Regimental Historian and Archivist for the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps, appearing in the March 2012 issue of the journal The Amy Lawyer. Provides a summary of the trial and its aftermath.

1 file (451.5MB)