Starting from:

$12.95

World War II: Eddie Slovik Court Martial and Execution Documents - Download

World War II: Eddie Slovik Court Martial and Execution Documents

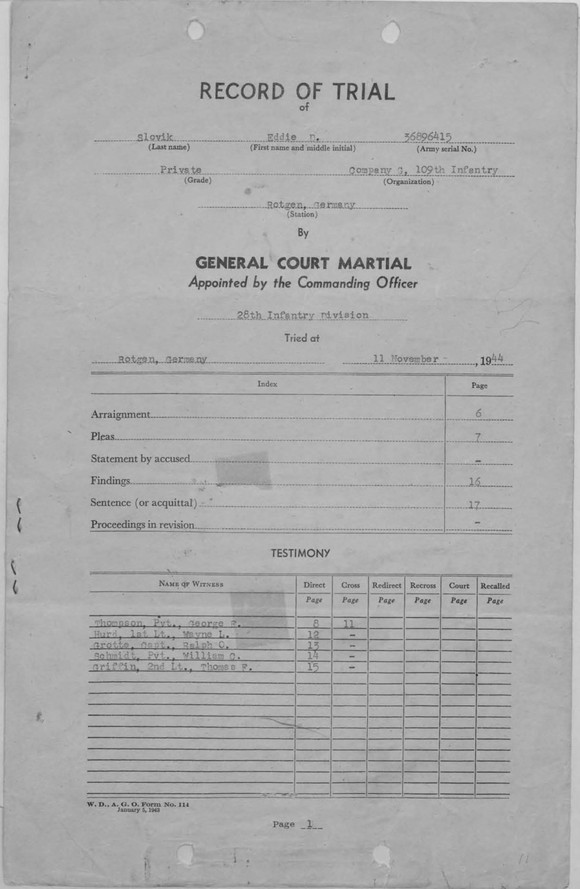

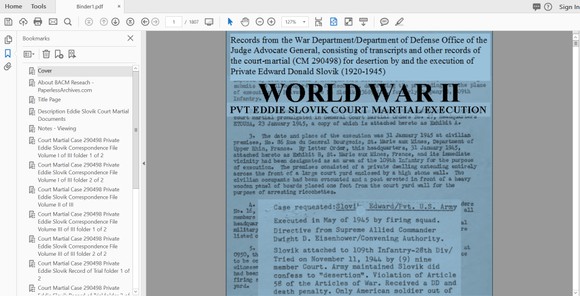

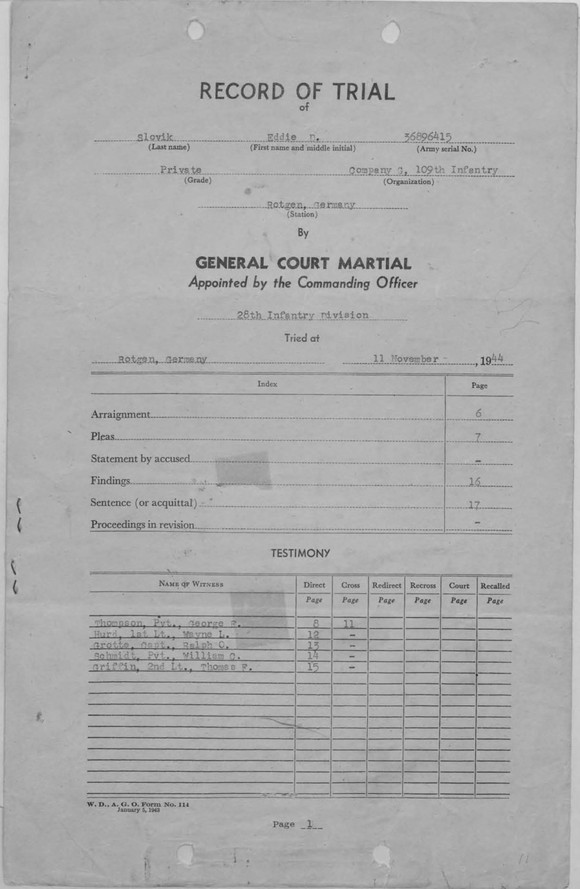

1,776 pages of records from the War Department/Department of Defense Office of the Judge Advocate General, consisting of transcripts and other records of the court-martial (CM 290498) for desertion by and the execution of Private Edward Donald Slovik (1920-1945).

This collection includes a case file of the court-martial of Private Eddie Slovik, and related correspondences, compiled from 1944 to 1981. Arranged in three parts: the case file, correspondence, and a copy of "Liberty" magazine. The records include Slovik's handwritten confession, affidavits, exhibits, general orders, case reviews, a copy of Slovik's civilian criminal record from the FBI and reports relating the details of his execution. The collection includes folders of correspondence from individuals commenting on or seeking information about the case. Also included is a copy of "Liberty" magazine mentioning the Slovik case.

Additional Material includes:

Eddie D. Slovik Pardon File – 77 pages of documents related to the estate of Eddie D. Slovik's petition for a posthumous pardon from President Clinton.

Eddie D. Slovik Official Military Personnel File - 597-page, Official Military Personnel File includes records from the following folders: Service Documents (January 1944-April 1981); Field File/Jacket or Record Book (January 1944-January 1945); Correspondence (June 1944-December 1976); Medical Records (November 1944-January 1945); Disciplinary (November 1944-January 1945); Original Containers (n.d.).

A copy of the 22-page War Department field manual for executions: War Department Pamphlet No. 27-4 Procedure for Military Executions 12 June 1944.

BACKGROUND

During World War II, approximately 40,000 soldiers deserted. Of these, 2,864 were tried by general courts-martial, and 49 death sentences were handed down. Forty-eight of the death sentences were commuted.

“Squad, ready. Aim. FIRE.” With that last command, a party of twelve American Soldiers fired their rifles at an Army private tied to a wooden post. It was 31 January 1945 and Private Eddie D. Slovik, his head covered by a black hood as required by military regulations, was killed. According to William Bradford Huie, author of "The Execution of Private Slovik," his death by firing squad in France was the only execution of an American for a purely military offense since the Civil War.

From the end of the American Civil War until World War II, no American soldier was executed for cowardice or desertion, even during wartime. This period included twenty-five years of conflict on the frontier with American Indians, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, World War I, and a number of interventions and expeditions in Latin America. Until World War II, the U.S. Army punished deserters with imprisonment, fines, loss of pay and benefits, and dishonorable discharge.

Slovik was born in Detroit, Michigan in February 1920. He grew up in a poor home environment. Slovik quit school at the age of fifteen and was repeatedly in trouble with the law. In the late 1930s, Slovik was convicted of embezzlement and sentenced to six months to ten years in prison.

Slovik was still incarcerated when the United States entered World War II and, when he was released in April 1942 he was given the classification “4-F” as an ex-convict. This meant he had initially escaped the draft, as the Army had sufficient manpower and did not need to draft convicted felons. In late 1943, however, facing an increased need for able-bodied young men, the War Department reclassified Slovik as “I-A” defining him as available and fit for general military service. Slovik was soon after inducted into the Army.

After completing basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, PVT Slovik shipped out to Europe in August 1944. Assigned to the 109th Infantry Regiment, a part of the Pennsylvania National Guard 28th Infantry Division, Slovik and other replacements were on their way to their unit in Elbeuf, France, when they were attacked by German forces. Slovik intentionally avoided combat and walked away. He then joined up with a Canadian unit and did odd jobs, including cooking, for the next forty-five days. Slovik was returned to U.S. authorities on 4 October 1944 and reported back to the 109th Infantry three days later.

When questioned by his company commander, Captain (CPT) Ralph O. Grotte, about this absence, Slovik told Grotte that he was “too scared, too nervous” to serve with a rifle company and would desert again if ordered to fight (William B. Huie, The Execution of Private Slovik (1970) supra note 1, at page 127).

Slovik was then ordered to remain in the company area. Shortly thereafter, he returned to CPT Grotte and asked: “If I leave now, will it be desertion?” When Grotte said yes, Slovik left without his weapon. The next day, PVT Slovik surrendered to a nearby unit and handed a cook a signed, hand-printed note that said, in part: "I Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik confess to the Desertion of the United States Army. . . . I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out their again Id run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND ILL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THEIR," (Id. at 128).

After being returned to the 109th Infantry on 9 October, Slovik’s commander told him that the written note was damaging to his case and that he should take it back and destroy it. Slovik refused and was confined to the division stockade.

On 19 October, Slovik was charged with two specifications of desertion, in violation of the 58th Article of War. Both specifications alleged that he deserted “with intent to shirk hazardous duty and shirk important action, to wit: action against the enemy” on two different occasions: his forty-five day desertion from 25 August to 4 October 1944 and his one-day desertion from 8 to 9 October 1944.

On 26 October, Lieutenant Colonel Henry P. Sommer, the division judge advocate, offered Slovik a deal: if he would go into the line, that is, accept a combat assignment, he could escape court-martial. Slovik refused this offer and on 29 October his case was referred to trial by general court-martial.

On 11 November 1944, Slovik was tried for desertion. He pleaded not guilty and elected to remain silent. At the end of a two-hour trial, a nine-member panel found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. After Slovik was confined to the Army stockade in Paris, France, Sommer reviewed the record of trial. He recommended to Major General Norman “Dutch” Cota, the division commander, that the findings and sentence be approved. Cota approved the findings and sentence on 27 November.

From 1 December 1944 to 6 January 1945, Brigadier General E. C. McNeil, the senior Army lawyer in the European Theater, and lawyers on McNeil’s staff, reviewed Slovik’s case. McNeil wrote: "This is the first death sentence for desertion which has reached me for examination. It is probably the first of its kind in the American Army for over eighty years; there were none in World War I. In this case, the extreme penalty of death appears warranted. This soldier had performed no front-line duty. He deserted from his group of about fifteen when about to join the infantry company to which he had been assigned. His subsequent conduct shows a deliberate plan to secure trial and incarceration in a safe place. The sentence adjudged was more severe than he anticipated, but the imposition of a less severe sentence would only have accomplished the accused’s purpose in securing his incarceration and consequent freedom from the dangers which so many of our armed forces are required to face daily. His unfavorable civilian record indicates that he is not a worthy subject of clemency."

On 23 January 1945, General Eisenhower ordered Slovik’s execution by firing squad and directed that the shooting occur in the 109th’s “regimental area.” It should be noted that General Eisenhower did not simply decline to intervene in the Slovik case.

While 142 American Soldiers were executed for murder and/or rape during World War II, Slovik’s was the only execution for desertion in the face of the enemy.

In the years after Slovik’s death, his widow campaigned relentlessly for his records to be changed so that she could receive the proceeds of his $10,000 life insurance policy. While many were sympathetic, she and her supporters were unsuccessful. Today, most historians believe that Slovik might have escaped a firing squad had his timing been better. However, the 28th Infantry Division was engaged in bloody fighting in Huertgen Forest at the time of his trial, and the court-martial panel was in no mood for leniency. Additionally, when Eisenhower acted on Slovik’s case, the Battle of the Bulge was raging, and American forces were in serious trouble in the face of a German surprise offensive. Eisenhower likely saw that any value of leniency was outweighed by the view that maintaining discipline in the face of the enemy required that Slovik be executed.

Sources:

"Lore of the Corps - Shot by Firing Squad: The Trial and Execution of Pvt. Eddie Slovik" by Fred L. Borch III, The Army Lawyer May 2010

"The Execution of Private Eddie D. Slovik "by Dr. Jerold E. Brown, Combined Arms Battle Since 1939 (1992)

William Bradford Huie, "The Execution of Private Slovik" (1970)

1,776 pages of records from the War Department/Department of Defense Office of the Judge Advocate General, consisting of transcripts and other records of the court-martial (CM 290498) for desertion by and the execution of Private Edward Donald Slovik (1920-1945).

This collection includes a case file of the court-martial of Private Eddie Slovik, and related correspondences, compiled from 1944 to 1981. Arranged in three parts: the case file, correspondence, and a copy of "Liberty" magazine. The records include Slovik's handwritten confession, affidavits, exhibits, general orders, case reviews, a copy of Slovik's civilian criminal record from the FBI and reports relating the details of his execution. The collection includes folders of correspondence from individuals commenting on or seeking information about the case. Also included is a copy of "Liberty" magazine mentioning the Slovik case.

Additional Material includes:

Eddie D. Slovik Pardon File – 77 pages of documents related to the estate of Eddie D. Slovik's petition for a posthumous pardon from President Clinton.

Eddie D. Slovik Official Military Personnel File - 597-page, Official Military Personnel File includes records from the following folders: Service Documents (January 1944-April 1981); Field File/Jacket or Record Book (January 1944-January 1945); Correspondence (June 1944-December 1976); Medical Records (November 1944-January 1945); Disciplinary (November 1944-January 1945); Original Containers (n.d.).

A copy of the 22-page War Department field manual for executions: War Department Pamphlet No. 27-4 Procedure for Military Executions 12 June 1944.

BACKGROUND

During World War II, approximately 40,000 soldiers deserted. Of these, 2,864 were tried by general courts-martial, and 49 death sentences were handed down. Forty-eight of the death sentences were commuted.

“Squad, ready. Aim. FIRE.” With that last command, a party of twelve American Soldiers fired their rifles at an Army private tied to a wooden post. It was 31 January 1945 and Private Eddie D. Slovik, his head covered by a black hood as required by military regulations, was killed. According to William Bradford Huie, author of "The Execution of Private Slovik," his death by firing squad in France was the only execution of an American for a purely military offense since the Civil War.

From the end of the American Civil War until World War II, no American soldier was executed for cowardice or desertion, even during wartime. This period included twenty-five years of conflict on the frontier with American Indians, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, World War I, and a number of interventions and expeditions in Latin America. Until World War II, the U.S. Army punished deserters with imprisonment, fines, loss of pay and benefits, and dishonorable discharge.

Slovik was born in Detroit, Michigan in February 1920. He grew up in a poor home environment. Slovik quit school at the age of fifteen and was repeatedly in trouble with the law. In the late 1930s, Slovik was convicted of embezzlement and sentenced to six months to ten years in prison.

Slovik was still incarcerated when the United States entered World War II and, when he was released in April 1942 he was given the classification “4-F” as an ex-convict. This meant he had initially escaped the draft, as the Army had sufficient manpower and did not need to draft convicted felons. In late 1943, however, facing an increased need for able-bodied young men, the War Department reclassified Slovik as “I-A” defining him as available and fit for general military service. Slovik was soon after inducted into the Army.

After completing basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, PVT Slovik shipped out to Europe in August 1944. Assigned to the 109th Infantry Regiment, a part of the Pennsylvania National Guard 28th Infantry Division, Slovik and other replacements were on their way to their unit in Elbeuf, France, when they were attacked by German forces. Slovik intentionally avoided combat and walked away. He then joined up with a Canadian unit and did odd jobs, including cooking, for the next forty-five days. Slovik was returned to U.S. authorities on 4 October 1944 and reported back to the 109th Infantry three days later.

When questioned by his company commander, Captain (CPT) Ralph O. Grotte, about this absence, Slovik told Grotte that he was “too scared, too nervous” to serve with a rifle company and would desert again if ordered to fight (William B. Huie, The Execution of Private Slovik (1970) supra note 1, at page 127).

Slovik was then ordered to remain in the company area. Shortly thereafter, he returned to CPT Grotte and asked: “If I leave now, will it be desertion?” When Grotte said yes, Slovik left without his weapon. The next day, PVT Slovik surrendered to a nearby unit and handed a cook a signed, hand-printed note that said, in part: "I Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik confess to the Desertion of the United States Army. . . . I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out their again Id run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND ILL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THEIR," (Id. at 128).

After being returned to the 109th Infantry on 9 October, Slovik’s commander told him that the written note was damaging to his case and that he should take it back and destroy it. Slovik refused and was confined to the division stockade.

On 19 October, Slovik was charged with two specifications of desertion, in violation of the 58th Article of War. Both specifications alleged that he deserted “with intent to shirk hazardous duty and shirk important action, to wit: action against the enemy” on two different occasions: his forty-five day desertion from 25 August to 4 October 1944 and his one-day desertion from 8 to 9 October 1944.

On 26 October, Lieutenant Colonel Henry P. Sommer, the division judge advocate, offered Slovik a deal: if he would go into the line, that is, accept a combat assignment, he could escape court-martial. Slovik refused this offer and on 29 October his case was referred to trial by general court-martial.

On 11 November 1944, Slovik was tried for desertion. He pleaded not guilty and elected to remain silent. At the end of a two-hour trial, a nine-member panel found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. After Slovik was confined to the Army stockade in Paris, France, Sommer reviewed the record of trial. He recommended to Major General Norman “Dutch” Cota, the division commander, that the findings and sentence be approved. Cota approved the findings and sentence on 27 November.

From 1 December 1944 to 6 January 1945, Brigadier General E. C. McNeil, the senior Army lawyer in the European Theater, and lawyers on McNeil’s staff, reviewed Slovik’s case. McNeil wrote: "This is the first death sentence for desertion which has reached me for examination. It is probably the first of its kind in the American Army for over eighty years; there were none in World War I. In this case, the extreme penalty of death appears warranted. This soldier had performed no front-line duty. He deserted from his group of about fifteen when about to join the infantry company to which he had been assigned. His subsequent conduct shows a deliberate plan to secure trial and incarceration in a safe place. The sentence adjudged was more severe than he anticipated, but the imposition of a less severe sentence would only have accomplished the accused’s purpose in securing his incarceration and consequent freedom from the dangers which so many of our armed forces are required to face daily. His unfavorable civilian record indicates that he is not a worthy subject of clemency."

On 23 January 1945, General Eisenhower ordered Slovik’s execution by firing squad and directed that the shooting occur in the 109th’s “regimental area.” It should be noted that General Eisenhower did not simply decline to intervene in the Slovik case.

While 142 American Soldiers were executed for murder and/or rape during World War II, Slovik’s was the only execution for desertion in the face of the enemy.

In the years after Slovik’s death, his widow campaigned relentlessly for his records to be changed so that she could receive the proceeds of his $10,000 life insurance policy. While many were sympathetic, she and her supporters were unsuccessful. Today, most historians believe that Slovik might have escaped a firing squad had his timing been better. However, the 28th Infantry Division was engaged in bloody fighting in Huertgen Forest at the time of his trial, and the court-martial panel was in no mood for leniency. Additionally, when Eisenhower acted on Slovik’s case, the Battle of the Bulge was raging, and American forces were in serious trouble in the face of a German surprise offensive. Eisenhower likely saw that any value of leniency was outweighed by the view that maintaining discipline in the face of the enemy required that Slovik be executed.

Sources:

"Lore of the Corps - Shot by Firing Squad: The Trial and Execution of Pvt. Eddie Slovik" by Fred L. Borch III, The Army Lawyer May 2010

"The Execution of Private Eddie D. Slovik "by Dr. Jerold E. Brown, Combined Arms Battle Since 1939 (1992)

William Bradford Huie, "The Execution of Private Slovik" (1970)

1 file (169.3MB)